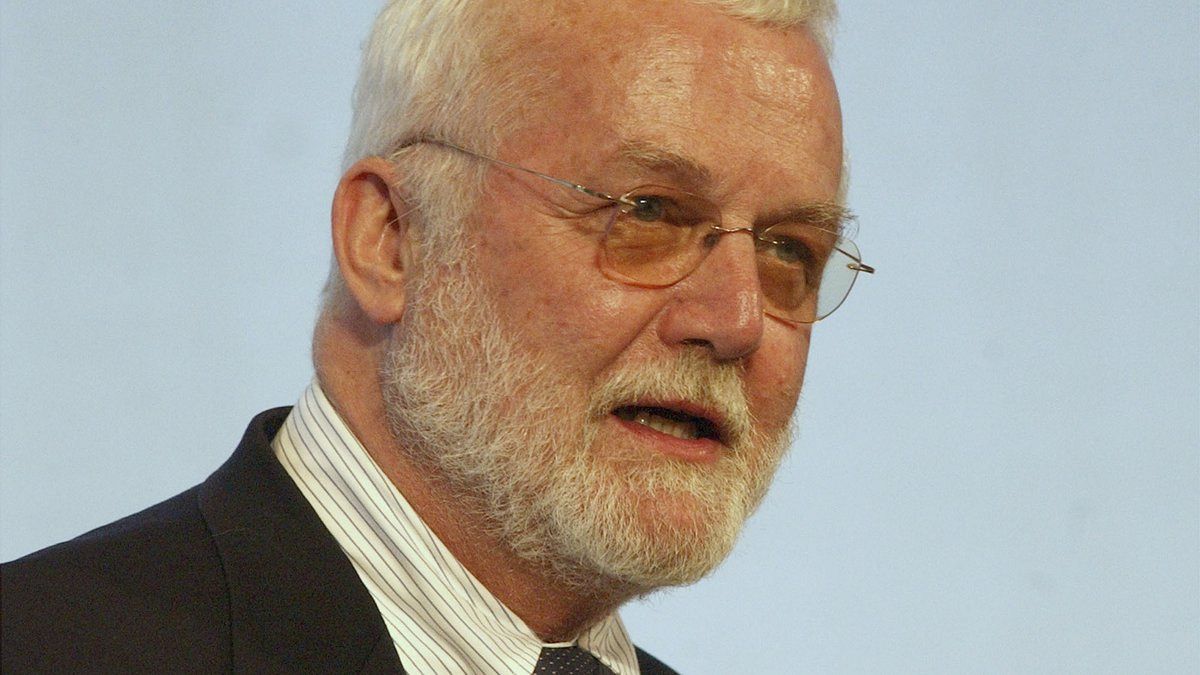

American novelist Russell Banks, a major figure in contemporary literature, known for his portraits of working-class hardship, poverty and racial issues, died aged 82.

American novelist Russell Banks, a major figure in contemporary literature, known for his portraits of working-class hardship, poverty and racial issues, died on Saturday 7 January at the age of 82.

The professor emeritus at Princeton University and author of ‘Affliction’, ‘The Sweet Hereafter’ and ‘Cloudsplitter’ passed away peacefully at his home in upstate New York," writer Joyce Carol Oates announced Sunday morning on Twitter.

“I loved Russell & loved his tremendous talent & magnanimous heart,” Oates wrote. “'Cloudsplitter'” -- his masterpiece, but all his work is exceptional.”

Banks’ editor, Dan Halpern, told The Associated Press that the author was being treated for cancer.

Born on 28 March 1940 in Newton, Massachusetts, and raised in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Banks was a self-styled heir to such 19th century writers as Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman, aspiring to high art and a deep grasp of the country’s spirit.

He was a plumber’s son who wrote often about working-class families - whether those who died trying to break out, caught up in a “kind of madness” that the past can be erased, or those like himself who got away and survived and asked “Why me, Lord?”

