A team of scientists at the University of Kentucky working with biblical scholars in Jerusalem have succeeded in revealing the contents of what looks like a lump of…

A team of scientists at the University of Kentucky working with biblical scholars in Jerusalem have succeeded in revealing the contents of what looks like a lump of charcoal.

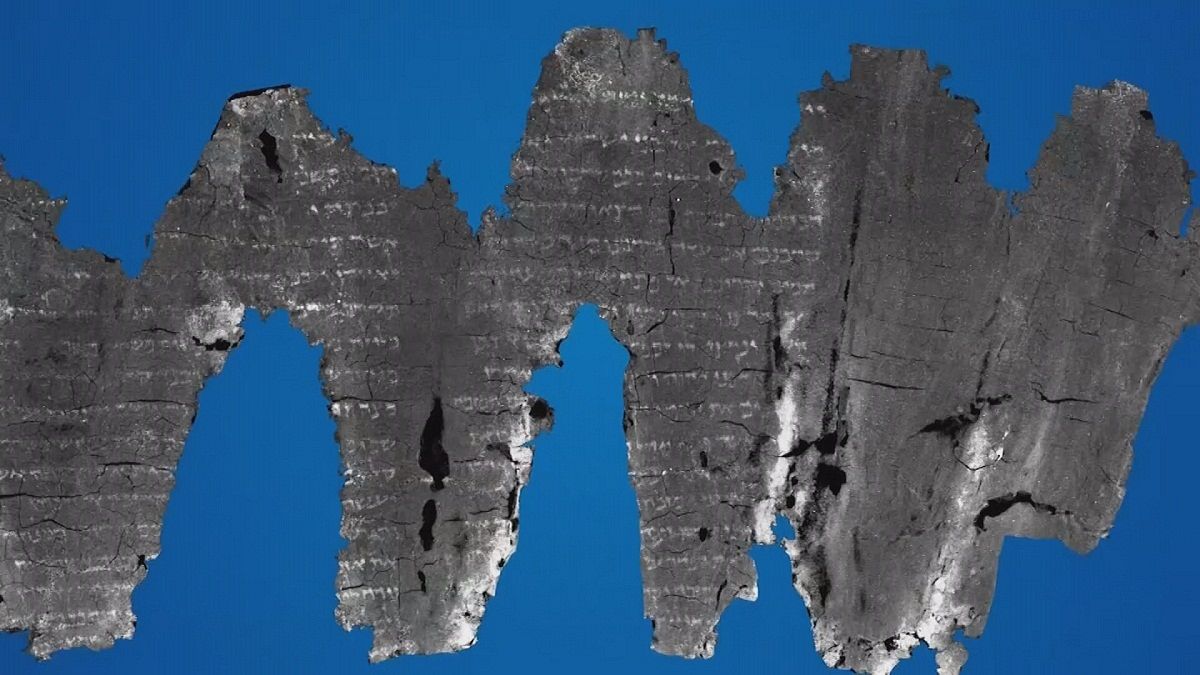

It is, in fact, a copy of the book of Leviticus – the earliest copy ever found of an Old Testament scripture.

Believed to have burnt in a blaze some 1.500 years ago, it is too brittle to open. But its contents have been revealed thanks to new imaging technology.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/22/science/ancient-sea-scrolls-bible.html?_r=0

“This piece of charcoal was actually once a beautiful scroll with writing on it. It burnt down and is therefore illegible. What we did with the virtual unrolling is to go into the insides of this chunk, and to separate it into different layers, and to find the layer that had the best remains of writing and to unroll it,” explains Pnina Shor, head of the “Dead Sea Scrolls” http://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/learn-about-the-scrolls/discovery-and-publication?locale=en_US project at the Israel Antiquities Authority in Jerusalem.

The discovery was made using what’s called “virtual unwrapping”, a 3D digital analysis of an X-ray scan.

https://youtu.be/VfNl7z-vFl4

It’s the first time researchers have been able to read the text of an ancient scroll without having to physically open it.

“When I saw this box with something black, I never imagined it would be possible to do anything with it,” says Elena Libman, head of laboratory at the Dead Sea Scrolls project.

Virtual unwrapping begins with a three dimensional scan of the damaged manuscript, layer by layer – a process called segmentation.

The software moves through the scroll, image by image, tracing the shape of a single scroll wrap and producing a 3D model. Next, the ink is extracted in a process called texturing. Using the 3D shape generated by segmentation, the software passes through the scroll again, this time looking for very bright pixels, that indicate regions of dense material – in this case, inks made with iron or lead.

The textured 3D surface is then digitally flattened so the text can be more easily read. The software works on one small section of the scroll at a time. The sections are then merged together, creating a consolidated image that shadows the full text.

In ancient times, many different versions of the Hebrew Bible circulated. The Dead Sea Scrolls, dating back to as early as the 3rd century BC, featured versions of the text that are radically different to today’s. The discovery holds great significance for scholars’ understanding of the Bible and other ancient texts.

“What this technology is going to do is it’s going to open new horizons in scientific research in the sense that we will no longer need to necessarily destroy the artefact by unrolling it or by intervening, because we will be able to look into the insides of any kind of object, hopefully, without needing to do any kind of intervention,” says Pnina Shor.

The passages discovered offer the first physical evidence of what has long been believed: that the version of the Hebrew Bible used today could stretch back as far as 2,000 years.