“Center stage: Opéra National de Paris” was produced by the T Brand Studio international department and did not involve the International New York Times reporting or editorial departments. It was sponsored by Rolex. Text by Nick Hammond.

Looking to the future: How do opera houses, festivals and orchestras maintain tradition while moving their art forms forward, build and educate new audiences, and take advantage of technical innovations in communications and stagecraft?

Leaders’ vision

Plans for new works in opera and dance

In the vast rehearsal and office spaces behind the Bastille Opera house in Paris, there is a discernible sense of new energy and drive. Dancers grab lunch between rehearsals, a top opera director takes a coffee break in one of the outside spaces, the dedicated staff (many of whom work throughout the day and well into the night) scurry through the corridors. Everyone seems to share excitement about a place that is undergoing many changes.

On the huge facade of the Bastille Opera are emblazoned the words: ‘‘Verdi or Schoenberg, why choose between them?’’ It is a bold statement of intent from the new regime at the Opéra National de Paris, led by Stéphane Lissner, for it forces audiences to confront the safety of their operagoing habits and to consider experiencing not only the traditional but also a more modern repertoire.

Judging from the huge creative and box-office success of the opera that opened the 2015-16 season, Schoenberg’s ‘‘Moses und Aron,’’ spectators are embracing this challenge with relish. Lissner moved from the role of general manager and artistic director at La Scala in Milan to become director of the Paris Opera in August 2014, and, together with Benjamin Millepied, who became director of dance in November 2014, they have a clear vision for the future.

Lissner, who started acting at the age of 15 and founded his own company at 18, is very much a man of the theater. He believes passionately that opera should never revolve around the voice alone.

‘‘Opera for me is a combination of theater and music,’’ he explains, ‘‘making the audience reflect upon many subjects that touch people.’’

Stéphane Lissner, director of the Paris Opera

Credit: Elisa Haberer / Opéra National de Paris

His own musical education, he says, is unusual, since his fascination with 20th-century theater led him to engage with modern composers like Pierre Boulez and to study works that were inspired by dramas, such as Alban Berg’s two operas, ‘‘Wozzeck’’ and ‘‘Lulu.’’ Only later did he grow to appreciate and love repertoire from earlier eras. This might explain why he makes no value judgment when speaking of 12-tone music or operatic works that form part of the core repertoire. He refuses to call those audiences who prefer the classics ‘‘conservative,’’ however, saying that it is just a question of taste.

He insists that he never seeks to commission productions that set out deliberately to shock but rather chooses directors whose previous works have marked him profoundly. In the case of the Italian director Romeo Castellucci, for example, whose production of ‘‘Moses und Aron’’ launched the current season in such a memorable way, Lissner describes watching Castellucci’s productions of Gluck’s ‘‘Orfeo ed Euridice’’ and Wagner’s ‘‘Parsifal’’ as important moments in his life.

Lissner appreciates especially what he calls the ‘‘Cartesian’’ approach of those at the Paris Opera toward planning and organization, and above all the great history of the place, which gives them the savoir faire to stage both opera and ballet in the same institution.

‘‘No other major company has two different locations in the city,’’ he says, referring to Bastille and the 19th-century Palais Garnier, ‘‘nor is there any other place that offers so many new productions and different works each season.’’

As with so many European arts institutions, public financing of the Paris Opera has diminished, dropping in six years from 58 percent to 47 percent of the budget.

Lissner’s response: ‘‘Others believe that you need to produce less in order to spend less. My perception is the opposite: It is important to produce more in order to obtain more financing and private sponsorship.’’ Savings are being made by mounting co-productions, such as the forthcoming collaboration with the Metropolitan Opera of New York of Saint-Saëns’s ‘‘Samson et Dalila.’’

A new program for patrons, the Cercle Berlioz, offers the opportunity to dive into the heart of the creation of works in the Paris Opera’s Berlioz series. All through the staging process, the Cercle Berlioz invites its donors backstage, along with the artists, to discover the operas from behind the curtain.

One of the most exciting ventures into new music over the next few seasons will be the commissioning by Lissner and the Paris Opera of a series of operas on the theme of French literature.

