Audiences think contemporary paintings should be easily understandable for anyone with eyes. But this is not the case.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

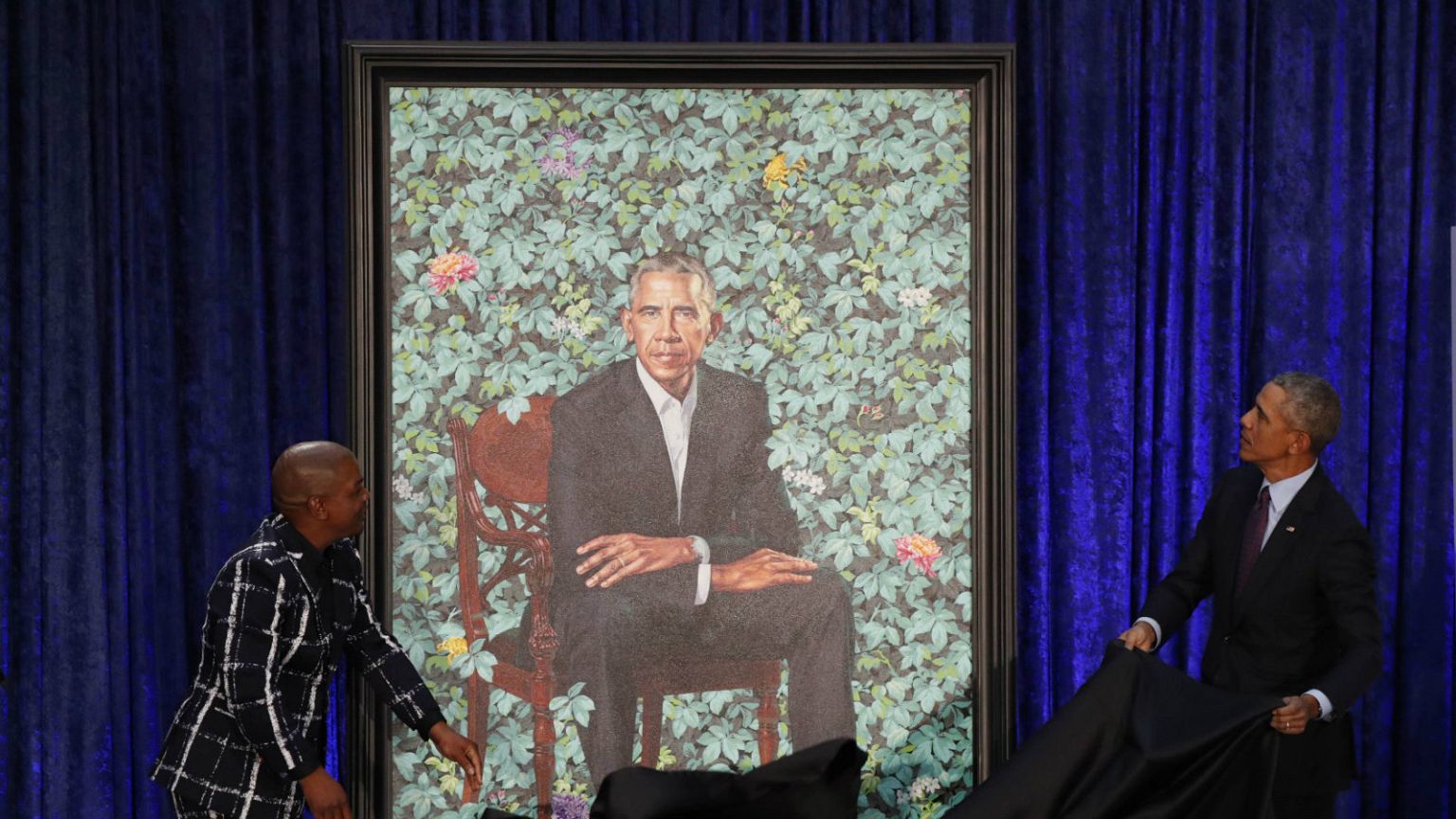

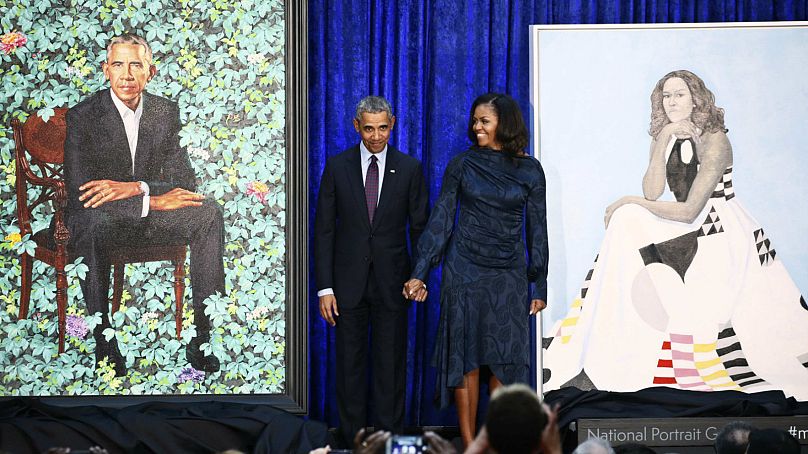

When former President Barack Obama chose artist Kehinde Wiley to paint his official portrait, everyone knew Wiley's interpretation was destined to stand out from the other paintings of previous presidents hanging in the National Portrait Gallery.

Sure enough, the unveiling of Obama’s portrait on February 12 was quickly met with controversy. Some people believed the painting too abstract, others found the background foliage confusing — and then there was the fact that Wiley had, in paintings completed in 2012, depicted black women holding the severed heads of white women after seemingly decapitating them. (Not making matters better, in an interview with Christopher Beam of New York Magazine, Wiley explained the work by offhandedly saying “It’s sort of a play on the ‘kill whitey’ thing.”)

Conservative news sites, not surprisingly, got out the pitchforks and torches. But more broadly, the widespread confusion over Wiley’s work points to a fundamental misconception held by American audiences who engage with art.

An audience that wants to read presidential portraits as a traditional representation of strength will be disappointed by someone like Wiley.

The general public tends to assume that contemporary paintings should be easily understandable for anyone with eyes to see them (and for more sophisticated audiences, for anyone who spends time and attention on the work). But this is not the case. Even if you are familiar with the moods, settings and styles of portraits you have previously seen, you are not necessarily equipped to understand Kehinde Wiley’s work. Wiley’s art — including the controversial beheading pieces — riff on the earlier portraits of by European Renaissance painters such as Caravaggio’s depiction of Judith Beheading Holofernes from circa 1599. Wiley also references the painting titled “Judith Slaying Holofernes” by the Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi.

An audience that wants to read presidential portraits as a simple, traditional representation and affirmation of strength, grace under pressure and valor will inevitably be disappointed or bewildered by someone like Wiley. This painter plays with his audience.

Indeed Wiley, as he conveyed to me last year, aims “to cross temporal boundaries and fuse contemporary urban street [culture] with the Western art historical canon.” His record of exhibitions further demonstrates this playfulness, as he has consistently engaged with the tradition of courtly painting, injecting commonplace urban figures into incongruous historical contexts. He works by that typical post-modern strategy of pastiche — mixing and matching styles and characters typically not viewed together to see whether unexpected meanings can arise.

