What are marine heatwaves? And how are they impacting on the previous havens of biodiversity that are corals in areas such as the Medes Islands? Climate Now investigates the serious consequences of the phenomenon for ecosystems in the Mediterranean.

In this episode of Climate Now, we visit Spain to witness the damaging effects of marine heatwaves on life below the waves.

But first, the latest climate data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Temperatures for August

In Europe, August was warmer than average, with temperatures 1.1 ºC above the 1981-2010 reference period.

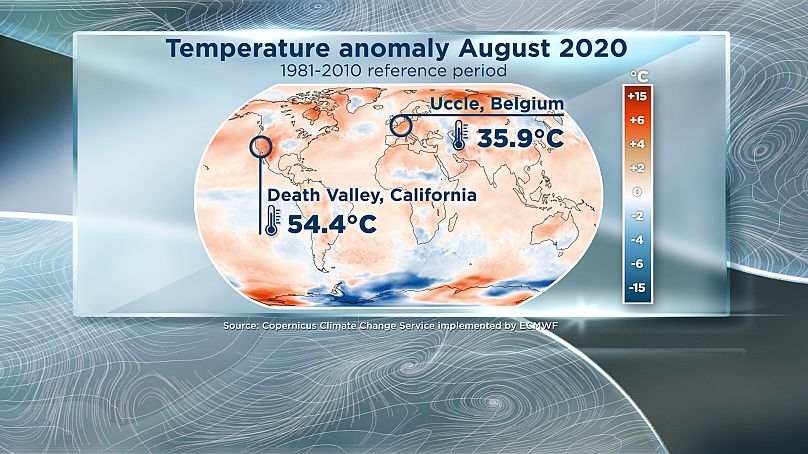

The map of surface air temperature anomaly below demonstrates some of the big trends for the month; it was much warmer than average in north western Siberia, cooler in western Russia - and warmer over much of Europe; on one day in the Brussels suburb of Uccle, the temperature reached 35.9 ºC , a record for August there.

In the western United States, it's been much warmer and drier than on average, including what may become a new world record for the month of August anywhere on the planet, with a temperature of 54.4 ºC in Death Valley, California.

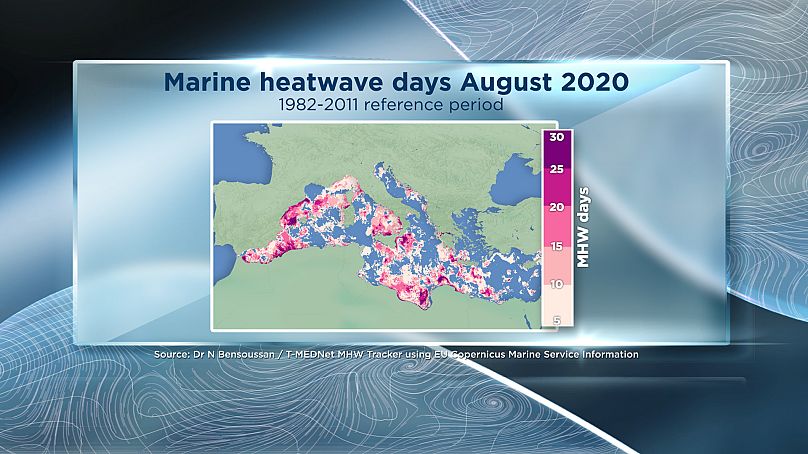

The below graphic explains the concept of marine heatwaves; these are days when the water temperature is 2, 3 or even 4 ºC higher than expected - for a period of at least five days.

The graphic shows the number of marine heatwave days across the Mediterranean in August.

It's clear that the areas around Italy, Libya, Morocco, Spain and Algeria were particularly affected. The coast of France meanwhile is free from MHW events because of the cooling effect of the mistral and tramontane winds.

Marine heatwaves are generated by warmer weather, just as heatwaves are on land. Because of climate change, they're becoming more frequent, more intense, and they're lasting longer.

How marine heatwaves hit gorgonian communities hard

Marine heatwaves can have a devastating effect on marine ecosystems, especially on creatures like corals which are havens of biodiversity.

To find out more about the problem, Euronews visited the Spanish region of Catalonia and the Medes Islands.

Marine biologist Joaquim Garrabou regularly dives around the islands, which are near the resort of L'Estartit, as part of his research. The islands have been a Marine Protected Area since 1983, making them an ideal spot to observe the effects of marine heatwaves.

Fifteen metres below the surface, Joaquim observes a population of gorgonians, a variety of soft coral, that is dying out because of higher temperatures:

"What we are going to do basically is count how many colonies are unaffected and how many colonies are affected by mortality.

"Normally in populations that are well conserved, you would have around 5 to 10% of colonies affected by mortality. And in this population in recent years we have seen the rate of colonies affected at more than 80%."

Joaquim's survey immediately identifies dead gorgonians in areas which were full of life a decade ago. The water at the depth Joaquim is investigating should be between 19 and 22 ºC, but on the day of the dive, it's at 23 degrees. Furthermore, there is evidence of mass mortality impacts on the gorgonians down to 40-50m depth.

The Medes Islands have recorded 30 heatwave days in total since July 1st this year. The record surface temperature recorded here stands at 26.3ºC in August 2019 - more than 3ºC above the climatic mean (1974-2019)

The average temperature in the Mediterranean is rising around 0.4 degrees per decade, which is a serious issue in itself; but these heatwaves are the most pressing problem. For the most part, the corals just aren't adaptable enough to survive.

Joaquim says that the upper threshold of tolerance for these species of gorgonians is around 24-25ºC :

"Periods of exposure to temperatures above these limits cause physiological stress and greater virulence of possible pathogens. This is what ends up causing the mortalities that we've observed."

Marine heatwaves are harming ecosystems around the Mediterranean and beyond, with kelp forests and coral reefs from Australia to California also suffering.

Joaquim says that even in a scenario where the tide is turned on global warming and temperatures start to come down, these colonies could take over a century to recover:

"These species are long-lived; they can live for hundreds of years and therefore the loss of these colonies will take as many or more years to recover in the future," he concludes.