The Sarajevo Haggadah survived the Inquisition, two world wars and a military siege. Now a 'homecoming' exhibition for the scroll has sparked a dispute over who has the right to display it.

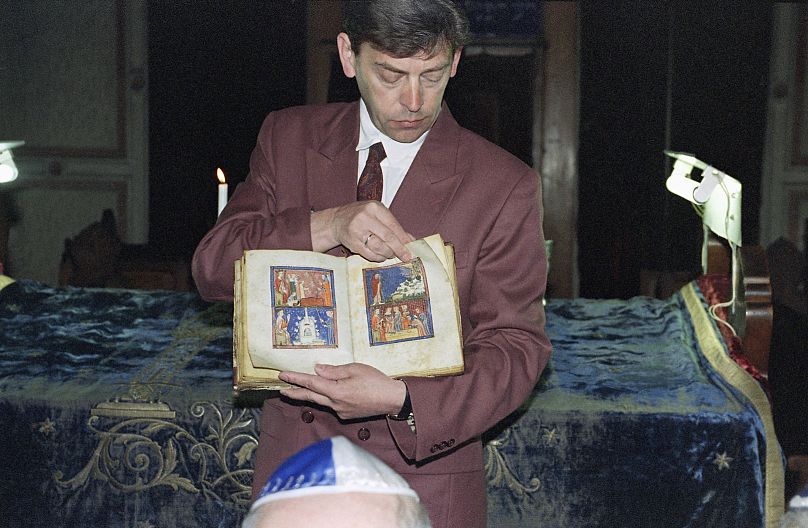

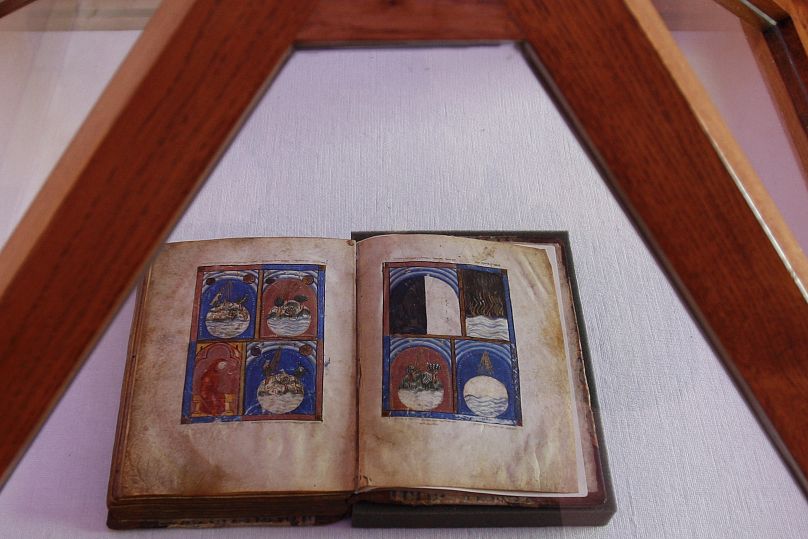

The gold-encrusted and vividly coloured pages of the Sarajevo Haggadah, a medieval Sephardic Jewish manuscript traditionally used during Passover Seder to retell the stories of the Jewish people, is perhaps Bosnia and Herzegovina’s most treasured historical artefact.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The story of its survival is perhaps even more awe-inspiring than the book itself. It escaped the consequences of the Alhambra Decree in Spain, was spared by the Inquisition in Rome and then found a permanent home among the exiled Jewish community in Sarajevo, then a part of the Ottoman Empire.

It survived two world wars, and finally, Bosnia’s bloody conflict in the 1990s.

Now it has been finally brought back to Spain for an exhibition after six centuries of exile.

Or has it?

The dynamics of artefacts being traded from one museum to the other for special exhibits are often much more complex than the exhibition seekers might be aware of.

The exhibition in late September in Spain’s capital only showed 50-something facsimile prints out of a 142-page tome.

Despite that, countless headlines lauded the fact that such a precious artefact was being displayed.

Unlike the rest of the Haggadot found in the world, the Sarajevo Haggadah has colourful illustrations, poems written by Hebrew authors from the culture’s Golden Age, as well as depictions of human faces which is in contravention with Jewish customs.

Labelled as a “homecoming,” the pages on display at the Centro Sefarad-Israel in Madrid nevertheless drew attention to both the book’s unique artistic value as well as its history.

The Sarajevo Haggadah is one of fourteen remaining Haggadot that survived the expulsion of Spain’s Jewish community in 1492.

Originally from Barcelona, it was most likely made as a wedding gift. The leather pages are hand-illustrated, and its lavishness is best gleaned from the fact that it features seven distinct nuances of gold-infused colouring, says the president of the Jewish Community of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Jakob Finci.

