What happens before the warning even arrives may be the most important part.

Early warnings save lives. Tens of thousands of them over the past century, according to the World Meteorological Organisation.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

As they’ve improved, the number of deaths from weather, climate and water-related events has dropped dramatically since 1970.

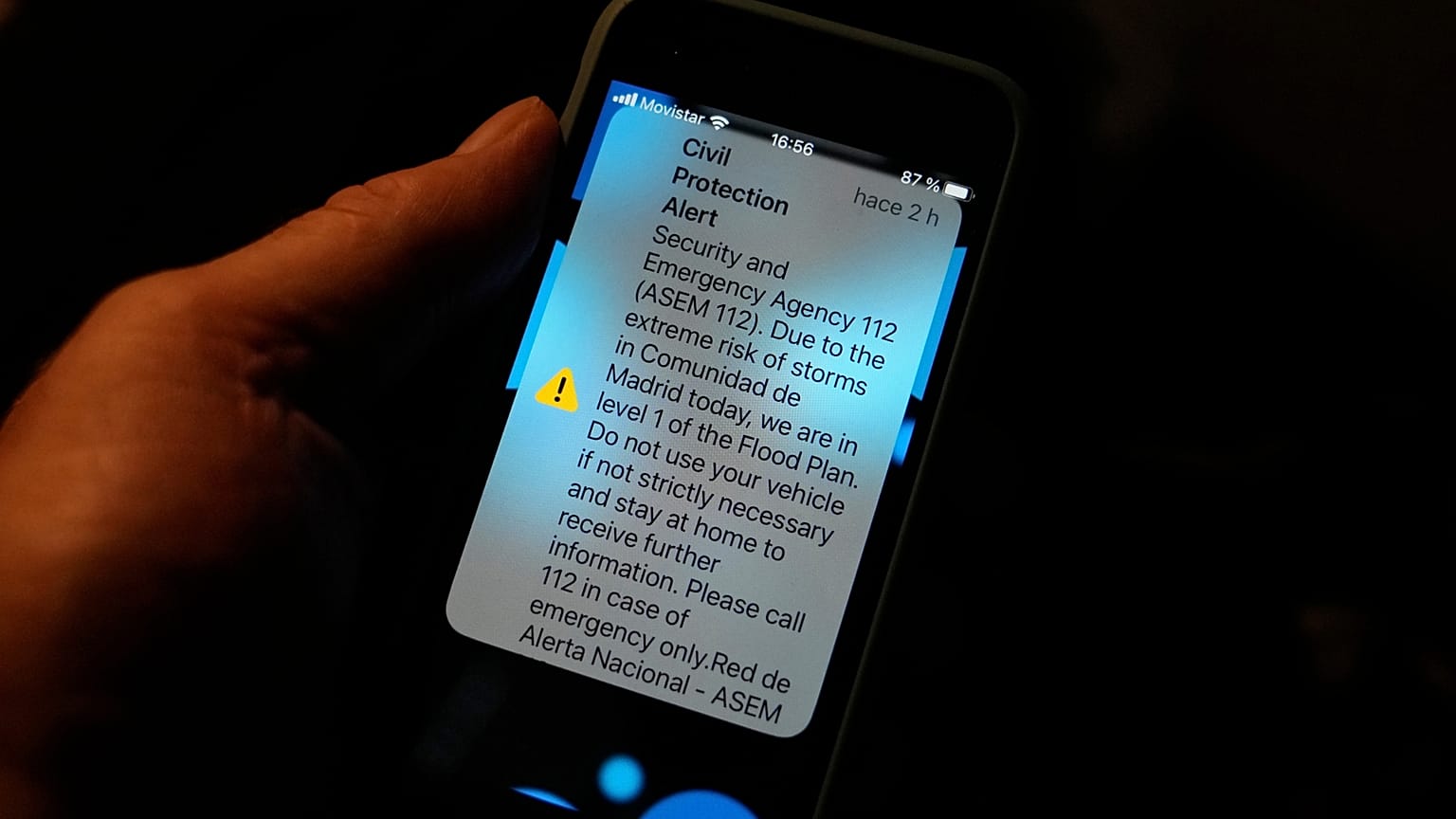

With extreme weather increasing in intensity and frequency, they are more important than ever before. France sent its first-ever emergency weather alerts during storms in July this year. In September, Spain used its mobile phone alert system for the first time to warn people about the risk of flooding in Madrid after record rainfall.

