One of Igor Mitoraj's most spectacular works, the monumental sculpture "Tindaro", went under the hammer this week at the Polswiss Art Auction House in Warsaw and fetched a record-breaking €1.6 million. This historic return has sparked a renewed interest in the artist and his reflective works.

The work of Polish artist Igor Mitoraj has fascinated both critics and audiences around the world for decades. His monumental sculptures, often depicting fragmented bodies and faces, evoke ancient traditions, but at the same time reference concerns still found in the contemporary world.

"I think this is a breakthrough, a moment when Poles are rediscovering Mitoraj. I am very curious to see how far this fascination will go. But for me the most important thing is that we are bringing Mitoraj back to Poland," Mitoraj's biographer Agnieszka Stabro tells Euronews.

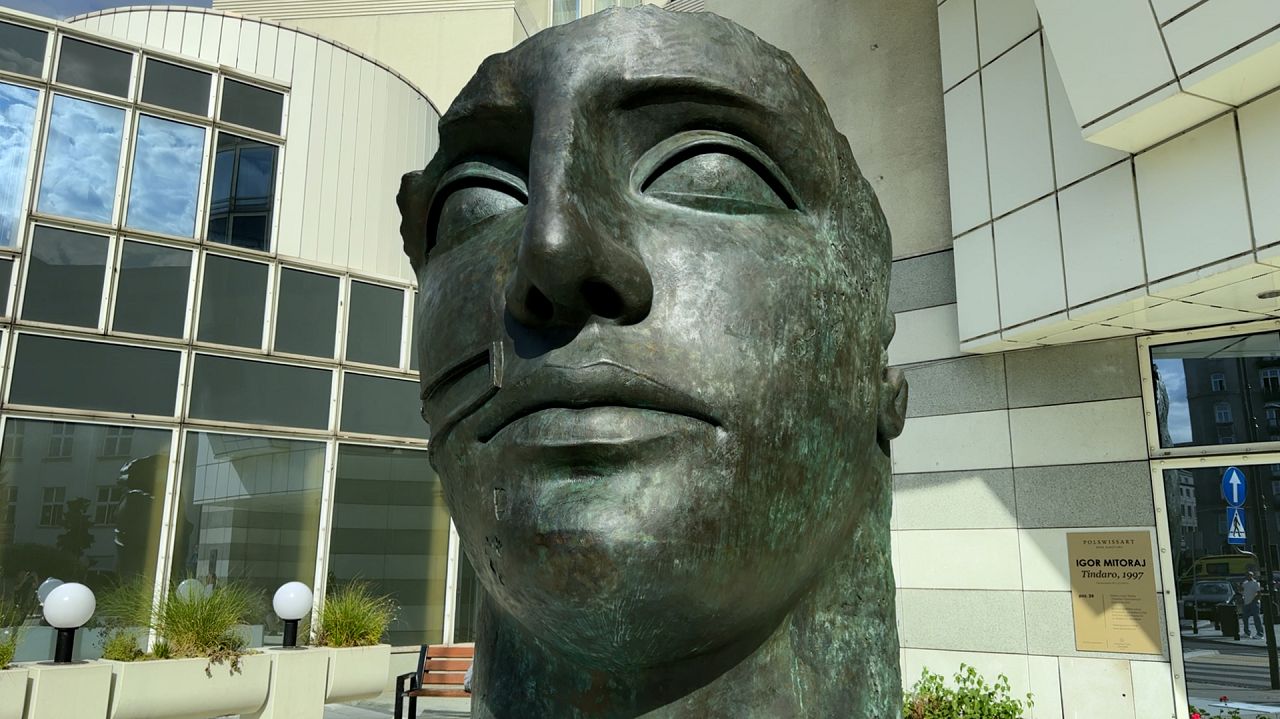

'Tindaro' - the return of monumentalism to Poland

"Tindaro" is a monumental bronze cast of the head of a young man. It stands over four meters tall, was created in 1997 on the orders of the international consulting firm KPMG. It originally stood in front of the company's French headquarters at La Défense, the modernist business district of suburban Paris. For some twenty years, it formed an integral part of this distinct architectural landscape.

The work is one of Mitoraj's most impressive creations: not only in terms of size, but also form - the back of the sculpture contains two pillars connected by a beam, reliefs, a mascaron alluding to the "Mouth of Truth" or "Bocca della Verità", an ancient Roman mask with an enduring medieval myth. According to legend, liars who place their hands inside the marble mask will have their hands bitten off.

"Tindaro", therefore, is more than just a portrait. Rather, it is also a structure in which the sculpture builds a dialogue with other time periods, cultures, and artists.

