France has been ranked number one among developed countries when it comes to inequalities in its school system. Valerie Zabriskie reports on what went wrong in the country of "Liberté, Egalité et Fr

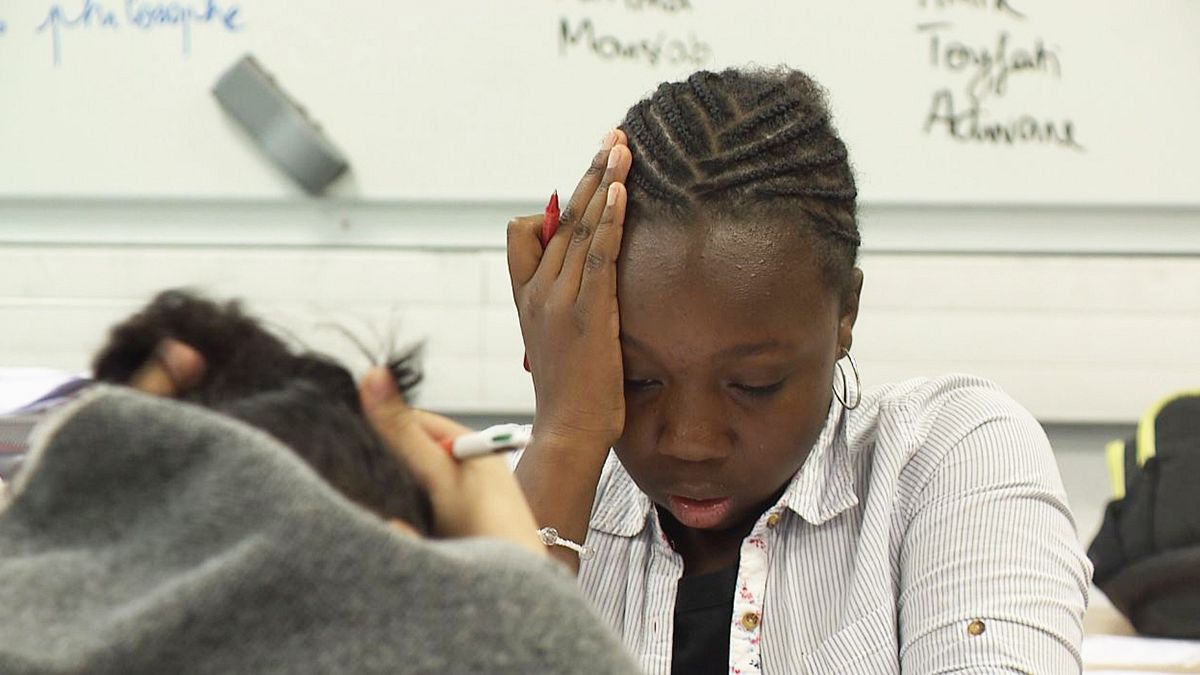

At the Jean Moulin middle school in the French city of Marseille, hands are raised, questions are asked, and answers are given. There is also discipline and respect.

The school is in one of Marseille’s poorest neighbourhoods. Most of the students have financial aid and their parents earn under 1,000 euros per month.

It’s also what is known as a priority education school.

“The most important thing is that there are less students than in a regular middle school where you can have up to 27, 28, 29 or 30. Here there is a limit of 24 by class. It’s more comfortable this way.

‘And also we’ve put in place groups based on needs. This means they’re by groups of competence. With two classes, we created three groups of competence, “ Arnaud Sallaberry a teacher at the school explained.

The priority education system was introduced in 1982 to help schools in poorer areas of France. It has already been reformed twice in three years.

Dominique Duperray has been the school’s principal for five years. For him the changes since he arrived are striking.

“Before the reforms, 40 percent of the students passed their middle school exam and barely 50 percent went on to high school. Today, we have 70 percent and sometimes even more who pass their exam, and 100 percent who go on to high school, some in a general high school, others in a vocational one.

‘So the fact that we get extra funding as a priority education school, plus the involvement of the school staff in constantly innovating the school curriculum, allows us to improve our students’ school career,” stressed Dominique Duperray Principal of the school.

But is this school more the exception than the rule when it comes to France’s state educational system?

Especially when a recent report which evaluates school systems among OECD countries revealed that France is in first place when it comes to inequalities in its school system.

There are more than 9000 primary and middle schools in France which are classified priority education. One out of five children attend these schools.

Euronews went to Bobigny, on the outskirts of Paris. Our request to film priority schools here were turned down. The official reason: they’ve been inundated with requests since the report.

“How did France become number one when it comes to inequalities in its school system among OECD members? Here we are in one of Paris’ most disadvantaged neighbourhoods and again we were not allowed to film inside the school. So we asked its director to come outside and talk to us,” reported euronews’ correspondent Valerie Zabrinski.

Véronique Decker has worked in Bobigny for 30 years. And although her primary school is classified priority education, she says she’s seen little extra financing.

All her students come from immigration backgrounds. Their families live in social housing. She is not surprised about France’s ranking.

“There is no equality between public and private schools. The private schools are being favoured by the funds they get from parents, by being able to choose their students. We can’t get any funds from parents, and that’s good. And we can’t choose our students, which is also good.

‘But as a result there isn’t any equality between private and public. There isn’t any equality between different public schools as well since the French state accepts that on its territory, there are areas of segregation and this means that as a result, the schools in these areas are segregated schools,” explained Veronique Decker Head of Marie Curie Primary School.

Laurence Blin wants justice. Not for her but for her sons. Her oldest, who is 14 years of age goes to a priority education school in Bobigny. But for her, her son’s school is anything but priority.

Teaching hours have been reduced by 25%, money promised to hire and train more teachers never happened despite the arrival of 50 new students last year alone.

Laurence and other parents have filed a complaint. They’ve argued that their children are victims of inequality – something which goes against the country’s educational codes written in the constitution.

“Teachers not being replaced is a big problem. When my son was in sixth grade, for a whole trimester, he didn’t have an English teacher. In 7th grade, every time, during the first trimester, no history-geography teacher and during two trimester, no art teacher.

‘And then in eighth grade, during the first month, no science teacher. It’s incredible. How can you expect these children to succeed when there is such an absence? How can they have the same level as children whose teachers are present all year round?,” she pointed out.

How did France’s school system get to this point? What went wrong?

Nathalie Mons headed the report which revealed France’s inequalities in its schools.

Inequalities she says that have many different facets. But she’s hopeful.

“In France, for the past 30 years, we’ve been carrying out educational policies that are very similar. And the results haven’t proven to be very productive in the fight against social inequalities at school. For example, since the beginning of the 80’s, we’ve led policies of priority education in which no research has proven any positive results.

‘It’s obviously very important to give more educational resources to schools facing difficulties. It’s necessary. But when we looked at the resources available, we realized that these extra resources in question had very little to do with students learning,” revealed Nathalie Mons President, CNESCO school system evaluation.

Back in Marseille, it’s diploma time. Students who graduated last year have come back for their certificates.

It’s a moment of pride but also of emotion. Although this school’s record has improved, the hope is that more will be done so that it will no longer be the exception but the rule.

“In France, French schools are no longer a way to climb the social ladder. So we have to change this. We have to, and both families and students are asking for this, we have to bring back trust to schools,” concluded Dominique Duperray.