Hydropower projects in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and all over the Balkans are threatening an ecological gem.

There is only one free-flowing river left in Europe, the Vjosa.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

It begins in Greece as the Aoös, before crossing to Albania, snaking through the Balkan mountains, and finally reaching the Adriatic Sea. The Vjosa is central to the ‘Blue Heart of Europe,’ a nearly 6,500 square-kilometre basin of tributaries and wild waterways.

The Blue Heart of Europe spans across the Balkan region, where Europe’s last wild rivers form an extraordinary network of biodiversity and pristine waters. In fact, 80 per cent of rivers in the region are very healthy (a far cry from the waters in Western Europe), with 30 per cent ranked as pristine and 50 per cent as very healthy by a hydromorphology assessment carried out in 2012.

But only Albania’s Vjosa is fully undammed, including all of its tributaries. That’s over 270 kilometres of untamed, free-flowing water - which serves as home to 69 endemic fish species, like the Danube salmon. The banks and surrounding land are also biodiversity hotspots, with many other endangered and vulnerable species living in the forests, including the Balkan lynx.

This extraordinary region is so untouched that we actually know less about the Vjosa river than we do about the Amazon, according to EcoAlbania.

So why does the Blue Heart of Europe need saving?

Hydroelectric power isn’t so clean

The Blue Heart of Europe has experienced a ‘Hydropower Gold Rush’, as campaign groups have dubbed it.

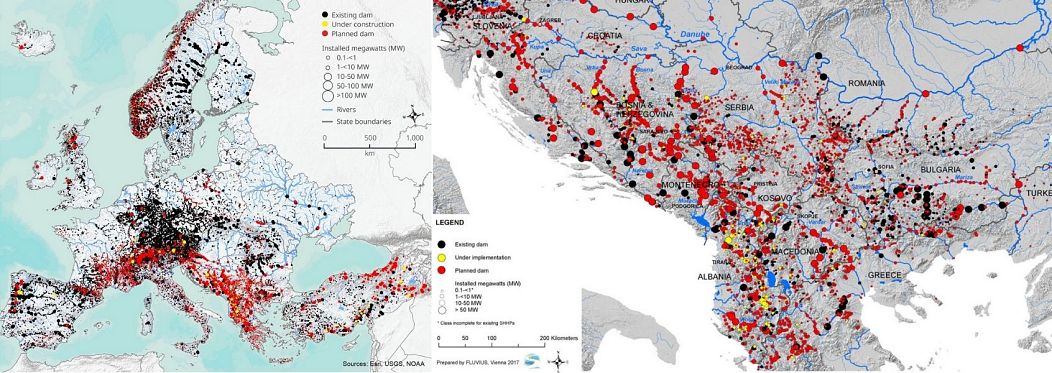

What this means is, over 3,000 hydropower dams and diversions are either in development or proposed, with another 1,003 already in existence. Activists and local communities say the dams cause irreversible damage to the wildlife and the people who live in the region.

So far the Vjosa has remained untouched, but there are 38 more proposals for hydropower dams in the works.

“Hydropower projects will completely and irrevocably destroy this unique river ecosystem,” explains Theresa Schiller, who coordinates the ‘Save the Blue Heart of Europe’ campaign at EuroNatur. “Hydropower doesn’t deserve the notion of being ‘green’, as it is always at the expense of biodiversity in riverine landscapes.”

A 2012 study which examined the 35,000km of Balkan rivers reported that dams have “a significant impact on the river ecosystem,” while also threatening the “wild terrestrial animals, including large carnivores, living in mountain fringes.”

The report’s authors added that dams in the region would lead “to a loss of ecological integrity, river degradation, and consequently a decrease in biodiversity.”

Studies released last year showed that the two of the main proposed hydropower projects on the river could lead to both economic damage and ecological degradation, with severe ramifications for Albanian agriculture and tourism.

A two-year sediment assessment found that by damming the river, the flow of sediment to the coast by the Vjosa would be impeded. This means that the reservoirs would fill up with sediment within 30-60 years.

“Due to the high sediment transport rates of the Vjosa, modelling shows an annual reservoir loss of about 2 per cent in the case of Kalivaç and even more than 2 per cent in the case of Poçem,” explains Christoph Hauer from the University of Natural Resources in Vienna.

“This is more than double the global average of annual storage losses, considerably reducing energy production starting from year one of operation.”

As a result of this sediment build-up - the efficiency of the dams will be enormously hindered. So for activists, the moderate benefits of hydroelectric energy don’t even begin to outweigh the severity of the damage these projects will cause.

Across the entire Balkan region, it’s believed that 91 per cent of planned dams will provide very little energy (less than 10MW capacity). But the ecological damage they can cause is unknown, as there have been so few environmental impact studies carried out for projects of this size.

“They put the river into the pipe, they channel it into a flow for power and for kilometres they dry the river completely,” says Mihela Hladin Wolfe, director of environmental initiatives at Patagonia. The brand released a documentary called Blue Heart about the cause in 2018, and has been supporting activists in the region over the last few years.

“They change the whole water scheme of the region. Hydro is an old technology. There are lower impact energies out there. Nature is slowly disappearing because of the decisions we are making.”

A continent-wide campaign

The Save the Blue Heart of Europe campaign exists to safeguard this vital territory. Over the last few years, along with a high profile partnership with Patagonia, the group has worked to connect organisations and activists in countries throughout the Balkan region and Europe long-term.

The campaign concentrates on four key areas: the Vjosa River, Macedonia’s Mavrovo National Park, the Sava river in Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia, and the rivers of Bosnia and Herzegovina. All four are under threat from dam projects, but as the campaign continues to gain traction and widespread awareness, there have been wins.

In 2017, Albania had its first environmental lawsuit. Campaigns filed to prevent the construction of a dam in the Pocem gorge. The group won and the project was scrapped, but appeals against the decision are still ongoing.

The European Parliament has even begun to take notice of the continual struggle in the region, and in 2018 publicly called on Balkan countries and the European Investment Bank (EIB) to stop funding hydropower projects in protected areas.

But these wild waters are still at risk of being tamed, as governments and companies seek to profit off hydropower - but campaigners aren’t giving up the fight. So how long does the Blue Heart of Europe have left?