But, as countries across Europe test and update their systems, what exactly does an effective warning look like? And with so much riding on their efficacy, could our alerts be better?

It is a lot more complicated than simply making sure those in danger receive a message, according to Lars Lowinski, a Severe Weather Expert from WetterOnline.

How do we get warnings about extreme weather?

In the past, warning systems for a variety of emergencies - from bomb threats to extreme weather - relied on sirens to get the message across. Many systems were removed across Europe in the 90s after the Cold War because it was thought that they weren’t needed anymore.

“If you go somewhere like Devon or Cornwall where you might still get flooding, sometimes potentially even life-threatening flooding, there aren't any sirens,” Lowinski explains.

“So what are you going to do? You need some other platform to get your message across and to tell people that they might be in danger.”

There are plenty of ways to do this from TV broadcasts to radio or even social media - essentially, all the channels we use to communicate with each other on a daily basis.

Methods like mobile broadcasting are now widespread too. Vital information is sent directly to our mobile phones, often accompanied by a special ringtone and vibration.

Around 95 per cent of the world’s population has access to mobile networks and 75 per cent own a mobile phone. With one message you can reach hundreds, thousands or even millions of people in all kinds of emergency situations.

How does weather warning technology work?

The technology behind these warnings is simpler and more direct than you might think. The alert messages work a lot like driving through an area and tuning into a local radio station, Lowinski says.

“It uses technology that [means] as soon as you are within reach of a particular phone transmitting station or a phone mast, you're going to get that signal,” he explains.

“I can define, say, a radius of people in West London. If there's some sort of risk, some sort of hazard, then I can just draw that polygon and say that everyone within that polygon is going to receive that message within the next 10 seconds or 20 seconds.”

It's like a siren but with much more information attached. The real challenge, it turns out, is getting people to understand what that message actually means.

“A forecast or warning is only of value if the recipient of that information understands it and takes the right action,” Lowinski adds.

How do you get people to act on weather warnings?

Communicating the severity of the threat and the next steps people need to take can be the hardest part of creating an effective warning system.

“Even a theoretical forecast that is 100 per cent correct isn’t of much value if we do not describe the impact,” Lowinski says.

“We need to create an effective message that also tells people how to prepare.”

That information, he explains, needs to be easy to understand and relatable to people’s lives. A notification that tells you there will be 110 to 120 km/h winds doesn’t mean much if you have no idea what that actually looks or feels like.

“Is that dangerous or not? Is that typical for my area? Is that something I've experienced before? That's the sort of information where we need to make some improvements,” Lowinski says.

What good communication of threats entails varies depending on where you are in the world and who you are as a person.

Someone in Germany doesn’t have the same life experiences as someone in the US, Brazil or India. A keen weather enthusiast may need less information than someone who looks at the forecast purely to know if they need to grab an umbrella that day.

“There’s a couple of days every year or maybe just one day when they are on holiday, for instance, where dangerous weather might have a huge impact on their lives,” Lowinski emphasises.

“And that’s when we need to be able to tell them directly what’s going to happen so that they understand it and take the right action.”

When done well, weather warnings are life-saving on a massive scale. Southern Bangladesh is extremely vulnerable to storm surges and high winds - particularly in exposed areas without the resources to defend people.

When recent cyclones hit Myanmar and Bangladesh, effective warning systems meant millions of people could evacuate.

“That was something that would have been terrible even 20 years ago in terms of the death toll,” Lowinski says. “We have had events in the past where that was the case because they didn’t have the warning system in place, but now they do.”

Why do some weather warnings fail?

One such event occurred in Europe as recently as 2021 when a lack of effective emergency communication led to deadly disaster. Record rainfall across western Europe caused flooding in Germany and Belgium that killed more than 200 people.

