Many have been in the U.K. so long that they assumed they would never need to present documentation to prove they were in the country legally.

LONDON — Jamaica-born Beverley Boothe followed her parents to Britain in 1979. She says her mother and father both had U.K. citizenship. She hasn't left the country since.

So it was a shock when Boothe, now 56, got a letter informing her that she would be deported from where she's studied, worked and raised five children.

"This is my life. Here. I've got my children, I've got my grandkids," she told NBC News.

Boothe isn't alone. Thousands of similar cases have emerged, unleashing a scandal that has engulfed British Prime Minister Theresa May.

Other Caribbean-born U.K. residents, including many who are elderly, say they have been threatened with deportation, with some detained and denied access to health care and benefits. The revelations have prompted accusations that the government has betrayed a generation of black Britons who helped rebuild the country following the devastation wreaked by World War II.

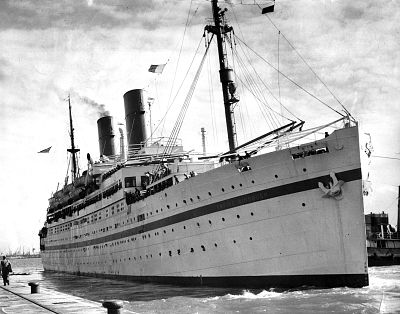

They became known as the "Windrush" generation, after the ship that brought the first 492 passengers from Jamaica, Trinidad and other islands to Britain in 1948. A total of 500,000 workers and their families were eventually invited to the U.K. from former colonies and granted citizenship as subjects of the empire.

Many of them have been in the country so long that they assumed they would never need to present documentation to prove they were in the U.K. legally.

The scandal was exacerbated last week when it emerged that many of the Windrush generation's original landing documents had been deliberately destroyed by the U.K.'s interior ministry, known as the Home Office, in 2009. In many cases, this was a key piece of evidence needed to prove an individual's citizenship status.

"The Home Office destroyed the evidence that gives people to opportunity to say, 'Look, of course I am British,'" opposition lawmaker David Lammy said. "It's very, very hard when you ask these people in their 60s to go back to the 1950s and 1960s and find their documentation."

Critics blame official incompetence and callousness, as well as an immigration crackdown introduced by May when she was in charge of the Home Office from 2010 until 2016. May pledged to create a "hostile environment" in order to deal with illegal immigration, but many now say the policy has created problems for those in the country legally, too**.**

As a result, rather than simply being certified by officials at the border, peoples' status now has to be checked by banks, landlords, employers and others.

"People face fairly intrusive immigration checks in every aspect of their lives," said Satbir Singh, the chief executive of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, a British legal charity. "Many people who have every right to be in the U.K. don't necessarily have all the paperwork."

Critics say that as a result of the demand for paperwork, the Windrush generation and their children have lostjobs and been denied access to life-saving cancer treatment, made homeless and, as in Boothe's case, threatened with deportation.

Boothe says her parents arrived from Jamaica as Commonwealth citizens — members of Britain's overseas empire that largely dissolved after the Second World War who were legally allowed to come to the U.K. as citizens of the "United Kingdom and Colonies." Boothe followed them as a teenager in 1979, on a Jamaican passport.

In 1980, Boothe said she was given indefinite leave to remain, which granted her the right to live, work and study in Britain, as a result of her parents' status.

"We’ve done what we have to do — build up the country — it’s like they want to say, ‘We don’t want you.’"

Her problem started when she lost her passport — stamped with the evidence she needed to prove she was in the country legally — and received a deportation notice by mail in 2013. Then came relentless phone calls telling her she had to leave.

"This was just out of the blue," she said. "It was horrible."

Since then, she has provided birth and death certificates for her British family and her degree certificate in her attempt to prove her status.

Boothe eventually received a short-term residency permit in 2015, and was able to get a job caring for elderly and sick people, but that has since expired.

It's also affected her family. Despite her children being British citizens, they have struggled to get passports. She also says she hasn't been able to able to gain access to taxpayer-funded health care.

The scandal has generated fury across the U.K. Lammy, the lawmaker, whose parents came from the former British colony of Guyana, organized a letter to the prime minister from more than 140 fellow members of Parliament expressing their concern.

His impassioned speech to Parliament last Tuesday, in which he slammed May's successor as home secretary, Amber Rudd, was widely shared on social media. In it, he described a "day of national shame."

Lammy told NBC News he sees parallels with President Donald Trump's move to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program.

"It's exactly the same rhetoric that we've seen from Theresa May pandering to a new far-right temperament than has grown up in Britain," he said. "The system has become infected."

For the government's part, Rudd issued an apology for the scandal last week.

May later apologized to Caribbean leaders and established a task force, which as of Saturday had investigated more than 280 cases. She also said the government would compensate those affected.

On Monday, Rudd told Parliament that 4,200 cases out of a total of 8,000 had been reviewed so far. She said no one had been found to have been wrongly deported, although she described some of the cases as "harrowing."

Rudd said the fees of obtaining citizenship would be waived for anyone affected. Lammy responded by saying the Windrush generation were "citizens when we invited them 70 years ago."

And the issue is unlikely to go away for the government.

Of the more than 500,000 former colonial subjects who arrived before a 1971 law change, 57,000 are thought to be especially vulnerable because they never officially took steps to formalize their immigration status, according to Oxford University's Migration Observatory.

And with negotiations over Britain's exit from the European Union ongoing, many of the 27 remaining E.U. states will be concerned that their citizens who are legally in the U.K. don't find themselves in a similar predicament.

"Of course they're looking at the Windrush generation, who were given the same promises 70 years ago, who are now being treated in such a cruel and inhumane way," Lammy said. "I do think it will affect the way our European partners negotiate with us on this issue."

Even if a solution to her case is found, Boothe said something has changed about her relationship with the country that has been home for decades.

"I feel more than betrayed," she told NBC News' British partner ITV News. "Our parents were invited here. ... We've done what we have to do — build up the country — it's like they want to say, 'We don't want you.'"