Chega, Portugal's third largest party, brought toxic racist and anti-migrant narratives to the country's mainstream politics - yet it strongly denies being far-right, preferring to be considered a populist party.

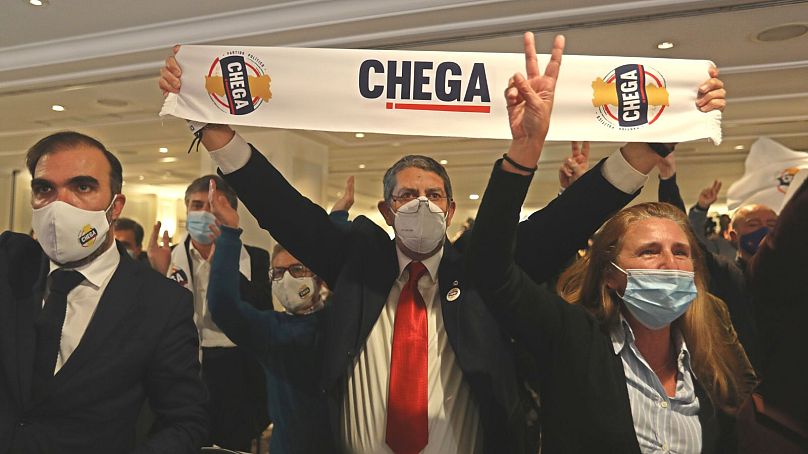

In 2019, the newly-formed rightwing political party Chega! - which can be literally translated to the English ‘Enough!’ - conquered one seat in the Portuguese Parliament. Roughly 3 years later, in the 2022 general election, it multiplied that result winning a total of 12 seats after receiving 7.2% of votes.

It was an astounding rise for such a young and controversial party, which quickly inserted itself in the broader landscape of European populist and right-wing parties, courting the far-right with its narratives against migrants, the LGBTQ+ community, and Muslims but always rejecting being described as such.

“It was really a huge shock,” activist Catarina Viegas told Euronews. “People weren’t happy with the economical situation in the country, then there was COVID - Chega filled the gap between the promise of the government and what they could not deliver, and the media normalised their far-right narrative,” she added.

For many observers outside Portugal, the rise of the party also came as a surprise. “There are a lot of people who didn’t realise that there was such a large, far-right scene in Portugal, because historically, since the end of Salazar [in 1974], this hasn’t really been the case,” Heidi Beirich, co-founder of the Global Project Against Extremism (GPAHE), told Euronews.

“Portugal seemed to be bucking the trend that you see in places like Italy, Sweden, France, and so on,” she added.

But then came Chega, now the third most popular party in the country, with a realistic chance to come into government in the future.

“Chega is a deeply anti-immigrant, anti-Roma, anti-LGBTQ party,” said Beirich. “They demonise immigrants. Their leadership, including their charismatic leader André Ventura, have said horrible things about the Roma, calling them a safety problem - among other things,” she added.

“Ventura has also talked about things like the great replacement conspiracy theory, which is a white supremacist idea that immigrants are going to replace sort of native Portuguese in Portugal.”

For these and other reasons, the GPAHE has recently added Chega to its list of hate and extremist groups in Portugal. There are 12 other groups in the list, including other older parties which pre-dated Chega, Beirich said, but they never reached the electoral success of Chega, like Alternativa Democrática Nacional and Ergue-Te, previously known as Partido Nacional Renovador (PND).

But the decision to list Chega as an extremist party was controversial in Portugal, where the party insists on considering itself populist rather than far-right. Euronews has contacted Chega for comment but did not receive a response.

"They say they’re not racist"

“There has been some disagreement among academics about how to characterise Chega. For the moment, my opinion is that Chega is a populist radical right party, and not an extremist right party,” Cátia Moreira de Carvalho, a researcher interested in extremism, terrorism, psychology and politics at the University of Porto told Euronews.

“This is because Chega clearly has a populist agenda, as it views the ‘pure people’ in opposition to the ‘corrupt elites’,” she added. “Besides, Chega espouses illiberal opinions and its aim is to have this kind of illiberal democracy established in Portugal.”

The extreme right wishes to abolish any form of democracy and resorts to violence to pursue their goals, de Carvalho said. “For the moment, this is not what Chega has been done, nor it seems to me that it will happen in the near future.”

For some, the difference is just in appearances.

“They’re definitely far-right, their narrative is far-right, but they seem themselves as a populist party,” Viegas said. “They say they’re not racist, Portugal is not racist, they make themselves the defenders of those who feel unhappy about the current situation in the country, play them as victims of the system. And that resonates with people who would not consider themselves to be extremists.”

De Carvalho said that since Chega got their first seat in the Parliament in 2019, “hate crimes and hate speech have been on the rise in Portugal.”

“Before that, in 2018, a survey led by Eurobarometer demonstrated that Portugal was the second country in Europe that had the most positive view on the integration of immigrants, with around 80% of people considering it a positive thing,” she added.

A well-connected party

While publicly rejecting the identity of far-right party, Chega’s charismatic leader Ventura has been aligning with the leaders of similarly populist and far-right parties in Europe, like Italy’s Matteo Salvini - head of the League party -, France’s Marine Le Pen, and Spain’s Vox’s leader Santiago Abascal.

The far-right “was not present in mainstream politics in Portugal before Chega,” de Carvalho confirms.

“Portugal was even considered a successful case in this regard, somehow immune to the far right. But nowadays, besides the increasing support of Chega, we are witnessing a normalisation of Chega’s views in the right wing mainstream parties,” she continued.

“For example, the leader of the biggest opposition party said recently that Portugal should look for immigrants that can have a better interaction with the Portuguese people. In other words, he means to have exclusionary measures to welcome immigrants, to open the doors to those who are apparently similar to the Portuguese, and close the doors to others,” she added.

“This is line with the politics advocated by Chega. And to me this is very concerning, because it increases polarisation and approximates moderate right wing parties to radical populist right policies and frontiers between them can become increasingly difficult to draw.”