What's the role of volcanoes in climate change? We report from the Spanish island of La Palma and reveal the true influence of the emissions from the Cumbre Vieja volcano on our atmosphere.

The volcano on the Spanish island of La Palma caused widespread havoc for nearly three months, but did its emissions have any impact on Earth's atmosphere longer term? Do volcanoes have a significant role to play in climate change? We set off for the Canary Islands to investigate in this month's episode of Climate Now.

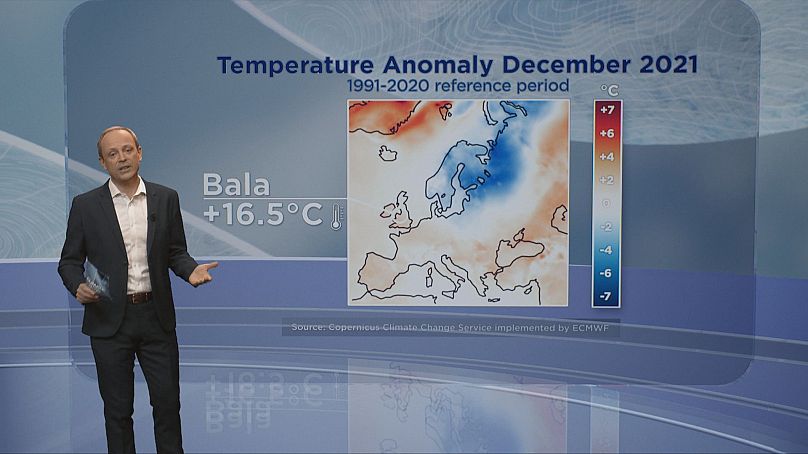

First, a roundup of the latest data for December from the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Sixth warmest December on record

On a global scale, December 2021 was 0.3 degrees Celsius above the 1991-2020 average, making it the sixth warmest December on record.

In Europe there was a striking contrast in temperatures. Western and southern Europe were much warmer than average last month. So much so that Bala in the UK hit a new record high of 16.5 degrees on New Year's Eve. Across Scandinavia, the Baltics and northern Russia it was colder than usual. Sweden had its first colder-than-average December since 2012.

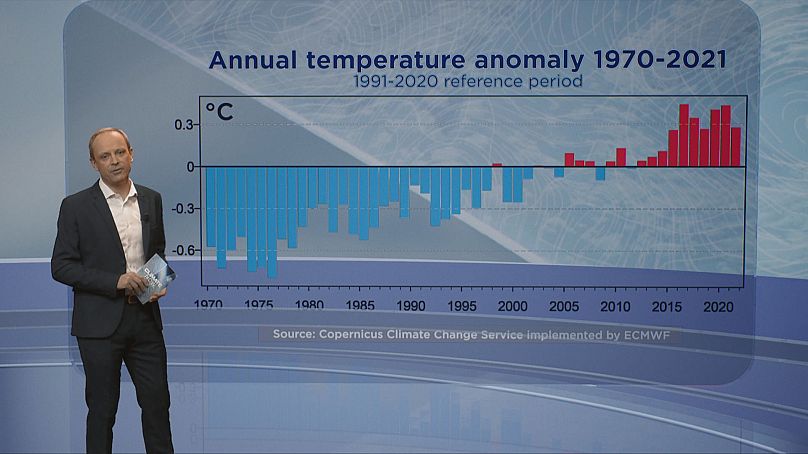

With 2021 behind us we can now say last year fits into the overall warming trend since 1970, with 2021 classed as one of the seven warmest years on record, despite being cooler than the most recent years.

What's the impact of volcanoes on our climate?

Do the gases thrown out by volcanoes have a long-term impact on our atmosphere? Last month, with the volcano eruption in La Palma still underway, we set off to the Canary Islands to investigate.

Volcanologists Ana Pardo Cofrades and Catherine Hayer from the University of Manchester in the UK worked every day since the eruption began in September 2021 to measure the quantities of sulphur dioxide, carbon dioxide and other gases emitted by the Cumbre Vieja volcano.

Pointing to the plumes of white steam rising from the hillside, Cofrades explains: "We have the lower vents there that are just degassing...the gas is coming from the magma. So as long as there's magma down there, there's emission of gases,"

The gases are a danger for people close to the volcano, but overall they have been less of a problem for the people of La Palma than the lava and ash. Three thousand buildings have been destroyed by lava flows, and the fine silicate ash is to be found everywhere - in the air, on the road, on roofs, in gardens, and all over the island's famous banana plantations.

"So we can have structural damage to buildings. We can also get damage to electrical subsystems because the ash is often (electrically) charged," explains Hayer, adding: "We also get acid rain. So around in the local area, we've had real problems with both ash fall and acid rain that's been affecting the banana plantations."

The acid rain is caused by sulphur dioxide, a highly reactive gas emitted by the volcano.

The SO2 can reduce air quality, and in major eruptions it forms tiny particles that can have a short-term cooling effect on the climate.

But what about the carbon dioxide from the volcano? How significant is the greenhouse gas emission from La Palma?

On the island of Tenerife atmospheric scientist Omaira García from the Izaña observatory of the Spanish meteorological service AEMET spotted a spike in CO2 during the eruption:

"Carbon dioxide concentrations have increased very significantly. But it should also be emphasised that it has been very localised, and over a very short period of time," she says.

At its peak the volcano was emitting as much as 3,000 tonnes of CO2 per day. That may sound like a lot, but compared to human emissions, it's tiny: "If we compare this value with, for example, the emissions produced by air transport, which account for 330,000 tonnes per day, the emissions from a volcano as small or medium-sized as La Palma can account for one hundredth of the emissions from the aeronautical sector alone. It is absolutely negligible," says García.

In fact, if we combine together all the CO2 emitted by all the volcanoes worldwide then the total represents under 1% of the total emissions from anthropogenic sources such as heavy industry and transport.

Volcanologist Ana Pardo Cofrades sums up by saying: "The volcanoes have been around for longer than we have been. And climate change didn't start until the industrial revolution. So I don't think we can blame the volcanoes about this climate change."