Our governments must be willing to put their money where their mouth is, ensuring that state uses of AI are subject to the same reasonable rules and requirements as any other AI system, Ella Jakubowska writes.

Promises to solve society’s biggest problems, as well as claims of the risk of human extinction, seem to be the hottest artificial intelligence topics dominating headlines.

But this focus on a promised far-away future often takes attention away from real and present risks.

One of the issues we’ve dangerously overlooked is that the use of AI systems will widen the already vast power imbalance between states and people.

As subjects of police and other authorities’ use of AI technologies, this should worry each and every one of us. The rapidly increasing use of AI systems in police and border, welfare, and education contexts is transforming public administration and public spaces beyond all recognition.

It is high time that we apply well-established procedural rules and safeguards to the context of AI. Claims that “over-regulation” will “kill” innovation are a red herring, distracting from the fact that already disproportionate government — and corporate — control over our lives will be entrenched if we fail to apply the same checks and balances to AI systems that we do to all other areas of life.

Yet EU governments are pushing back sharply, attempting to empty all meaning from legislative attempts to safeguard people against the most harmful uses of AI.

EU Artificial Intelligence Act nears its close

In the EU, the much-anticipated AI Act is reaching its final stage of negotiations. One of the key principles of this bill has always been that people and societies need to be able to “trust” in the use of AI systems, in particular knowing that risky systems are properly regulated and that extremely risky systems are prohibited.

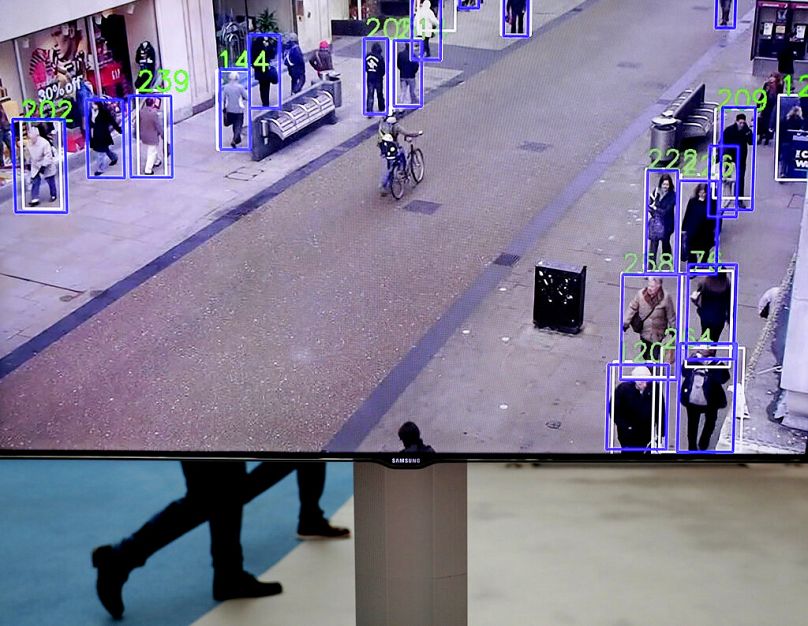

Civil rights activists have argued that invasive and manipulative practices such as public facial recognition and predictive policing need to be outright banned. Biometric mass surveillance of protests, shopping streets, parks and other public spaces cannot be accepted in a free society.

Yet attempts from the European Parliament to stop governments from being able to use AI systems in this way are being stonewalled by at least twenty-six of the EU’s member state governments.

These member states are prioritising convenience, and even austerity goals, over proper checks and balances that would protect us from being harmed by risky AI systems.

The underpinning argument from EU governments has been that we must trust them to use these systems in ways that will keep us safe. They have argued that prohibitions are too blunt an instrument, and that safeguards are enough to ward off abuse.

Trust in police AI must be earned

Yet when it comes to other state uses of AI, the narrative could not be more different.

The same governments asking us to trust them to use public facial recognition and predictive policing in a "safe" way are the very same ones arguing that they shouldn’t have to follow AI rules when it comes to the most dangerous state uses of AI — like the use of AI by the police and migration authorities.

These are the very cases where we most need transparency and accountability. Digital technologies do not change the fact that to police by consent, states rely on the will and the trust of the people they govern.

But how are we supposed to trust our governments to safely use AI systems when they refuse to follow any rules that would protect us from the harm that this potentially dangerous technology can cause?

EU states will not gain people’s trust by keeping their use of AI technologies in the shadows, by rejecting controls that guarantee safe system design, nor by allowing unscrupulous deals with AI corporations hungry for profit.

The opacity and technocracy of the AI industry make it even more important than ever that the public is given a reasonable insight into how our governments are using these systems.

Without this transparency, we risk having AI systems that exacerbate discriminatory and harmful patterns, trapping people in loops of false accusations and trials by algorithm.

Prohibiting the most dangerous uses

Despite claims by hawkish government officials and purveyors of AI systems, prohibitions on unacceptably harmful uses of AI systems are not a blunt instrument.

In human rights terms, we talk of a spectrum of safeguards: from more minimal safeguards for less risky systems, all the way through to a full ban for when we know that something just isn’t compatible with a just society.

The reality is, only a very small number of well-defined AI use cases are on the table for an EU-wide ban in the AI Act. Even then, the member states seem keen to make exceptions.

Take public facial recognition — according to the original draft, only the use of systems in “real-time”, “at a distance”, by police, and in “publicly accessible spaces” would be the subject of the ban.

Delay the matching by an hour, do it in a kiosk or by an administrative authority, or any other number of exceptions, and it would no longer be prohibited.

Civil society groups have argued, however, that the protection of rights to privacy, dignity, free expression and equality necessitates a full ban on mass surveillance and arbitrary uses of biometric systems, and strict controls on other uses. EU governments, however, are pushing for safeguards so weak, they are meaningless.

The problem of double-thinking

The double thinking of EU governments on these issues betrays the lack of substance to their arguments.

The recent US Executive order on AI, for example, showed that it is indeed possible to include law enforcement and national security agencies in the scope of AI rules.

Our governments must be willing to put their money where their mouth is, ensuring that state uses of AI are subject to the same reasonable rules and requirements as any other AI system.

And in the small number of cases where the use of AI has been shown to be just too harmful to make safe, we need prohibitions.

Without this, we will not be able to trust that the EU’s AI Act truly prioritises people and rights.

Ella Jakubowska is a Senior Policy Advisor at European Digital Rights (EDRi), a network collective of non-profit organisations, experts, advocates and academics working to defend and advance digital rights across the continent.

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.