The first of these, by the Italian composer Luca Francesconi, will be on a fascinating character created by Honoré de Balzac, Vautrin, and is due to be premiered in the 2016-17 season. In the following two seasons, there will be two more operas, one inspired by Paul Claudel’s ‘‘Le Soulier de Satin’’ and the other by Jean Racine’s ‘‘Bérénice.’’ Lissner emphasizes that new operas in the French language are an important component of his blueprint for the future of the Paris Opera.

For his part, Benjamin Millepied shares Lissner’s strong vision for the future. ‘‘The excitement of the opera is helping the ballet and vice versa. We are certainly a stronger force together,’’ he says. Ballet in the modern age has become separate from music and the visual arts, he asserts, and needs to be reconnected with the golden age of collaboration, when all aspects of performance maintained the highest of standards.

Benjamin Millepied, director of dance at the Paris Opera

Credit: Julien Benhamou / Opéra National de Paris

‘‘I want the ballet to be on the level of the scores,’’ he insists. To achieve this, he believes that working closely with conductors will lead to a more integrated sense of collaboration. Although no names have been announced yet, he says that starting with the 2017-18 season, major international conductors will be coming to Paris especially to conduct for the ballet.

‘‘Ballet is and should be a joyful, romantic, intellectual experience,’’ he says. ‘‘I feel I have an important mission to succeed, to renourish an art form that I love, and the Paris Opera Ballet is one of the best platforms in the world to do what I do.’’

Rendezvous: ‘La Damnation de Faust’

A fairy tale and a voyage of the mind

Alvis Hermanis is a busy man. With 10 projects running concurrently, and knowing exactly what he will be doing until 2019, the Latvian director is very much in demand. On the operatic stage, he has already worked with the world’s top conductors and singers, and his new production of Hector Berlioz’s ‘‘La Damnation de Faust’’ (as both director and designer) at the Paris Opera, starting Dec, 8, is no different, with the house’s musical director, Philippe Jordan, conducting three of the great singers of the day: Jonas Kaufmann (in the role of Faust), Bryn Terfel (Méphistophélès) and Sophie Koch (Marguerite).

When asked in what ways he finds directing opera different from directing theater — since 1997, he has been artistic director of the New Riga Theater, in the Latvian capital — Hermanis ponders carefully before replying: ‘‘Trends in European theater in the last 30 years have tended to have a mentality of destruction. Opera, on the other hand, allows you to focus on harmony, giving us a chance to put things back together.’’

Growing up in the Soviet Union, he absorbed the Russian theatrical tradition of psychological realism. ‘‘But for opera,’’ he says, ‘‘it is hard to be realistically precise, because often there is already an aesthetic contradiction from the composer’s side, where music written in one century tells a story from another century, such as in Verdi’s ‘Il Trovatore,’ which uses 19th-century ideas to depict the 15th century.’’

Hermanis is both modest and pragmatic in recognizing the difficulty of pleasing audiences. ‘‘Music is such an intimate and personal thing, and yet the director is forcing the audience to look at his or her vision and images. How can you possibly make everybody enjoy and appreciate that vision? I am starting to accept that this is ‘mission impossible.’’’

Unlike other directors, such as Robert Wilson, who have a very distinctive style, Hermanis insists: ‘‘My style is that I have no style. You cannot open every door with the same key.’’ He explains that he enjoys changing his approach in order to match different scenarios.

In the case of ‘‘The Damnation of Faust,’’ Hermanis is well aware of the pressures of presenting his ideas about a French work before a French audience, even though, as the director of the Paris Opera, Stéphane Lissner, points out, Berlioz’s music has tended to be more fully appreciated in the English-speaking musical world than in the land of the composer’s birth.

Certainly, the opera does not lend itself to an overly realistic depiction. Berlioz called it a ‘‘dramatic legend’’ rather than an opera. Hermanis himself prefers to call it a fairy tale, and he explains that as such it is impossible to conceive of the work in historical terms.

Alvis Hermanis staged ‘‘La Damnation de Faust’’

Credit: Janis Deinats / The New Riga Theatre

That the action leaps frequently from location to location might explain why the first performances on the stage failed to gain critical acclaim in Paris in 1846. Luckily, modern technology has enabled the work to be depicted more effectively on a visual level, and Hermanis has teamed up with the video artist Katrina Neiburga for this production.

