The death of the eighth and final president of the Soviet Union has sparked debates that are particularly relevant now when Russia is involved in the invasion of its western neighbour.

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev, the eighth and final president of the Soviet Union, has sparked as much debate and divisions as his actions did during his lifetime.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

For most of Europe and the West, the 91-year-old Gorbachev will be remembered for his time at the helm of the waning socialist superpower and for steering it towards a liberal reform agenda.

For nationalist Russians, he will always be reviled as the culprit for the demise and breakup of their glorious Soviet communist empire.

Elected Soviet leader in March 1985 at 54, the child of Russian and Ukrainian peasants rose from humble beginnings during the Stalinist period to the very top of the Communist Party.

His policies of perestroika, meaning restructuring, and glasnost, meaning openness, led to a thaw between the two main Cold War blocs that had been on the brink of war since the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Debates around his legacy are particularly relevant at the current moment when Russia is involved in the invasion of its neighbour — a neighbour whose independence Gorbachev did not interfere with in 1991.

How did Gorbachev influence today's Europe?

Mikhail Gorbachev eschewed the Soviet Union’s rigidly centralised legacy, aiming to reverse the stagnation experienced during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev, and eventually grew wary of communism altogether.

But it was not until the late 1980s that his desire for peace shone through amid major domestic upheaval, especially in the USSR’s member states.

Choosing to let the Iron Curtain fall freely — which paved the way for the independence and democratisation of a number of Europe’s formerly socialist and communist societies — went against the expectations of the West that the Soviets would cling to the rungs of power even through violence, said Professor Vladislav Zubok, who lectures on international history at the London School of Economics.

“Gorbachev wanted to open up the country and he viewed the Soviet Union as part of Europe, part of the trans-Atlantic community, not something opposed to it,” Zubok said. “And he contributed most to a new European reality by not doing anything, just talking.”

“One thing that he talked about that was fitting for the mood at the time, the mood of sudden excitement, exhilaration, liberation — something that was very intangible but very profound at that moment — was when he began speaking about a common European home.”

Gorbachev’s notion of the Russia-dominated Soviet Union belonging together with the rest of Europe came with no expectations that Moscow would be the one dominating the relations by force or dictating the terms, either.

“That was exciting and pretty much unbelievable because it came from the general secretary of the Communist Party,” Professor Zubok, who has authored several books about the Soviet Union and its final days, explained.

“His design was to try to carefully domesticate the Soviet Russian imperialistic impulses and to bring Russia, step-by-step — at that time, not a state but the core of the Soviet empire — closer and pull it into Europe.”

“This was meant to change that part of dependency that Russia had in the past, of being either one of Europe’s empires or opposing Europe as one of the empires," Zubok told Euronews.

Although his pan-European sentiments were vaguely formulated and mostly meant for foreign consumption, according to Zubok, his desire was genuine, and the designs were grand.

Yet the combination of a shattered economy that was in shambles even when he came to power, the rise in crime and unemployment, and the mass impoverishment all spelt trouble at home.

Outside of Russia, Soviet member states and satellites alike were quickly transitioning to some form of independence and liberal democracy.

First, it was Poland, where the Solidarność movement scored an unprecedented victory in the country’s first democratic elections in June 1989.

This resulted in fears that Gorbachev could use force to restore its communist government — but that did not happen. Then the Berlin Wall famously fell in October 1989. Gorbachev and the Kremlin again did nothing.

“That disappearance of fear was something almost intangible, right? You could believe it or not,” said Professor Zubok.

With pressure on Gorbachev rising, things did take an ugly turn, with the independence of the Baltic states — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — being the straw that broke the camel’s back.

In January 1991, a violent crackdown was launched in Lithuania, where the Soviet military killed 14 and injured another 140 in an attempt to prevent it from leaving the USSR over the course of three days, and left a lasting stain on his image as a pacifist.

But according to Zubok, Gorbachev was an outlier regardless. Even Brezhnev, who did not shy away from using force in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Afghanistan in the 1980s, considered himself to be a peacemaker.

Yet Gorbachev openly rejected the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine, whereby the Soviet Union had the right to intervene in other socialist or communist countries if there was a direct threat against those in power.

“Gorbachev was in charge of the most violent political force in the world, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,” Zubok said. “He used force, but later he always said he didn’t want to do it, ‘it was imposed on me by dark forces’, reactionaries, stuff like that. So it’s a major paradox of history.”