The precise manner in which it was preserved and brought to Sarajevo is unknown. But a few stops along the way can be gleaned from the manuscript itself, such as the seal of the Catholic Church inquisitor who inspected it in the early 17th century.

“It was saved in Rome during the Inquisition because there is a stamp and note on it from 1609 after it was checked by Inquisitor Iusterini stating that it has no heretical content,” Finci explains.

As such, it would be spared from destruction by Catholic Church authorities who would claim it questioned the authority and teachings of the Church.

This is ironic, considering that the depiction of the Earth on the same page is that of a globe-shaped sphere — something that Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for only nine years prior.

Then, it made its way to Sarajevo.

“The presumption is that two Venetian rabbis who would often come to Bosnia eventually brought it to Sarajevo,” he illustrated.

The Sarajevo Haggadah was named after the Bosnian capital it has called home since at least 1894, when the Kohen family of Sarajevo sold it to the National Museum. The Sephardic family were descendants of the community who found refuge in today’s Bosnia since the Ottoman Empire was one of the few parts of Europe to accept them after their expulsion.

There, it survived two world wars, in a no less dramatic way. During the Second World War, it was hidden under the floorboards of a mosque. The museum’s director at the time told the Nazis who came to take it that he had already given it to a German officer who paid him a visit right before they did.

In the most recent Bosnian war that ravaged the country between 1992 and 1995, the Haggadah was extracted from the museum and kept in the country’s National Bank. The museum found itself wrecked at the frontline of the Siege of Sarajevo, with soldiers from the two sides meeting a stone’s throw away from its main entrance.

The Haggadah has long surpassed its original religious purpose. Today, it is beloved by all religious communities and is a point of pride for Bosnians of all religious or ethnic denominations, says Finci.

“The symbolic value of the Sarajevo Haggadah is that something that is holy to one group of people was protected by another religious group, too. Every time the Haggadah was saved, it was not the Jewish community that saved it,” he concludes.

Modern-day drama

Its exhibit in Spain’s capital did not come without its own turmoil.

Mirsad Sijarić, the director of the National Museum — which has had the Sarajevo Haggadah in its possession for almost 130 years — said that the exhibition was not approved by the museum, while the copyright held by the Rabic publishing house, the co-organiser, had expired.

“It’s the age-old practice where anyone who sees an interest uses the museum’s resources without elementary respect,” Sijarić told Euronews.

“From my point of view, it’s as if I decided to do an exhibition of a copy of the Mona Lisa or a Caravaggio or a Cézanne without asking the relevant museums who are keeping them for their permission.”

A contract from 2004 is at the core of the spat. While the museum claims that the contract was only valid for five years, the publishing house insists that it had no expiration date.

Now, the museum has its own replica and a Haggadah-themed exhibition travelling around Europe. Currently, it is on display in France, with stops in Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia planned along the way. Sijarić feels that the museum was circumvented and had its rights ignored on a whim.

“Some seem to willfully ignore the fact that the museum made sure that the Haggadah is on display in a special room for everyone to see, that we have made our own facsimile edition in English, Bosnian and soon in French. We’re preparing a Spanish edition too,” he said.

Contrary to some claims, the original can be seen in person at the museum every day at specific times, Sijarić explained.

“I feel like I often get stuck in these arguments while all I want to do is do my job,” he continued. “The museum has 3 million artefacts and the Haggadah is just one of them, and although we give it as much time as possible, we have other work to do as well.”

The 50-something printout pages shown in Madrid aren’t mentioned in the contract made available to Euronews, and the publisher has the right to solely produce two versions of the tome: a “popular,” cheaper version, and an exclusive, limited-edition, luxurious print.

One of the articles, however, actually requires Rabic to promote the Haggadah “at prestigious venues, with the presence of select invitees, representatives of organisations and companies, as well as radio, print and TV journalists.” Goran Mikulić, Rabic’s owner, said he was doing exactly that.

“I did the work for them, promoting both the museum and the Haggadah,” he said in an email, “and we did 11 exhibitions before this one without that ever being a problem.”

Mikulić says his prints were on display in places like Prague’s Grand Synagogue and the Jewish Community in Oslo, and that all of them were for the sake of promotion and not profit.

“I’ve funded all of the exhibitions out of pocket. But more often than not, you have to take risks in order to get a result.”

The Bosnian ambassador in Spain Danka Savić is delighted with the exhibition in Madrid and said that “the reactions were phenomenal.” She also stated that there was no ill will. To Savić, her job entails cultural diplomacy and that is all she was concerned with.

“What matters to me the most is the promotion of the country in the best possible light, especially its culture because that’s one area where we have something significant to offer.”

Abroad, events featuring Bosnia often get reduced to its bloody conflict -- often described as the worst and most vicious on European soil since World War II. The Haggadah, in contrast, brings forth stories of the complexity and richness of a country that has been home to diverse cultural, intellectual, and religious groups.