Hermanis’s conception of ‘‘Faust’’ led him to visualize the action as a voyage within the mind of the person he calls ‘‘the Faust of the 21st century,’’ the scientist Stephen Hawking.

Hermanis has nothing but praise for the Bastille Opera. He points out that the ample backstage space enables the whole set to be constructed before rehearsals even start, and he has been allowed four years of planning for his ideas about the piece to mature.

Philippe Jordan has committed himself to a cycle of Berlioz works over the next five seasons, with highlights including a concert performance of ‘‘Béatrice et Bénédict,’’ a production by Terry Gilliam of ‘‘Benvenuto Cellini’’ and a major production of the monumental ‘‘Les Troyens’’ in 2019.

The art of the tenor: Jonas Kaufmann

In Faust, a musically wide-ranging role

Jonas Kaufmann is possibly the most sought-after tenor in the world at the moment, selling out opera houses and concert halls well in advance, and it is easy to see why. He possesses an impressive vocal range (from high tenor down to deeper baritone) and has the versatility to perform at the highest level in a wide variety of repertoires, encompassing lighter lyric tenor roles, the great roles of the Italian, French and German 19th-century operatic canon and, in recent years, even singing a number of the much heavier Wagner parts. Those who were lucky enough to see his Parsifal or Siegmund (in ‘‘Die Walküre’’) at the Metropolitan Opera in New York will not forget his performances in a hurry. It is therefore no surprise when he cites Plácido Domingo as one of his earliest influences, because the Spanish tenor/baritone is one of the very few singers to have similar versatility and flexibility.

Kaufmann is a familiar face in Paris. He has performed regularly at both the Opera Garnier and the Bastille Opera, where he is returning to sing the title role in Berlioz’s ‘‘La Damnation de Faust,’’ opposite Bryn Terfel as Méphistophélès and Sophie Koch as Marguerite (two singers that he knows well), during the month of December.

He loves especially the sharp contrast between the Bastille and the Garnier. ‘‘It is wonderful to have two very different opera houses for different repertoires,’’ he says. ‘‘The shape of the Bastille stage is strange to some because it is so wide, but the acoustics are very good and they help the singers to have the audience at much closer range than is the case in many more traditional theaters.’’

Although he has sung the part of Faust in a number of operatic and concert performances, it has been a decade since he last performed the role, and he is happy to revisit it. When asked whether his interpretation of Faust has changed since he first played the part in Brussels in 2002, he is emphatic that he adds to the character every time he rediscovers it.

Also, the fact that his voice has developed in the last few years with the new roles that he has sung means that some musical phrases that used to challenge his voice now come much more easily.

Vocally the part is, he says, similar to many French repertory roles: ‘‘They never want to stay in one direction. The music follows the emotions. For Faust, at one moment there is a high lyric side which then moves to a dramatic range, with strong emotions involved. Later, after he has encountered Méphistophélès, he is almost a Heldenbaritone, with some low notes. It’s a big mix but it makes sense, since it follows the whole gamut of feelings that Faust is going through.’’

Jonas Kaufmann sings the role of Faust

Credit: Julian Hargreaves

Before the premiere of the Berlioz opera on Dec. 8, Jonas Kaufmann will be singing in the ‘‘pre-premiere’’ dress-rehearsal showing on Dec. 5, which is open to spectators who are under the age of 28 and who pay only 10 euros (or about $11) for their ticket, and he is excited by the prospect.

‘‘It is a great idea,’’ he says, ‘‘as it attracts a younger audience to the opera. The experience is very different, as sometimes the audience giggles where you wouldn’t expect it, but it is always interesting to see their reaction. ‘La Damnation de Faust’ is a fresh and young piece, and I think that a young audience will respond well to it.’’

Having recently sung in the Royal Albert Hall in London at the ‘‘Last Night of the Proms,’’ where the audience is always very vocal and raucous, Kaufmann jokes that he is now ready to face any reaction when

on stage.