Viewers who think they should be able to easily read and understand high-style portraiture but reject Wiley’s previous work also likely don’t understand how painting radically changed in the last century. After World War II, artistic production in general — and painting in particular —became much more complex. Artists began to pursue experimental, radical, unorthodox approaches to making art, to forming culture, to reimagining society. Wiley’s work comes out of this tradition of questioning and remixing his cultural inheritance.

So when Kehinde notes that some of his portraits were “a play on the ‘kill whitey’ thing,” he is conceding that there exists a cultural meme associated with black people venting their centuries-long frustration by slaying their oppressors. To depict what that might look like is an exploration of the social and political ramifications of an alternate reality. Similarly, his other portraits have explored the ramifications of his audiences seeing black people perform central roles in canonized artwork. His portraits of beheadings no more advocate for the murder of white women than the self-portrait of Van Gogh with a bandaged head promotes self-mutilation.

Contemporary painting is not simply pictorial; at times it is fiction, but at other times it is process.

The tradition of portraiture that we’ve inherited makes us believe that each painting is a window into a particular scene or reality. But contemporary painting is not simply pictorial; at times it is fiction, but at other times it is process, working through an idea. Contemporary painting is, essentially, more demanding. It asks you to get to know the history of the medium to more fully understand its possibilities and meanings. And sometimes painting plays with our expectations and desires — and even frustrates them.

It’s clear that some viewers will be frustrated by this presidential portrait. But if you are one of these people, you might ask yourself what you expected the portrait to look like. And why.

Seph Rodney has an English degree from LIU, Brooklyn, a studio art MFA from the University of California, Irvine, and a PhD in museum studies from Birkbeck College, University of London. He is an editor for the Hyperallergic blog, writing about contemporary art and related issues, and a current adjunct faculty member at Parsons School of Design.

The views expressed in opinion articles published by Euronews do not represent our editorial position. If you want to contribute to our View section, email ideas to: view@euronews.com.*

*