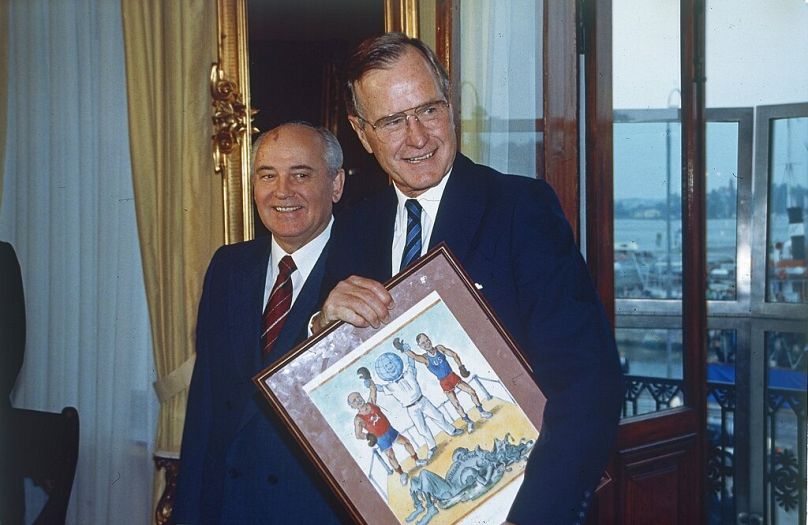

“Again, it was a matter of belief. Some leaders mistrusted him, Thatcher trusted him, Bush Sr. at first said he was all talk, then in June ’89 he said ‘oh, Perestroika is Gorbachev.’”

“So, as the world began to realise that he would not use force to stop changes, then the change turned into an avalanche,” Zubok concluded.

What did Gorbachev think of Ukraine?

Gorbachev was born in Privolnoye, Stavropol Krai or in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. At the time, Privolnoye had an evenly split ethnic Ukrainian and Russian population, something Gorbachev evidently grew to believe was normal.

“Gorbachev was himself of mixed ethnic origins, Ukrainian-Russian, and until the last moment he couldn’t believe that Ukraine would be separate from Russia,” Zubok explains.

He saw Leonid Kravchuk, the main leader of Soviet Ukraine who also died in May of this year, and Boris Yeltsin, Kravchuk’s Russian counterpart, as “dangerous opportunists” who fanned the flames of ethnic nationalism among their respective populations.

“They were pitting the two people against each other. ‘How came can my relatives living in Ukraine be in a foreign country?’, he kept exclaiming,” said Zubok.

The logic of nationalism, which is at the heart of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine today, was not something Gorbachev accepted as an inevitability.

“Many, many Russians sort of kept thinking like him, so when all of a sudden Ukraine began to say, ‘I’m not Russia, I will not do this, I will not do that,’ there was a lack of understanding,” concludes Zubok.

How do Russians perceive his legacy?

While the West saw Gorbachev as a visionary who was willing and capable of ending the Cold War — rewarding him for his efforts with a Nobel Peace Prize in 1990 — for most Russians, he was an incompetent figure at best.

At worst, he is seen as a traitor that destroyed a country they were so proud of, Sergey Radchenko, the Wilson E. Schmidt Distinguished Professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies told Euronews.

This dissonance is the result of divergent historical perspectives, Radchenko argued.

“For the West, the end of the Cold War was a moment of joy. It signified the triumph of Western values, the triumph of freedom, of democracy, the dismantling of the Iron Curtain,” he said.

“That also could have been the message for the vast majority of Russians. However, things did not go well for them because with those freedoms also came great economic hardships that were occasioned by the Soviet collapse.”

“And many Russians blamed those things on Gorbachev although, in all truth, he wasn’t responsible for them because the system he inherited had deep flaws and some would argue was in many ways unreformable,” Radchenko explained.

During the final months of the USSR, Gorbachev was a victim of a failed coup, eventually ousted by the first Russian President Yeltsin, who shut down the Communist Party, arranged the dissolution of the Union, and told Gorbachev to resign and vacate the Kremlin by the end of 1991.

The rise of President Vladimir Putin at the turn of the millennium, whose toxic nationalist beliefs and tendency for historical revisionism exclusively highlighting Russia in a positive light, led to only the most enlightened Russians understanding and appreciating Gorbachev’s contributions.

