Breathing new life into Europe's deserted rural villages by taking in refugees: that's the fight that Riace, in southern Italy, has been waging for more than 15 years. But are things there really goin

It was a special day in Riace, a small village in Calabria, in southern Italy, as residents recently celebrated Saints Cosmas and Damian — doctors of the poor, patrons of Riace and of gypsies.

There was also a special guest joining the mayor to open the ceremony: 9-year-old Even, who had arrived from Ethiopia just three days before.

“Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian came from Syria. Today Syria is in many ways at the centre of the world’s problems; there’s an exodus that’s unprecedented in the history of mankind. Today, in Riace, we have a child as a symbol of hope, of a new life, to which all humans are entitled,” Domenico Lucano, Mayor of Riace, said during the celebrations.

The little boy had not seen his mother, Haregu, since she arrived in Riace four years ago, after fleeing from Eritrea. Haregu had just been reunited with her son when euronews met her in the glassworks where she earns a living. As a political refugee, she was able to get her son to Riace, under family reunification laws.

“It was hard to take the children out of my country,” Haregu said. “My sister took my son and she left to Ethiopia. She fled Eritrea like me, with the children. And I sent her money for my son. If I hadn’t had this job, nothing would have happened. This job helped me a lot. “

Haregu works in one of the craft workshops set up by the NGO Citta Futura (“City of the Future”) which co-manages a protection program for refugees and asylum seekers funded by the interior ministry. Through it, refugees are offered housing, financial aid, Italian courses and other training dispensed by locals.

Reviving hope

Riace is widely described in the media as the village where migrants are welcome. It all started in 1998, when a boatload of 300 Kurdish refugees arrived on the local shores.

One man set up Citta Futura with the ambition to both help the refugees and revive what was then a dying rural village. That man later became mayor: Domenico Lucano, whom everyone here affectionately calls Mimmo.

Taking in refugees allowed the village to preserve basic public services such as schools, but also shops and businesses that had virtually disappeared, Lucano said: “The arrival of these people fueled dynamics that created hope. For the people who arrived, but also for the people here.”

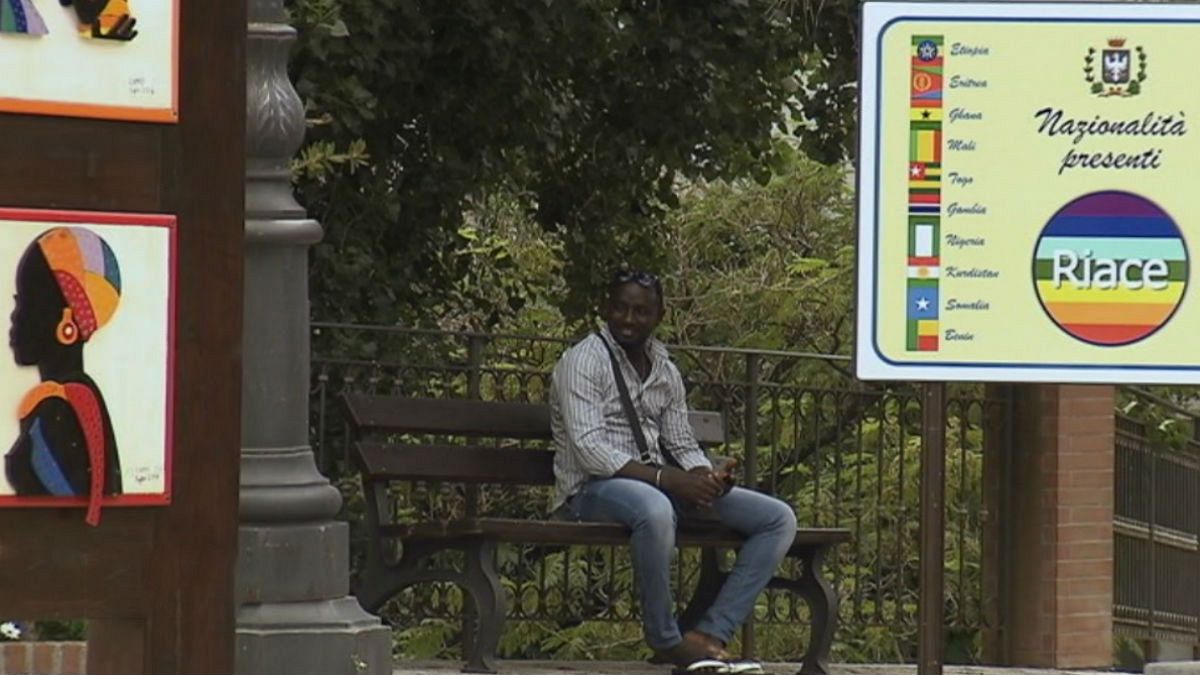

Riace’s population has since more than tripled to 2,800, among whom are 400 immigrants of more than 20 nationalities. It’s a fortunate turn of events, say longtime residents whose own path is often one of exile.

Francesco Capece, for example, only returns to Riace on holidays: “I left to find work; in 1996, to Turin. Because here there’s nothing left; you can’t do anything, you can’t start a family, there’s no future. There was a time when there was a lot of work, but now there’s nothing. Only immigrants, really. And thanks to them the village has somewhat come to life again.”

At a cafe, longtime resident Leonardo Squillace said: “The village was repopulated! All these people came! We became friends; they send them here, and we’re very happy about that!”

But the new energy instilled in the village remains fragile. Few of the families in Riace settle for the long haul. This local school now has 11 pupils, including six non-Italians.

“Without foreign children, this school would have remained closed,” said teacher Maria Grazia Mittica. “But the number keeps changing. Because foreign children come and go.”

Daniel Yaboah arrived in Riace from Ghana six years ago. He’s in charge of garbage collection in the village. He says he hopes to stay as long as possible in the village that welcomed him and his family.

“This town means a lot to me. The people here are very good people. They are kind to everybody, There is no discrimination. So I’m very happy here,” he said.

His two children were born in Riace. He called them Cosimo and Domenico, in honor respectively of Saint Cosmas and of the mayor of Riace: “I want to use this (story) as an example all over the world, all over the European countries. That if they make up their mind to help the foreigners… we too are ready to help.”

Empty homes

Bahram landed in Italy almost 20 years ago, on the boat of Kurdish refugees that changed the face of Riace. He’s since secured Italian citizenship and has become the oldest foreign resident in the village.

He even started his own business — until the economic crisis forced him back to temp jobs in construction. He feels at home in Riace, but says times are rough for everyone.

“All of Italy was hit by the crisis. And Calabria is one of the regions that’s been most affected, because it’s not an industrial area. The past two-three years, there’s been little work. So for five or six months of the year, I’ve been working in a program of the association Citta Futura. Otherwise, if we find work outside we go, and if we don’t, we stay at home.”

In the narrow streets of Riace, a lot of homes are empty. For many, the village is just a port of call.

Agali, who came from Mali, no longer has any financial support, apart from some generous villagers. He can’t find any work. So he hopes to try his luck elsewhere: “I have to get my residence permit, and then I’ll try to sell something, I don’t know… maybe my clothes… Or I’ll try to get someone to help me pay for a ticket to go somewhere. “

We hear the same distress from the asylum seekers we meet in the lower part of the village. Even with the support of associations, they feel stuck: Riace is not really the utopia it’s said to be.

“It’s hard to live well here,” said one asylum seeker, who asked not to be identified. “We’re not really at ease. And those of us who don’t have the right documents get treated very badly. For example, I worked for three months somewhere and I still haven’t been paid. There are times when you go home and you’re ready to shed tears. Yes, you feel like crying. Because things are really bad. “