The name "Tindaro" also embodies this symbolism - it refers to the figure of Tyndareos, King of Sparta and father of Helen of Troy - yet another mythological reference, which is often present in the artist's work.

Bringing "Tindaro" from Paris to Warsaw is not just a commercial transaction - it is a cultural event that allows residents and the public to interact with monumental sculpture on a daily basis, building a local context for reflection on cultural heritage, beauty and time.

A life intertwined with art

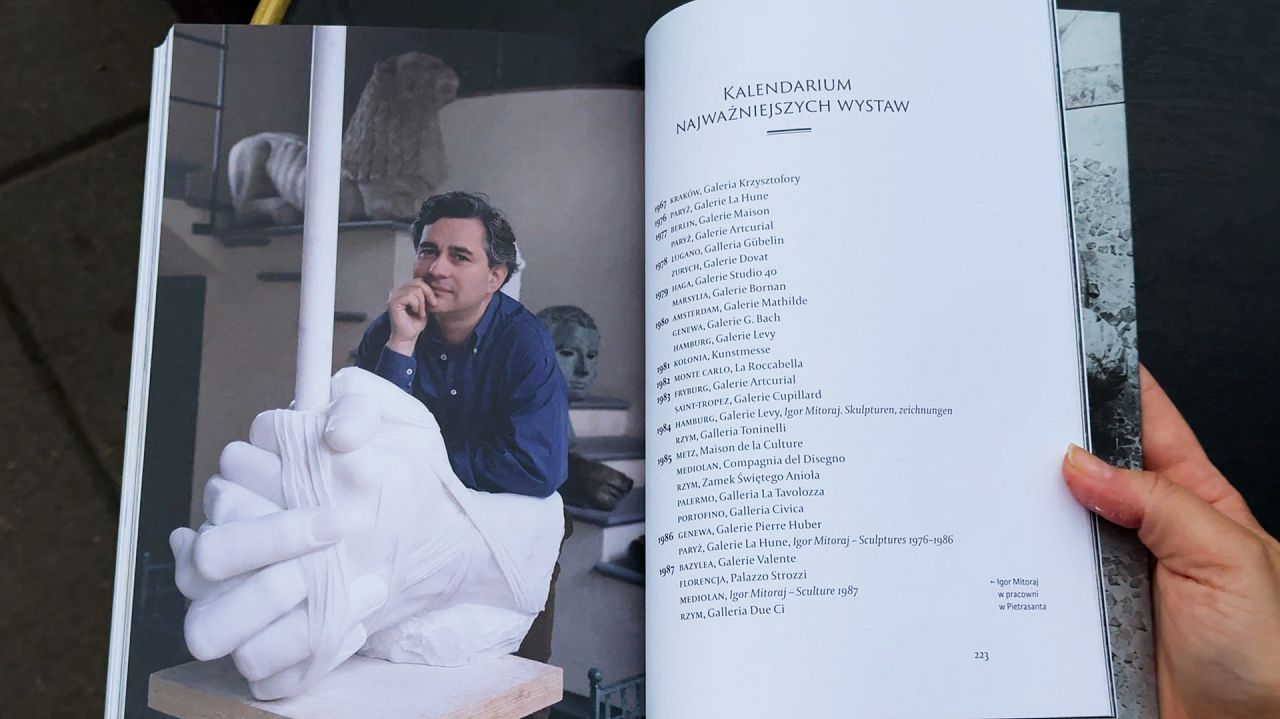

Igor Mitoraj was born Jerzy Makina on the 26th of March, 1944 in Oederan, Germany. His mother was a Polish woman forced to work in Germany, his father a French Foreign Legion soldier, also of Polish origin.

After the war, he and his mother returned to Poland. He spent his childhood in Grojec near Oświęcim.

Mitoraj studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków under famed artist and film director Tadeusz Kantor. In 1968, he left for Paris, where he continued his education at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Initially he worked in painting and printmaking, but later - after many international trips, including to Mexico - he began to work on sculpture. In 1979 he visited Carrara, then in 1983 he set up a studio in Pietrasanta, Italy, a region known for its marble quarries and sculptural tradition.

He died on 6 October 2014 in Paris; however, his atelier, works and legacy live on, and in public places around the world his sculptures are a recognizable symbol of the nexus between the classical and modernist movements.

A 'citizen of the world' who never forgot his Polish roots

The artist's biographer, Agnieszka Stabro, emphasizes that Mitoraj was above all a "singer of beauty" and an artist who "brought ancient culture closer to Poland and Europe". Although he spent most of his life abroad, his art always carried traces of his wartime childhood experiences and the spirit of Polish melancholy.

