One solution would be to work off an electoral-vote-per-population baseline.

WASHINGTON - It didn't get a tough draw for the tourney or get tied up in the admissions scandal, but the Electoral College is having a tough time. Just this week, the system for electing the president of the United States had its very existence called into question, when three different Democratic candidates called for abolishing it.For Democrats, the Electoral College has become a symbol of unfairness on the campaign trail this year. Twice in the last five presidential elections - including 2016 -the Democratic candidate won the popular vote, but lost the White House because of he or she couldn't win the states to get to the required 270 electoral votes.

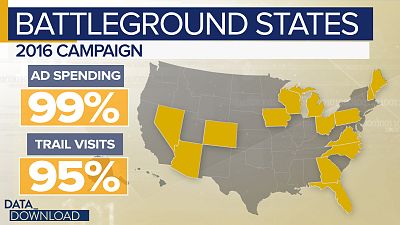

Leaving the sour grapes aside, however, the Democrats may have a few points when you look closer at the numbers. In theory, the Electoral College is designed to make presidential candidates campaign beyond big urban areas (where the most votes are) and all across the country, but in practice, it works a little differently.As every good civics student knows, the presidential election is actually 50 different state contests (plus the District of Columbia) where the candidates vie for electoral votes. Every state is apportioned electoral votes based upon the number of House members it has, plus its two senators. (The District gets three votes, as do the least populous states.)So, in theory, in a close election - like 2016 - every state, large and small, should matter. But, in reality, the current state of politics means only a select few states, battlegrounds, matter in a presidential election and the rest get little or no attention.For instance, in 2016, 99 percent of campaign ad spending was done in just 14 states, according to the America Goes to the Polls 2016 report.

The list - Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin - is certainly broad in some ways. It covers most of the various regions that make up the United States. But there is also a certain amount of randomness to the big 14.For instance, New Hampshire, a small New England state is there, but neighboring Vermont is not. Florida, one of the nation's biggest states, makes the cut, but not the other behemoths, California, New York and Texas.The reason, of course, is that beyond those 14, most of the other states are generally assumed to be in the Democratic or Republican column. So those other states, and their voters, are largely ignored. This is not what the Electoral College was designed to do. In some ways it is the opposite.And beyond those problems with the Electoral College, there is a fairness point that individual votes in some states count for more than those in other states.Take Wyoming.

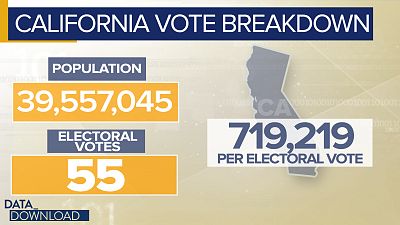

Yes, it only has three electoral votes, but it also only has about 577,000 people. That equals about one electoral vote for every 193,000 people.Now look at California.

The state has a whopping 55 electoral votes, but it also holds nearly 40 million people. That averages out to about one electoral vote for every 719,000 people. That means it takes more than three times as many people to get one electoral vote in California than it does in Wyoming.On its face, that doesn't seem fair. So what could be done?One solution would be to work off an electoral-vote-per-population baseline. What if we used Wyoming as that baseline and made every electoral vote equal to 193,000 people? There would be a few impacts.

First, there would be about 1699 electoral votes in play, using 2018 population estimates.And the new magic number would be 850, not 270.Under this scenario, the power of the biggest states would grow. California, Texas and Florida would all have a bigger share of the electoral vote total. To a lesser extent, the power would also grow for states such as New York, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina and Ohio.

But would it be enough to change an election? Maybe around the margins. Using the 2016 elections results, Hillary Clinton could have won the White House by just carrying Pennsylvania and Michigan along with the states she won. (In the current math she would have needed to win those two states plus Wisconsin.)But, of course, she didn't. Even a more representative electoral vote from California wouldn't have saved her.And that brings us back to the most basic element of the Electoral College. Love it or hate it. In the world of the 51 separate elections, the outcome in a few battleground states is always going to determine the winner.