Germany’s National Weather Service put out appropriate purple level warnings - the highest on the country’s four-tier scale. To some extent, it was clear that a serious event was about to occur but the reality of what was going to happen was difficult for people to comprehend.

“The thing is that, even though there were warnings, many people in the affected areas were not aware of the danger until it was too late,” Lowinski explains, “even though we had those severe weather warnings in place, sometimes three days in advance.”

The official weather warnings may have been too focused on numbers, he says. How many millimetres of rain the region would get in 48 hours, for example. In some areas, layers of bureaucracy also delayed the notification process.

People struggled to understand the danger in real terms compared to the flooded basements or roads that they may have already experienced.

Lowinski says it failed to drive home the message that this rainfall would be “different and dangerous”.

What can Europe learn from other countries’ warning systems?

“There's still a lot of work that we need to do in Europe, not just in Germany, but in many European countries,” Lowinski says. And there are many global examples to draw on.

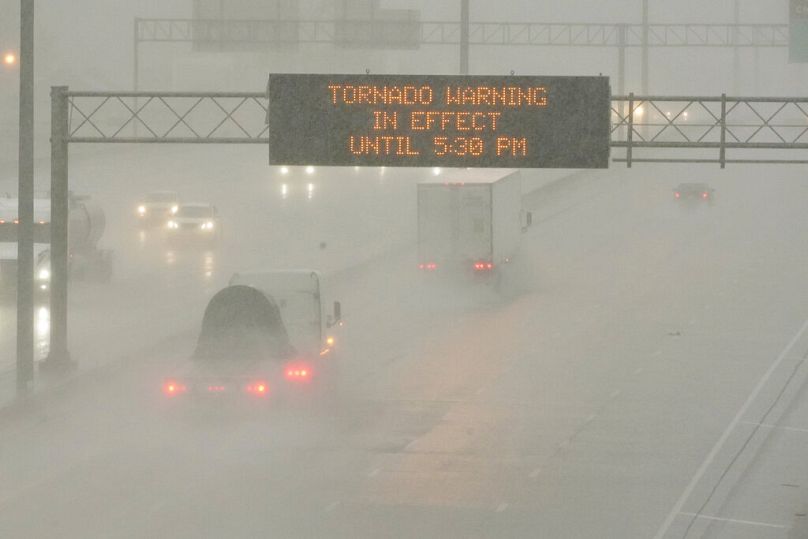

The US has an effective system for disseminating easy-to-understand information when extreme weather events occur. Social science studies have been used to improve the information sent by the nation’s Wireless Emergency Alert (WEA) system.

These alerts are only sent in the event of extreme weather. A similar system is being planned in Germany where warnings will be sent to people’s phones when the severity reaches the highest level in the four-tier warning system - an attempt to differentiate extreme weather.

WEA alerts translate scientific jargon into everyday language that everyone understands, which gets them to act. TV broadcasts and social media posts use practical representations of weather impacts like 3D animations of flooding to visualise the threat.

“One aspect is good forecasting, but the next aspect is good warnings and good communication of the impacts. The third aspect is awareness, and that's something that needs to happen way before the severe weather strikes.”

Effective warnings start before extreme weather strikes

In the US, this comes in the form of awareness weeks for events like hurricanes, severe thunderstorms and tornadoes. What you need to know about the impacts and how to be prepared is covered across schools, TV reports and events.

“We could do something similar in Europe with floods, for instance, because floods are a big issue in most European countries; or wildfires in areas that haven't seen wildfires in the past,” Lowinski says.

In its own weird way, climate change and widespread news coverage of the crisis are also helping to drive home the message.

“I think climate change is kind of helping us a bit because there's an increase in awareness that weather sometimes can be dangerous and at least a couple of times a year,” Lowinski says.

“I think that's something that wasn't there even five or ten years ago. It’s a positive side effect of the climate change discussion.”

The challenge now is to use all of these tools at our disposal, from mobile broadcasts to social media, local news and education to spread effective warnings that can help save lives when extreme weather hits.