Born in Germany, he spent his childhood and youth in Poland, not far from Auschwitz.

"The proximity of this place, its history, the atmosphere of the post-war period - all this had a huge impact on his [artistic] sensitivity," Stabro notes. Under the tutelage of Tadeusz Kantor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, Mitoraj learned to perceive beauty as something that is not obvious, but moving.

Although he travelled extensively - from South America to Asia - Europe was his home. Two homelands in particular have marked his path: France and Italy.

He spent 20 years in Paris and then settled permanently in Tuscany, in Pietrasanta, near Carrara - known for its marble that has been used for artistic works for centuries, including by Michelangelo.

"He ended up there by chance, looking for a foundry. But once he saw the town, he fell in love with it. Pietrasanta had everything: marble, tradition, traces of Michelangelo and that Italian sun he loved so much," Stabro emphasizes.

The lifestyle in Tuscany, its lightness and joy, suited the artist more than Polish everyday life. "In private conversations, the people of Pietrasanta told me that he just loved the sun and the weather. But I think it was not just the climate, but the whole atmosphere of Italian life," notes the biographer.

"I think this is an example of an artist in whom life and creativity are inextricably linked," she adds.

His characteristic style is that of monumental sculptures, often fragmentary - heads, torsos, missing limbs, cracks, bandages - all deliberate means of expression. Mitoraj draws on mythology, antiquity, but didn't rely on cheap copies: his works are a dialogue with the past, memory, time and transience.

His art has become a metaphor for life - on the one hand monumental, referring to classical proportions, on the other - wounded, incomplete, revealing the fragility of human fate.

Reflections: beauty, transience, fragmentation

Mitoraj used to say that art should intrigue - not reveal everything at once, leave room for discovery, for mystery. In "Tindaro", this effect of creating a dialogue between viewer, form and space is particularly strong. The monumental head, but also the rear structure is a sculpture "in sculpture".

The pillars and reliefs force the viewer to go around it, to approach it from different sides, to look at it from various angles.

"It is also a bit of a metaphor for life in general, that everything has two sides, nothing is black and white. It's worthwhile to search precisely, not to stop at the surface of reality, but to look further," explains the biographer.

The artist was keen to draw on antiquity and Greek mythology, but the sources of his fascination with monumentality should also be sought in Aztec culture.

Mitoraj was keen to weave ancient motifs into his works, including the mythological Medusa. "Medusa appears in his work very often and has various meanings - sometimes as a symbol of female strength, sometimes of justice and honour. Nothing in his sculptures is accidental. Every detail has a meaning," Stabro points out.

Another of his trademarks is the mouth - repeated in almost every sculpture. "They are the mouth of the artist, a kind of signature," says his biographer.

Art historians often stress that Mitoraj's sculptures are not only a formal experiment, but also a metaphor for the human condition. Missing arms, veiled eyes or cracked torsos become symbols of the fragility of civilisation, loss of identity and cultural memory. This fragmentary artistic language is sometimes compared to archaeological excavations - as if Mitoraj were creating "ancient ruins of the future".

Contemporary artists and critics describe his works as "monumental and intimate at the same time". Monumental, because they often dominate urban space, such as the famous "Testa Addormentata: in Pietrasanta, Italy, or "Eros Bendato" in Kraków. Intimate, because each of these forms hides silence, reflection and melancholy - something that brings them closer to religious or philosophical contemplation.

"He created his own universe," says Stabro, "these sculptures correspond with each other, creating a Mitoraj world where beauty meets frailty."

"Michelangelo is a figure whose footsteps he actually followed and whose traces in Pietrasanta can be found at virtually every turn," she adds.

Critics compared him to Auguste Rodin, pointing to his inspiration from the Italian masters but, as Stabro notes, his strength lied first and foremost in his originality. "It is difficult to compare him to anyone. Yes, you can find traces of influence, but he always created his own language. It is this originality that makes him a postmodernist - because he broke the classical pattern, made his own changes and searched for new meanings."

'Tindaro' will remain in Warsaw

Although the most expensive sculpture in the history of the Polish auction market remains Magdalena Abakanowicz's work "Tłum III" [Crowd III] (1989) which fetched just over €3 million in 2021, the sale of Mitoraj's sculpture is equally significant.

According to the Polswiss Art Auction House, "Tindaro", which stood on Three Cross's Square at the beginning of September, will remain in Warsaw's urban space.

Where? The answer to that question so far remains unknown.

Until the end of September, the sculpture can be seen in front of the entrance to the Sheraton Grand Hotel in Warsaw.