“Promoting the Sarajevo Haggadah and all of its editions is one of my priorities here, and I don’t see anything wrong about that. I think that the Haggadah’s history is unique and truly special and this is the ideal country to promote it in,” Savić told Euronews.

Savić confirmed that she was aware of the museum’s own facsimile edition and that an exhibition featuring it was in the works.

“I have already arranged another exhibition of the Haggadah paired with a lecture at the Sephardic Museum of Toledo, and we’ll be showing the National Museum’s edition. We got the two directors talking and we are considering doing it in September,” she said.

But Sijarić claims that, despite earlier conversations with the embassy, he only learned about the Madrid event from the press.

“I wasn’t contacted by the embassy, but by a journalist asking for a comment on the ‘good news that the Sarajevo Haggadah is returning home.’ It occurred to no one to contact the museum and ask whether we’d partake. And that’s not okay,” he said.

The disagreement over the exhibition in Madrid, however, revealed a much bigger issue back home. The home country of the Haggadah has one of the most complex and ethnicised political systems in Europe, set in place through a peace agreement from 1995 that grants protections for each of the country’s main ethnic groups -- Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats -- at every level of government.

As such, most of the funds in the country are squirrelled away for various political issues. Funding restrictions and massive debt even led to the museum being shuttered for three years.

'No one cares about culture in Bosnia'

As one of seven so-called “cultural institutions of national importance,” the main problem the National Museum has encountered since Bosnia’s independence is the yet unanswered question of who is responsible for its core funding.

Bosnia does not have a state-level ministry of culture. The ministry of civil affairs, which covers culture but also education, health, and a wide variety of other sectors — as far-ranging as the removal of undetonated mines from the war or citizenship and travel documents — simply doesn’t have the resources to focus on the National Museum.

This led to the National Museum’s closure in 2012. Some 40 employees, however, kept coming to work regardless, maintaining the museum and its collections without remuneration. After a large-scale civic action, the museum reopened in 2015 when other levels of government promised to each provide a portion of the funds needed — around 750 thousand euros annually.

Bosnia is administratively divided into two entities or subnational units, the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska and the Bosniak-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, or FBiH. Each entity has its own assembly and government, overseen by a state-level parliament and council of ministers. The FBiH is further divided into ten cantons, each with its own ministry of culture.

The COVID-19 pandemic made the already meagre funds for culture even more scarce, at a time when all of the institutions were closed to visitors. The FBiH entity cut its culture budget by 40 per cent in 2020, while the Sarajevo Canton took over funding of the National Museum for the remainder of the year. The situation didn’t improve at all in 2021 and it remains dire to this day, says Sijarić.

“We somehow managed to pay out wages for our employees so far, but it looks like we won’t be able to from now on.”

“The state gave us nothing this year. Over the past three years, we got a total of 300 thousand convertible marks [Bosnian currency initially pegged to the Deutsche Mark and now to 0.5 of the Euro] from state-level institutions. We received about 500 thousand marks from different levels of government, which amounts to about one-third of our running costs,” he explains.

Meanwhile, in Spain, the mere presence of a Sarajevo Haggadah-themed exhibition might help the country’s society get a better understanding of the Jewish community that once called it home, says Marcel Odina, director of the Mozaika Jewish Cultural Platform in Barcelona.

“Since the Expulsion — and in Catalonia, the vast majority of the Jewish population was extinguished before 1492 — there was a break in the way the presence of Jews in Spain is perceived,” he said.

“Nowadays, most people in Spain think of Jews as a community that only existed during the Middle Ages and they don’t associate Jewish heritage as relevant or being a big part of the Spanish one, even though it is.“

But even after six centuries, the Sarajevo Haggadah carries enormous emotional weight, Odina explains.

“I really wish I could at one point have the chance to see it physically myself, for me it would be an absolute dream. I think the physical object has a lot of value and importance to a lot of people.”

“At the same time, I feel that there is really a need to try and reach as wide of an audience as possible and to make Jewish heritage and culture more present,” he said.

Odina sees the Sarajevo Haggadah as an artefact that goes well beyond its history -- but also its current place of residence. And in a sense, its wondrous path makes it a valuable gem of world culture.

“These artefacts have gone through a long and complex history and obviously Spain and Catalonia are a big part of the history of the Sarajevo Haggadah. I would also say that Bosnia and Sarajevo, as well as the places it passed, are also hugely important parts of its history,” he said.

“After hundreds and hundreds of years, the heritage of these objects is usually very complex and I personally wouldn’t think of it in terms of property. I get the concern that if it came to Spain some would say, ‘Oh now it belongs to Spain.’”

“But I think it really belongs to everywhere it’s been, everyone who had it at some point and anyone who used it at Pesah Seder -- as well as the people who study and disseminate it,” concludes Odina.

Every weekday, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get a daily alert for this and other breaking news notifications. It's available on Apple and Android devices.