The world's first Islamic Arts Biennale is running in Saudi Arabia as the country continues to diversify its interests and increase efforts, some say, to change perceptions. Discover more about Sumayya Vally, the exhibition and the South African woman artistically directing the show.

Changemaker, Pioneer, and One to watch.

These would all be fair descriptions of South African architect Sumayya Vally who can now add artistic director to her growing list of accolades having helped establish the world’s first Islamic Arts Biennale, organised by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Born in Pretoria (1990), Vally co-founded the experimental architecture and research firm, Counterspace, in 2015 and went on to become the youngest ever architect commissioned to design London’s famed Serpentine Pavilion in 2020.

The following year, Vally was recognized in the Time 100 Next list as an emerging leader shaping the future.

This year, Vally has undertaken a new challenge: designing the first ever Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Taking on this role saw her reimagine Jeddah Airport’s mammoth Hajj Terminal – ordinarily known for hosting hundreds of thousands of Muslims making their sacred pilgrimage to Mecca – as a journey through centuries of Islamic creativity.

Euronews Culture spoke to Vally about the Biennale and its mission, the oft-contested definition of “Islamic art”, and the perspective she brings as a young, South African, Muslim woman spearheading such a seminal art event.

Why the need for an Islamic Arts Biennale?

I strongly feel that there is a need to acknowledge that Islamic faith, Islamic practice and Islamic tradition can and should be making a creative contribution to the world.

I have been thinking deeply about this opportunity to create a temporary home, an entirely new physical setting, one which has such a profound significance in the context of the Muslim pilgrim’s journey, in which to invite artists and audiences to reflect on ritual – the sacred, the personal, and the communal.

I think platforms for sharing ideas, pavilions, and biennales, for example, are incredibly important in how they set the tone for the future and how they allow us to project our imaginations into those spaces. To understand that we have the opportunity to make the future of culture and cultural typologies through these voices and perspectives, which reference and resonate with such diverse geographies, is profound.

How do you see the significance of a woman, and particularly a young Muslim woman, being the artistic director for this event, both within the context of contemporary Saudi Arabia and contemporary Islam? What does it mean to you?

My deepest strength is the confluence of lenses through which I see the world - the woman in me, the African in me, the Muslim in me and - these can be seen as limitations (and of course professionally they are), but they are absolutely the reason I see the future of the world and the visions I have for it in the ways I do.

I believe that hybridity is an incredible strength. The biennale foundation team is made up of a cohort of (mostly) strong women, all of whom are around my age and have cultural overlap with my background and upbringing.

It has been incredibly special to see and truly witness the value of our perspectives in putting forth a project that is entirely different – shaped entirely from these authentic perspectives. I think from the experience I’ve had with our team, if the future of culture is indeed in these hands, we are going to see remarkable things happening from here.

How do you understand the term "Islamic art"?

Existing definitions of “Islamic art” often focus on style, tradition, geography, pattern, and geometry. The ambition of this biennale is to build on and challenge these criteria, expanding on the existing canon of Islamic art, and to question the narrative, museological, and artistic practices of this time. Islamic artworks may have surface similarities, but what really unites them is inherent in how they are made, used, and understood.

When we identify great artworks as “Islamic”, we are simultaneously honouring historical traditions by keeping them alive, and contemporary practices by giving them a history. It is important to situate contemporary work in the historical narrative because it is only in context that things can belong.

The works in the biennale are experiential – they put forth an entirely different definition for Islamic Art – rooted in the experiential, the oral, the aural, our ritual practices and the ingredients and infrastructures of gathering and community.

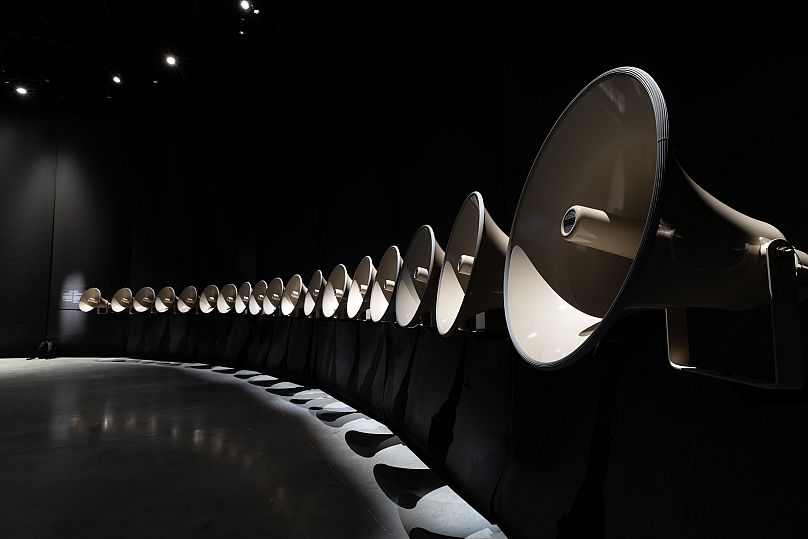

For example, Cosmic Breath by Joe Namy choreographs the adhan, or call to prayer, from 18 different locations, where one wouldn't necessarily expect the call to prayer to be called – a parking lot, a gas station, the side of the road somewhere, from across the world, Japan, Durban in South Africa, Detroit. And he's recorded these and choreographed them so that the call starts at the same time. And this is really reflecting on the idea of cosmic breath, that every second of the day the call to prayer is being called somewhere on Earth. And there are five a day, so when we stand up in prayer, we're joining this undulating rhythm and this undulating call.

So many of our practices are not able to be held in traditional archives because they're not written forms. They're spoken, they're oral, they're passed down from generation to generation, from body to body. Many of our artists are not only taking on these practices and interpreting them in contemporary artworks, but are really deeply inspired by historic objects and historic practices.

In the works curated for this biennale, faith is resonant in the artists’ method of practice, regardless of their own faith or background. For example, the work of South African artist Igshaan Adams, who works collectively, weaving his tapestries together with a group of women from his home community.

The subject matter of his work is Islamic, but there's also something of a meditative nature in the way that he practises, and this repetitive action of weaving is also a kind of spiritual practice. So, we chose artists who have something of a spiritual nature that comes from the faith in their practice.

Who do you see as the main audience(s) for the Biennale?

My hope is that this biennale is an opportunity to invite audiences to reflect on ritual, the sacred, the personal and the communal - to build on that definition and to think through what Islamic Arts means and can mean, for now and for the future. We have seen a true cross-section of Jeddah come to experience the biennale – for many, this is their first experience of art in a setting like this in their own context – we have seen young and old people alike return to the biennale with their families. It has also been very special to witness pilgrims come over from the functioning airport across the road.

I have been avalanched with generous messages from people who came to the opening of the biennale. Many of these messages expressed a wish for the biennale to be in the West so that non-Muslims can access it and learn more about Islam, and see it presented in this way: deeply personal expressions from our artists about our ways of being.

As much as this biennale is an open hand and an invitation for all – east, west, north, south – the power of seeing ourselves represented in this way is also at the heart of the project.

I hope to convey the generativity of Islamic thinking and practice and the diversity and breadth of the Muslim world through the biennale. The philosophies of the Islamic faith offer the potential to think about the future differently. I am thinking beyond the stylistic traditions that have been called Islamic arts, and I have a deep interest in making a contribution to the canon here, to learn from how the philosophies of Islam and how the life of being a Muslim can inspire creativity and creative thinking.

There are an infinity of untold stories, unheard voices to be told, retold, made and remade.