Yet most fail to understand that Gorbachev did not want to see the Soviet Union fall apart at all, Radchenko explains.

“He did not want the dismantling of the Soviet Union. He wanted to reform the Soviet Union. And once he realized his economic reforms were not delivering, he then pursued political ones in order to break the logjam and do it the quick way,” he explained.

“This was different from the Chinese who, as Deng Xiaoping put it, pushed for reforms by ‘crossing the river by feeling for the stones.’”

“Well, Gorbachev would have none of that. He would jump into the river and see how fast he could swim.”

Can Gorbachev’s dream of Russia as a full-fledged democracy ever come true?

In the end, the problem with the reforms was that they were decided upon by those at the top of the political pyramid, with very little buy-in from the bottom.

“That’s the fundamental problem of this whole reform experience. It lost legitimacy in the eyes of the public, and the public began to seek and long for a strong leader who would rule with a strong hand, so that’s where I think we ended up now,” Radchenko explained.

Once Putin properly got hold of power in the country, he returned to the politics of dominating through violence, involving Russia in a series of wars and conflicts, including Chechnya, Georgia and Ukraine.

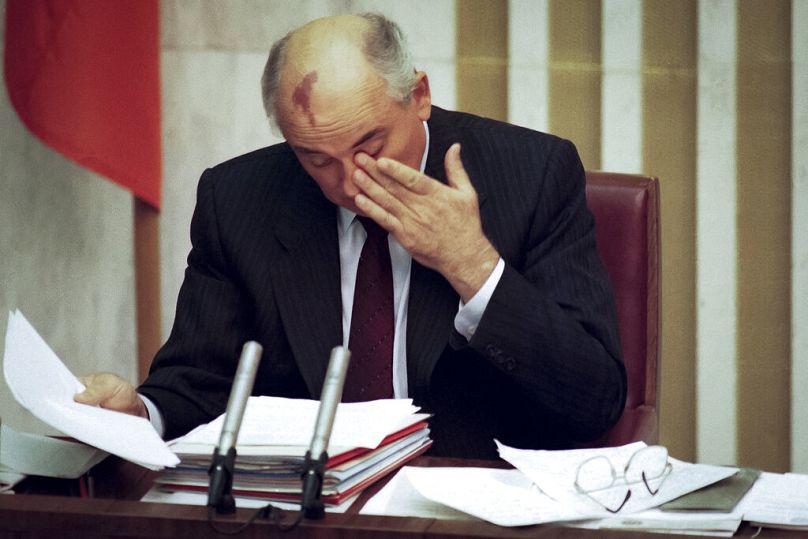

Meanwhile, Gorbachev was largely forgotten, with the news of his death in a government-run hospital in Moscow formulated in a curt and matter-of-fact manner, “after a long and difficult illness.”

“I think Gorbachev died a disillusioned man. He lived long enough to see many of his key accomplishments completely dismantled by Putin, and that’s not a happy position to be in,” Radchenko, a notable Cold War historian, said.

“Who could he blame? The Russian people, I suppose, in that they proved so short-sighted and so blind as not to understand, to appreciate the chance that they were given.”

“A chance that they had not had and may not have for many more decades, and they squandered it. So I suppose Gorbachev blamed the Russian people for failing to understand what freedom is and failing to love freedom,” Radchenko explained.

And with the latest act of aggression against its western neighbour Putin — and Russia along with him — became pariahs once again, with most of Europe and the West isolating the nation politically and economically and equating it with moral evil.

Yet Radchenko believes that a day will come when ordinary Russians will remember Gorbachev’s legacy as they attempt to rebuild their society into a full-fledged democracy that will be a part of Europe after all.

“I don’t think that there’s something specifically genetically wrong with the Russians that they can never understand the virtue of democracy, the virtue of freedom,” he said.

“Other nations have passed through traumatic experiences and have also been called unreformable — of course, I have in mind the Germans first and foremost — and yet, they were able to overcome and put that experience behind them and understand their history a little bit better.”

“I hope Russia will move in that direction. Primarily it’s a function of a changing generation [...] so as time shifts, Russia will also change and have a different view of its own history and perhaps reinvent itself — but it will be a difficult process, judging by how difficult it has been so far,” Radchenko concluded.