A German-based satirist has unveiled an online a project which draws attention to what some may consider inappropriate at Berlin's holocaust memorial

A German-based satirist has unveiled online a project designed to draw attention to what some may consider young people’s inappropriate behaviour when visiting Berlin’s holocaust memorial.

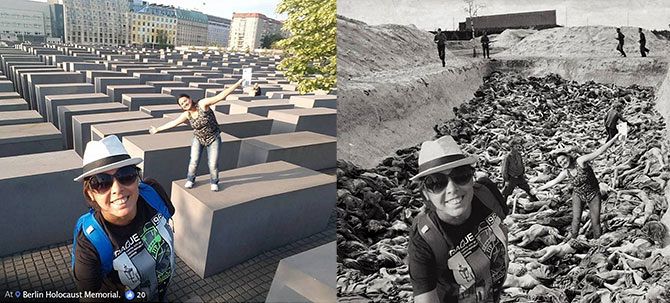

Entitled “Yolocaust” – a play on words of both the Nazi Holocaust and the millennial catchphrase You Only Live Once, or “YOLO” – Shahak Shapira, an Israeli satirist and author, lifted self-portrait images without permission from social media accounts including Facebook, Instagram, Tinder and Grindr and superimposed them onto archived images showing Nazi extermination camp victims.

The “selfie” images show people in various poses while visiting the memorial, located central Berlin near tourist destinations including the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate.

Shapira edited these onto the archived images in an attempt to link the Berlin memorial with the hallowed ground that are former Nazi concentration camps – none of which were located in Berlin.

The project appears to juxtapose some people’s arguably flippant behaviour at the memorial with the solemn significance of the monument, that Shapira argues, represents for many visitors gravestones for the millions of Jews buried in mass graves.

“No historical event compares to the Holocaust. It’s up to you how to behave at a memorial site that marks the death of 6 million people,” Shapira said on her website. “Yes, some people’s behaviour at the memorial site is indeed disrespectful. But the victims are dead, so they’re probably busy doing dead people’s stuff rather than caring about that.”

Shapira offers those whose images were used in the project to request their image be removed if they “suddenly regret having uploaded it to the internet.”

Berlin’s Holocaust Monument was designed by US architect Peter Eisenman.

At 19,000 square metres, it is almost double the size of a football pitch and is comprised of 2,711 concrete slabs.

Eisenman, a day before his monument’s unveiling in 2005, said in an interview with German newspaper Spiegel online , that while the monument honours the Jews murdered during the Second World War, he also wanted it to be a place where people can live in the present.

“I said all along that I wanted people to have a feeling of being in the present and an experience that they had never had before. And one that was different and slightly unsettling,” Eisenman said. “The world is too full of information and here is a place without information. That is what I wanted.”

The architect rejected in his interview the notion his monument should invoke German guilt over the past :

“When looking at Germans, I have never felt a sense that they are guilty. I have encountered anti-Semitism in the United States as well. Clearly the anti-Semitism in Germany in the 1930s went overboard and it was clearly a terrible moment in history. But how long does one feel guilty? Can we get over that? I always thought that this monument was about trying to get over this question of guilt. Whenever I come here, I arrive feeling like an American. But by the time I leave, I feel like a Jew. And why is that? Because Germans go out of their way — because I am a Jew — to make me feel good. And that makes me feel worse. I can’t deal with it. Stop making me feel good. If you are anti-Semitic, fine. If you don’t like me personally, fine. But deal with me as an individual, not as a Jew. I would hope that this memorial, in its absence of guilt-making, is part of the process of getting over that guilt. You cannot live with guilt. If Germany did, then the whole country would have to go to an analyst. I don’t know how else to say it.”

Sorry, aber #Yolocaust hat eher was mit Internetpranger denn Satire zu tun.

Man lese nur diesen Absatz der FAQ… pic.twitter.com/Kj6mxNg2ji— Miami Veisselmann (@Eisselmann) January 18, 2017

Reminding us again about that line between the sacred and profane: https://t.co/Ci9TSavK5z #yolocaust

— Maria Teutsch (@MariaTeutsch) January 19, 2017

The question of whether people are behaving respectfully when visiting Holocaust memorials, and indeed even concentration camps, has been a relatively new phenomenon and has sparked online debate.

In July 2016 visitors were reminded not to play Pokemon Go in on the grounds of the Auschwitz extermination camp.

During the particularly hot summer in August 2016 Auschwitz officials were branded as insensitive when showers that misted water to cool visiting tourists were installed at the site’s parking lot.

The question of tourists’ apparent abstraction from their surroundings when visiting holocaust memorials became the topic of a documentary by Sergei Loznitsa.

Entitled “Austerlitz”, and showed that the Venice and Toronto Film festivals, Loznitsa turned his lens to the thousands of people who every year visit the former Nazi camps.

Speaking to the New York Times, 2016 Loznitsa said the film explores his own existential crisis he felt when visiting the Buchenwald camp and contrasts it with the seeming indifference showed by others prompted in part by the rise in tourism to many former concentration camps.

“The people who came to these places 40 years ago came with a different purpose than people now,” Mr. Loznitsa said in a Skype conversation from Latvia, where he is shooting his next film. “Now, people don’t remember, and sometimes I think they don’t even understand where they are and what the places are about.”