In a bid to attract more educators, this struggling Colorado school district was the first in a major metro area and the largest in the U.S. to make the switch.

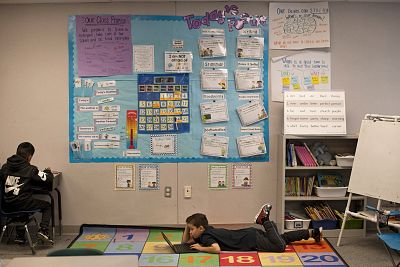

BRIGHTON, Colo. — Emma Cable, a junior at Eagle Ridge Academy in this working-class suburb north of Denver, spends her Mondays at volleyball practice and volunteering at a seeing-eye dog organization. Isabelle Jaramillo, a third-grader at Northeast Elementary, spends hers at the local Boys & Girls Club, while Angelica Gallegos, a sixth-grader at Vikan Middle, and her brother, Paul, a fourth-grader at Pennock Elementary, go with their mother to Barr Lake State Park.

Different grades, different activities and one thing in common: None of these students spend that day in class.

That's because their school district, 27J Schools in Adams County, Colorado — home to over 400,000 people — switched to a four-day school week at the start of this school year as part of an effort to recruit and retain better teachers. With 28 schools and about 18,000 students, it was the first district in a major metropolitan area and the largest school district in the United Statesto make the change, though it's been a growing trend among rural districts. Now, at the end of the experiment's first year, those affected gave it mixed reviews. While kids and teachers relished the regular long weekends, parents did not. Those with younger kids worried about child care, and those with older children worried about the unstructured free time.

But 27J Schools, whose teachers are the lowest paid in the Denver metro area despite numerous attempts to increase local taxes to fund raises, could still be model for other major urban and suburban districts facing funding and staffing challenges and looking for creative ways to attract quality educators. So far, the district — which has committed to the shortened schedule for at least another two school years — has seen increased, more promising teacher applicants and lower staff turnover.

"We weren't going to compete in the current system. You just can't be dead last in funding, last in starting teacher salaries, last in average teacher pay and expect you'll attract the best folks," 27J Schools Superintendent Dr. Chris Fiedler told NBC News in a recent interview.

Making a four-day week happen

In most states, including Colorado, minimum instructional requirements for public schools are governed by hours in the classroom, not days. As a result, resource-strapped districts like 27J can cut a day from the school week but still comply with requirements by extending the length of the other four school days.

Under their revised schedule, elementary school days were extended 40 minutes, while middle and high school schedules implemented longer, eight-hour days. Mondays were dropped.

"Unlike Friday, Monday is a day for kids and teachers to prepare for the week," Fiedler said.

Teachers in 27J Schools have mandatory professional development one Monday morning a month, while administrators have two. And the new schedule was rolled out with other initiatives administrators felt would help keep students connected to the classroom on their days off, including providing every student with a Chromebook laptop and the launch of a comprehensive digital curriculum.

To address daycare concerns for parents of young children, the district expanded its existing offerings to include an all-day option on Monday for $30 per day. 27J also enlisted the Shopneck Boys & Girls Club, in Brighton, to provide all-day Monday care for $20 for families that could afford it, and at no cost for those who could not.

Teachers and parents give it a grade

For single parents like Jessica Lore, who works full-time for a local sales company and has no family in the area, the four-day schedule was not a welcome change.

"I don't like it one bit, and I feel like the district didn't take seriously my worries about child care," she told NBC News as she picked up her three children from the Boys & Girls Club on a recent Monday.

If it weren't for that free service — Lore's kids receive a scholarship because she can't afford to pay — "I'd have been out of a job," she said.

Even for parents who can afford to have someone at home or who can enlist nearby family to help, the change wasn't universally well-received.

Brody Mathews, who has two children at Thimmig Elementary, wasn't thrilled about the elongated school days. And while child care wasn't an issue — he and his wife run a business out of their home — a work-related move to Golden, Colorado, will put his kids back in school for five days a week.

"I'll be relieved that they'll be back on a five-day schedule. It's what pretty much every human on earth works or goes to school for," he said.

On the other hand, students and teachers loved the shortened week.

Kids said they enjoyed having more time for play, rest and even homework, while high schoolers tended to pick up extra shifts at their part-time jobs, or volunteer to boost their college prospects.

Alec Alvarez, a third-grader at Thimmig Elementary, said he felt the new day was "kind of long" but that it was "worth it" so he could spend his Mondays at his grandmother's house "playing outside."

Zach Felker, a junior at Prairie View High, said he works up to 11 hours on Mondays at a nearby Buffalo Wild Wings to earn money to pay for college.

Teachers, meanwhile, cited having long weekends they can use to prep for the week while still having time for much-needed relaxation.

Ally Hyatt, a seventh-grade science teacher at Vikan Middle, had spent the first four years of her career in Denver Public Schools, and applied for a job last summer specifically in 27J Schools when she learned about their new schedule.

"It was attractive to me because I was essentially working that long of a day in DPS anyway. Here, I could just do it four days week," she said in an interview in the teachers' lounge at Vikan. "It's been amazing for my personal life, and I love that I have more time to actually plan lessons on Monday and get everything ready for the week."

Signs of success

That fondness among teachers has, so far, produced for 27J Schools what Fiedler hoped it would. Several school teacher positions that tended to attract just a handful of of applicants have netted more than 100, he said — including "harder vacancies" like special education and secondary math jobs.

He noted applicant quality has been higher, too, with more candidates possessing master's degrees and English as a Second Language certifications. The district's teacher turnover rate also declined from 21 percent last year to 13 percent this year.

The most meaningful data, however, aren't yet available. State test results and official graduation rates — which will help gauge the new schedule's impact on student performance — won't be ready until later in the fall.

And while the district says it's received a number of calls from other schools near and far inquiring about what worked and what didn't, no additional ones will make the change next year.

As a result, curious superintendents will be at the mercy of a thin and contradictory body of research on the effects of the four-day week. A 2015 study showedimproved academic performance for fourth- and fifth-grade students on the four-day week in rural Colorado districts. A 2017 study found that the four-day week had a detrimental effect on reading and math scores of third-through-eighth-graders in rural Oregon districts, with "minority, low-income, and special education students" being more adversely affected. And a 2018 study found that in rural Colorado districts on the four-day schedule, juvenile crime jumped 20 percent. (Brighton police said they haven't noticed any uptick in juvenile crime this school year).

Until more evidence is available, even proponents like Fiedler are warning that only districts similar to his own — ones looking to recruit and retain quality educators despite a funding crisis — should give it a go.

"If you have the money, you should pay your teachers," he said. "But for us, it's a significant differentiating factor that makes us really competitive."