In the lead up to this year’s Global Climate Strike, Europe’s climate researchers share the changes they have seen.

This year’s Global Climate Strike on 15 and 17 September marks the fifth anniversary of the movement started by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

2023’s demands include divesting from new and current fossil fuel projects, sharing the burden equally among society, investing in community-owned renewable energy projects, and paying reparations to communities affected by the climate crisis.

The protests, organised by the Fridays for Future group, have seen rapid growth. According to their figures, some 27,000 people across 150 countries took part in the first strike in August 2018.

By the next year, around 3.8 million people took to the streets across 3,800 cities in what is considered to be the single largest climate protest ever. The real number is likely higher, as Fridays For Future may not receive all attendee estimates from local organisers.

The protests are not just reaching politicians. Researchers throughout Europe are motivated by the strikes: to both take part and further their own work in the lab.

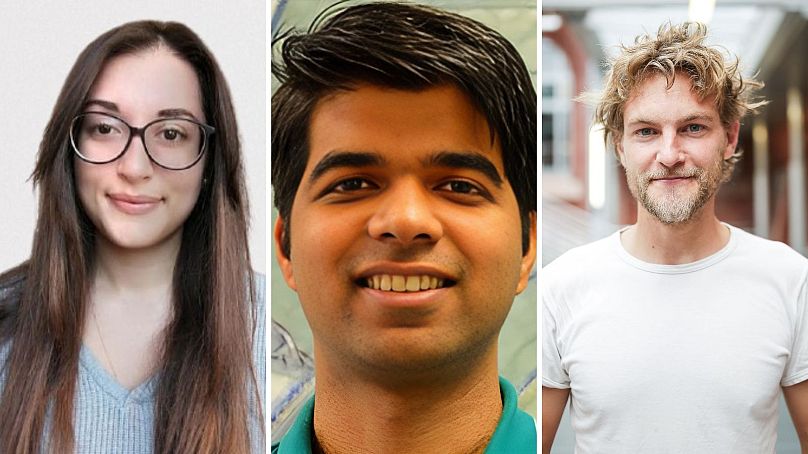

In Vilnius, Lithuania one of those protesting was behavioural scientist Audra Balundė, now head of the Environmental Psychology Research Centre at Mykolas Romeris University.

“My motives were very simple,” she says. “I just wanted to support young people’s efforts and to show what I stand for. It seemed the right thing to do.”

As elsewhere, the protesters were demanding the government do more to curb pollution and make sure that the most vulnerable are not abandoned to the worst impacts of climate change.

Why do scientists join climate protests?

Audra says that she also wanted to add her voice as a scientist to the strikes.

“It seemed important to show to those who might feel tempted to marginalise protesters - especially young ones by downplaying their requests because of their young age - that researchers stand together with protesters and support their action,” she says.

Attending the protests also motivated Audra to continue her research, which includes exploring how people’s morals and sense of identity affect how they conserve the environment.

She is also working with an EU-funded project called Biotraces to find more socially-inclusive ways to boost local ecology. For example, by looking at what could prevent local communities from accepting river restoration projects in their residential area.

Some of her earlier research showed that people’s environmental values, self-identity and their ‘personal norms’ to engage in environment conservation behaviour were related to adolescents' support for climate change activism. Younger generations, in other words, feel a greater responsibility to act for the environment.

Across the continent in Brussels, those personal norms motivated researcher Adalgisa Martinelli to take part in a local demonstration to improve the city’s greenery last year.

Days after she arrived from her native Italy in September 2022, Adalgisa was impressed by a local group’s positive message and specific goals: add more plants and flowers to the city.

“It was not like [people were] arguing or fighting, because I don't like that kind of communication style, but it was very specific,” she says.

The message also seems to have gotten through to local authorities, as Adalgisa says that she has seen a marked improvement of the city’s parks and green spaces. And, she adds, these gatherings also influence other people’s attitudes.

“I see many people take single steps - for example, going to work on foot or taking the bike. That shows the value,” she says.

How effective have the climate protests been?

Working with a Brussels-based think tank, Adalgisa is now part of the ‘Leguminose’ project studying how European agriculture can better use intercropping (simultaneously growing two or more crops in the same field to improve soil health).

A colleague of hers on the project is Ishan Bipin Ajmera, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, Austria.

Like Adalgisa he is a recent arrival to the country and can see how climate protests are leading to clear changes for people.

“It seems that the climate protests have effectively raised awareness and influenced the public discourse on climate issues,” he says.

But in his native India, he describes the effectiveness of climate protests as being “limited or mixed.”

He puts this down to varying public perceptions. Debates in India centre on economic development versus environmental protection, policy challenges, and regions having different reactions to climate advocacy.

Even though they might not pressure politicians in the same way, Ishan believes these debates are still raising awareness. “My parents, extended family, and friends back home often talk about the shifting weather patterns, increasing global calamities or governmental policy measures they hear in the news or debated in public,” he says.

Back in Europe, other researchers know that protests still have far to go and are worried about signs the movement may be losing momentum.

“It makes you feel less alone”

Post-COVID, protest figures remain low. Last year’s strikes saw around 70,000 people participating globally on a single day, though there were fewer attendance reports submitted by local organisers.

“The fact that fewer and fewer people are taking part perhaps shows that there's a resignation on the subject, as if we couldn't do anything more,” says Benoit Durillon, an associate professor in electrical engineering at the Lille Laboratory of Electrical Engineering and Power Electronics.

Like Audra, he took part in an earlier Climate Strike but has mixed feelings about how it went.

“I liked the atmosphere overall, except unfortunately for a few moments of tension with the police, as the French context is already very tense,” says Benoit, who is currently researching how to better balance Europe’s energy grids with the ‘ebalanceplus’ project.

“But above all I like the creativity of the slogans and placards which often show, with humour, that this is a cause that touches people. It makes you feel less alone.”

And the researchers feel the protests are helping them communicate their work with others curious about the points raised by the strikes.

“I have a little sister, and she's asking me more and more for book requests or some articles, because [there’s] too much information [available],” says Algasia. “So of course, I always try to give her some guidelines.”

Even researchers who do not wish to join this year’s protests still have a vital opportunity to share their informed views with others, says Benoit.

“Don't run away from the debate when it comes up in everyday life,” he says. “For me, this is also a form of protest.”