Kaufmann is always preparing new parts, and, in addition to returning to the Bastille in a year’s time to sing the title role in Offenbach’s ‘‘Tales of Hoffmann,’’ he is about to sing in Wagner’s ‘‘Die Meistersinger’’ in Munich and in Verdi’s ‘‘Otello’’ in London, and is also learning some new Wagner roles.

As for the future of opera and classical music, Jonas Kaufmann is optimistic. Even if there are ups and downs in the music world, he says, many people, like him, cannot live without it: ‘‘Of course the financial cuts of the past few years have had an effect, but one of the best distractions from such crises is music. People forget their sorrows, are able to dream and travel into another world.’’

The art of the bass-baritone: Bryn Terfel

A dream role in a rare Paris appearance

The Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel is about to make a rare appearance at the Opéra National de Paris, singing the crucial role of Méphistophélès opposite Jonas Kaufmann’s Faust in the forthcoming new production of Berlioz’s ‘‘La Damnation de Faust.’’

Ever since Terfel shot to prominence at the Cardiff Singer of the World competition in 1989 — dubbed the ‘‘Battle of the Baritones,’’ with the Russian singer Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who won the overall competition, and Terfel, who took the Lieder prize — he has been a much sought-after singer worldwide, perhaps most celebrated for his definitive interpretation of Wotan in the Wagner Ring Cycle at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and at the Royal Opera House in London.

Even though he has sung on the Bastille Opera stage in only two previous productions, he has very fond memories of the place, perhaps most particularly because he was able to make his debut in Mozart’s ‘‘Don Giovanni’’ in 1999, performing onstage for the first time with a singer he calls ‘‘iconic,’’ José van Dam.

‘‘He is a performer that I had listened to countless times as a student,’’ Terfel explains, ‘‘and I had placed him squarely on a pedestal. He did not disappoint!’’

Nor has Bryn Terfel forgotten the fervor of the Parisian audiences. He describes them as ‘‘incredibly passionate and supportive of their singers, even in a production that they maybe had issues with. They certainly declared their thoughts with authority!’’

As to the experience of singing on the huge Bastille stage, Terfel waxes lyrical: ‘‘I loved singing on that stage. It is an expansive space that to me has an impressive dignity.’’ He is mindful of coming to Paris just after the terrible events of Nov. 13, but says that at moments like these, art and entertainment become even more crucial for a culture.

Unlike Kaufmann, who has sung in other productions of ‘‘La Damnation de Faust,’’ this will be the first staged production of the work in which Terfel has performed (he sang the role in a concert with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in March).

He is eager to discover how the full production will develop: ‘‘The storytelling will certainly be an important facet. The music is self-explanatory, and scenes will flow from one to another with the dancing, the choral singing, duets, trios, arias — but it is, without a doubt, an extreme challenge to stage.’’

As for the role of Méphistophélès, Terfel calls it ‘‘a bass-baritone’s dream portrayal.’’ Having sung in many versions of the Faust story, including those by Gounod, Boito and Schumann (the latter in a recorded performance under the great conductor Claudio Abbado), Terfel is eager to add Berlioz’s tale to his stage experiences.

Bryn Terfel returns as Méphistophélès in a rare appearance at the Paris Opera

Credit: Rudy Amisano / Teatro alla Scala

One of Terfel’s most endearing characteristics is his enthusiasm for the artistic excellence of his fellow singers, an excellence that he matches in his own performances. He notes that he is especially thrilled to have the chance to sing again alongside Jonas Kaufmann.

‘‘Jonas is, in a nutshell, an incredible artist,’’ says Terfel. ‘‘On top of that he is adorable and, dare I say it, a quite fabulously perfect singer! How he repeats such high-quality performances day in, day out is for me totally inexplicable. What is his secret, what is that formula? Most singers, as famously mentioned by Hans Hotter, sing their best performances in the music room at home.’’ (Hotter, a prominent German bass-baritone, died in 2003 at the age of 94.)

The answer, says Terfel, ‘‘of course, is hard work and dedication, and he has it in abundance. You only have to listen to his style and interpretation, listen to his command of different languages. And on the stage he is like a great ship with the wind in its sails. Long may it continue.’’

