Greenpeace says we shouldn't be spending money on tech that keeps us "locked into the fossil fuel era".

In the race to contain the climate emergency, governments worldwide are scrambling to cut carbon emissions. From encouraging people to walk instead of drive, to planting millions of trees, the aim is to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But some are planning to put them - yes, the actual CO2 emissions - into the ground, using a form of technology called Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). This allows us to trap up to 90 per cent of the CO2 that would normally enter the atmosphere, under our feet.

How does it work?

Capturing carbon and storing it is a complicated process, but promises massive pay-offs in the long run. So what does the process involve?

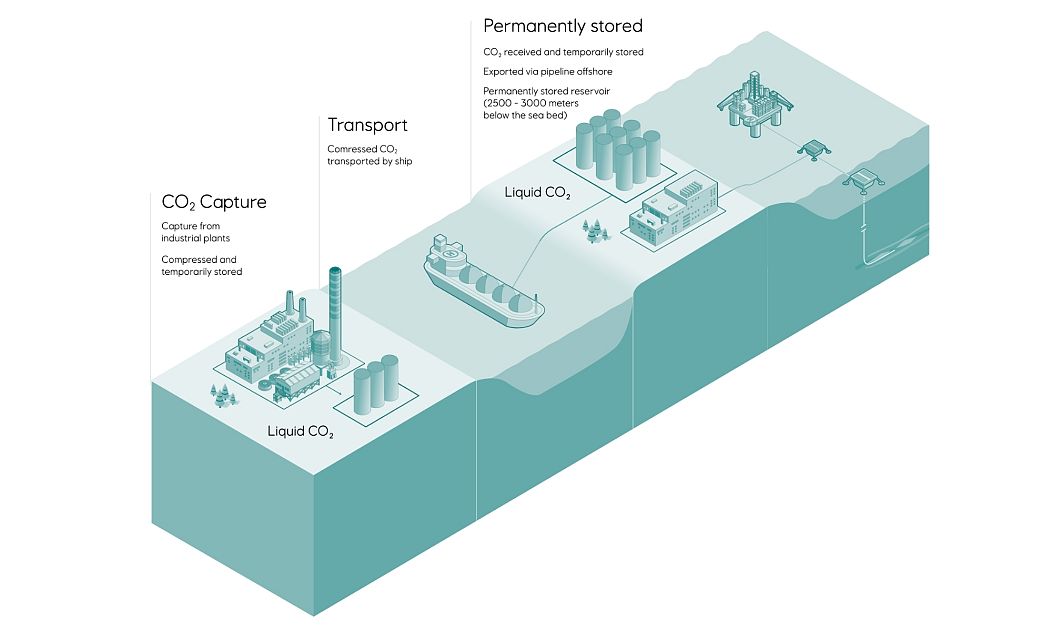

Put simply, emissions are injected into an absorber that contains a solvent which collects the CO2, while other components are released in the air. The captured CO2 is then separated by the solvent using heat, so it can be transported by pipeline or ship and placed in underground geological formations, such as oil and gas reservoirs, unmineable coal seams and deep saline repositories.

This procedure is employed to limit the impact of heavily polluting plants such as fossil fuel power stations, as well as industries producing cement, iron, steel and chemicals, as it’s difficult to find eco-friendly alternatives.

Aside from being stored, the carbon can also be repurposed and sold to third parties, which is an even bigger bonus. This is often called carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS).

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the vast majority of CCUS projects have so far supplied fossil fuel companies for enhanced oil recovery (a way to boost crude output in oilfields), but the CO2 could be employed to produce synthetic fuels, chemicals and building materials.

A somewhat unpopular choice

Currently, the world is able to capture 40 million tonnes of CO2 a year, which equates to 0.1 per cent of 2019’s global emissions. The Global CCS Institute says the available capacity needs to increase more than a hundredfold to make a difference and reach net-zero by 2050.

Although the idea has been around for a while, the technology is relatively new and its high costs have proven unpopular. Since gas from coal or gas-fired power plants has relatively low concentrations of CO2, it takes extra energy to capture it, which makes it pretty pricey.

Governments have never provided incentives until recently. The US - the current world leader with a mere dozen projects - decided to change that only two years ago when it set up a tax relief.

It was perhaps the Paris Agreement that pushed governments to adopt CCS, as they had to step up efforts to limit pollution.

Existing and future projects

As of 2020, there were 26 commercial CCS facilities in operation globally, although all outside the UK or the EU, with three under construction and 34 in the design process.

Plans for more than 30 new integrated CCUS facilities have also been announced since 2017, for a total investment of more than $27 billion (€22 billion). The EU Commission has granted €102 million to the Porthos CCUS project in Rotterdam, alongside a total of €33 million for five other CCS projects approved last October.

Among these there is also the Northern Lights project, which has a price tag of €670 million. Last month, the Norwegian government announced it would fund 80 per cent of it.

Developed by energy giants Equinor, ENI and Total, it will hold up to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year, with potential to reach 5 million, in a reservoir placed 2,600 meters below the seabed of the North Sea.

The carbon, captured from a cement factory and a waste-to-energy plant in the Oslo-fjord region, will be transported by and injected from purpose-built ships.

Environmental concerns

But many environmental groups aren’t happy about CCS and CCUS, which they say are not deemed an effective solution for the climate emergency.

According to a report by climate change research centre Tyndall Manchester, 81 per cent of carbon captured to date has been used to extract more oil via the process of enhanced oil recovery. This means that CCS is mostly used for carbon-emitting oil extraction that wouldn’t have otherwise been possible.

“[It] is a technology that is quite unproven and is very expensive,” Sebastian Mang, climate policy advisor at Greenpeace European Unit, tells Euronews Living.

“We are not sure whether these carbon storage facilities will actually, for the long term, capture carbon. How long will those be viable, will there be leakage, how much leakage? All these questions about the long term effects of storing human-produced carbon underground, what impact will that have?”

Mang adds, “we should really focus on transitioning the economy to clean solutions such as renewables and efficiency, rather than spending money on technology that keeps us locked into the fossil fuel era.”

These concerns are echoed by Global Witness, which noted that CCS has been discussed for over four decades but never took off properly.

“It is perverse that the world's biggest polluters are in fact using CCS to extract more fossil fuels, creating more emissions,” states Ken Penton, climate campaigner at the organisation.

“The time has now come for governments to stop chasing the CCS unicorn and instead build vibrant renewable energy sectors and massively increase energy efficiency of homes and businesses. The best and most proven way to stop climate change is to keep fossil fuels in the ground.”