He was inspired by the writing of Jack Kerouac, another son of Massachusetts, whose novel ‘On The Road’ had a huge impact on the Banks. His books often told of absent and otherwise failing fathers and Banks’ own father, Earl Banks, was an alcoholic whom the author says beat him as a child and left him with a permanently damaged left eye.

His critical breakthrough was ‘Continental Drift,’ published in 1985, about an oil burner repairman who flees from his native New Hampshire and goes into business with his wealthy brother in Florida, only to learn his brother’s life was as hollow as his own.

‘Cloudsplitter’ was his most ambitious novel, a 750-page narrative on abolitionist John Brown, released in 1998. The story long precedes Banks’ lifetime, but the inspiration was literally close to home. Banks lived near Brown’s burial ground in North Elba, New York, and he would pass by often enough that Brown “became a kind of ghostly presence,” the author told the AP in 1998.

Banks was a Pulitzer finalist for ‘Cloudsplitter’ in 1999 and had been one 13 years earlier for ‘Continental Drift.’ His other honors included the Anisfeld-Book Award for ‘Cloudsplitter’ and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

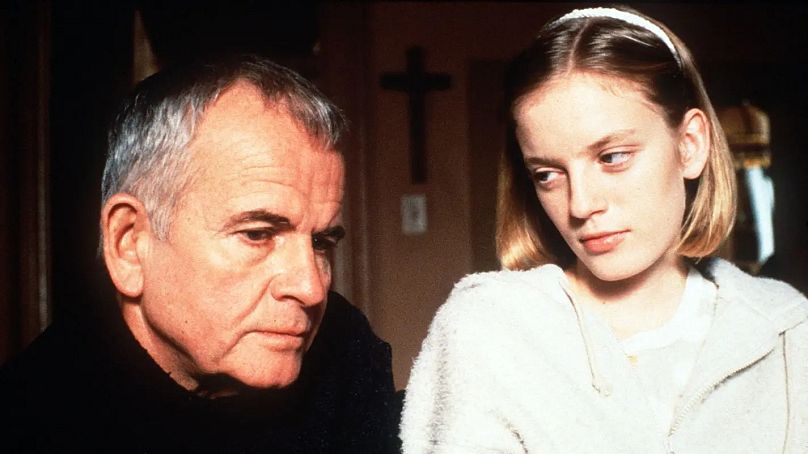

Two of his books were adapted into acclaimed film releases in the late 1990s: The Sweet Hereafter, directed by Atom Egoyan and starring Ian Holm, and director Paul Schrader’s Affliction, which earned James Coburn an Academy Award for best supporting actor.

“Sabotage and subversion”

Politically active, Banks also took a stand against the American military intervention in Iraq and against the Patriot Act. He was also outspoken about the state of his country:

"As a writer, I am fortunate. But as an American citizen, I'm a pessimist," he said in an interview in the French newspaper Le Monde in 2016. "The middle class has become poorer, Americans no longer believe that their children will live better than they do, or even as well."

He also chaired the International Parliament of Writers from 1998 to 2004, founded by Salman Rushdie, and founded Cities of Refuge North America, a network of safe havens for exiled or threatened writers.

Banks liked to say that literature was not the only form of storytelling.

"I was born in the 1940s. Hemingway and Faulkner were still alive and Fitzgerald had just died [...] At that time, the novel was the major form for telling stories," he told Le Monde. "If I were 20 years old today, I'm not sure I would become a novelist. It's very archaic! I think I would be a director for the Internet, because it is the dominant form for telling stories."

His intentions could be resumed in his narrator’s closing lines in ‘Continental Drift’:

“Good cheer and mournfulness over lives other than our own, even wholly invented lives - no, especially wholly invented lives - deprive the world as it is of some of the greed it needs to continue to be itself. Sabotage and subversion, then, are this book’s objectives. Go, my book, and help destroy the world as it is.”

He is survived by his fourth wife, poet Chase Twichell, as well as his daughter from his first marriage Lea Banks, and his three daughters, Caerthan, Maia and Danis Banks, from his second marriage.