Terfel calls it a privilege to have the chance to return to Paris and to sing Berlioz under the musical direction of Philippe Jordan, whom he sees as well suited to conduct such an iconic work. With such an array of world-class performers involved with the production, he modestly exclaims: ‘‘I only hope that I can reach the dizzy heights of all these musicians’ qualities.’’

Given the wealth of his own musical experience and the international acclaim his performances have received, there is little doubt that the Parisian audiences will be clamoring for his return very soon.

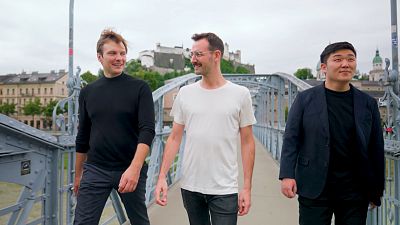

Rehearsals at the Paris Opera for ‘‘La Damnation de Faust,’’ which opens Dec. 8. From left to right, Sophie Koch (Marguerite), Jonas Kaufmann (Faust) and Bryn Terfel (Méphistophélès)

Credit: Felipe Sanguinetti / Opéra National de Paris

Next generation

Encouraging young people to become ‘regulars’

One of the great challenges facing any arts organization is to find ways of attracting new and younger audiences.

According to Stéphane Lissner, director of the Opéra National de Paris, the average age of those attending the opera is 46, and 42 for those going to the ballet.

Since Sept. 1, various initiatives have been set up to cater to those young people for whom the cost of attending the opera would normally be beyond their means. Tickets for those under 28 years old are being sold at 10 euros, or just under $11, for the ‘‘pre-premieres’’ at dress rehearsals of eight operas and five ballets, and the response has already been strong, with productions sold out within 20 minutes of going online, after much interest on social media.

Most tellingly, for the first two productions for which the offer was made, 56 percent of those who bought low-price tickets had never been to an opera or ballet before at Bastille or the Palais Garnier.

Lissner says he believes strongly that there are measures in place to encourage these spectators to return: ‘‘The Paris Opera has other loyalty initiatives, not to become subscribers but regulars. We are also beginning to find out what kinds of music such new audiences hope to hear.’’

Various educational programs are already being brought to schools in the Paris area, especially for socially disadvantaged kids, but the opportunity is also being offered to schoolchildren to come to the Paris Opera on Wednesdays to work with the musicians and to see the workings of an opera house.

Through the new 3e Scène, or Third Stage, digital platform, creative artists are making short films on different themes related to the Paris Opera (such as architecture, voice and theater).

The artistic director of 3e Scène, Dimitri Chamblas, explains: ‘‘The 3e Scène represents another public space for the opera, following its two other public spaces, Bastille and Palais Garnier. The directors of opera and dance, Stéphane Lissner and Benjamin Millepied, wanted to explore how the Paris Opera could exist in the public space of the Internet. Rather than feeling the need to post short updates continuously, we decided that creativity was key, and the wager we took was to create something that resembles us, where the world could observe us, and where we could open our arms to all generations.’’

The digital initiatives, says Millepied, open up opera and ballet to a worldwide and younger audience. ‘‘It helps make ballet cool to a wide range of people,’’ he says.

Rolex culture partners: Opéra National de Paris

Starting Dec. 24, the Euronews ‘‘Musica’’ program will dedicate a broadcast to the Paris Opera’s ‘‘La Damnation de Faust’’ with Jonas Kaufmann as Faust and Bryn Terfel as Méphistophélès. Interviews with the German tenor and the Welsh bass-baritone will also be included in the report. Go to euronews.com/programs/musica.

Medici.tv provides free streaming of prestigious classical music concerts, operas and ballets, and access to an extensive video library. Go to medici.tv/#/playlist-opera-national-de-paris to watch great performances by Jonas Kaufmann, Natalie Dessay, Rudolf Nureyev, Joyce DiDonato, Susan Graham and many others at the Paris Opera.

A rich guide to the world of opera, the website Opera Online analyzes significant operas in their musical and historical context. Go to tinyurl.com/OO-DFaust for a detailed look at Berlioz’s ‘‘La Damnation de Faust’’ and to tinyurl.com/00-Lissner for video of an in-depth interview (in French) with Stéphane Lissner, director of the Paris Opera.