By learning how societies navigated past downturns, students build empathy, critical thinking and resistance to simplistic blame games that fuel the far right and populism — according to a Council of Europe body.

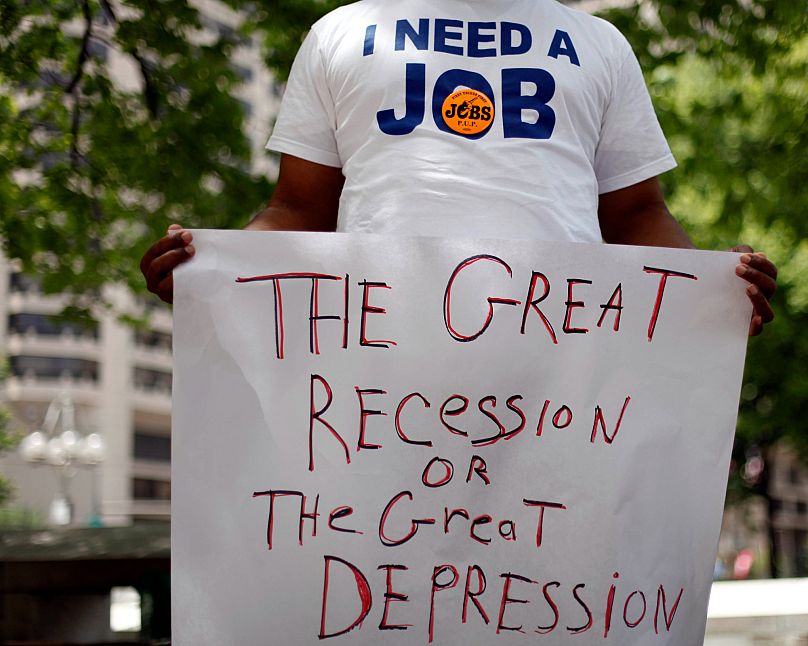

In an era of growing polarisation, rising inequality, and resurgent populism, a new report argues that teaching economic crises in history classrooms is more than a lesson about recessions — it is a lesson in democracy.

According to The Observatory on History Teaching in Europe (OHTE), a platform of the Council of Europe, learning about past economic shocks helps students resist scapegoating narratives and build democratic resilience.

"Crises in public finances and national currencies, as well as rising inflation, have caused continuous or recurring economic instability in numerous European countries, which has been closely linked to rising social inequalities, xenophobia, and the questioning of democratic values," the report stated.

"Teaching about economic crises can offer students the knowledge and skills to resist one-sided and simplistic attributions of blame for economic crises to minorities and stigmatised groups through scapegoating," the OHTE continued.

The report is based on analysis of 17 European countries.

Perceptions of unfair distribution fuel radicalism

The Council of Europe's OHTE was created in 2020 to tackle issues related to history teaching on the continent, as there was previously no centralised body to analyse what was taught in one country versus the other.

This leads to situations where strong populist movements can build up in certain countries such as Hungary.

Teaching about economic inequality, the authors of the report argue, is a crucial aspect of understanding the historical grievances of a country and its effects on politics today.

People who think their society is very unequal are more likely to back populist parties, according to recent analysis published in the European Journal of Political Research.

Voters who perceive strong inequalities in society are about 2.7% more likely to support populist parties, compared to respondents who perceive society as more equal, said the survey.

It added that effects are particularly strong for prominent and large right-wing populist parties such as the Progress Party in Norway, the Danish People’s Party and the Freedom Party of Austria.

People who report financial difficulties are also significantly more likely to support populist parties than those who are financially comfortable, according to findings from a European Social Survey published in 2023.

The ESS identifies this pattern across several countries and survey years, highlighting that felt economic strain — rather than income alone — helps explain openness to populist appeals.

Economic crises teach empathy

The new OHTE report recommends that teachers of economic history should seek to link past events to concrete skills. In other words, don't just "tell the students what the Great Depression was", but rather use the lessons to develop "empathy, openness, cooperation [and] tolerance of ambiguity".

Teachers interviewed for the study reported that when students engage with economic crises historically, they are better prepared to ask “why did this happen?”, “who suffered?”, “who benefitted?” and “is there a scapegoat rampaging behind me?”.

"Exploring such questions can help learners understand that an economic crisis is much more than an isolated economic phenomenon and instead often affects all aspects of societal life," the OHTE report stated.

Economic teaching also allows students to realise that the consequences of crises are heavily dependent on the prevailing political system and the historical period, added the authors.

Classes on economic crises are included in national curricula in all 17 countries studied, and are compulsory in 16 apart from Spain, where including lessons on economic crises is at teachers' discretion.

That alone shows broad recognition of the topic — but reveals little about how the topic is used and framed, and whether there is a general consensus across Europe on how it is taught.

"Economic crises are explicitly linked to the struggle for or against democracy in the curricula of all member states except Georgia and Spain... the French Revolution and the crisis of the socialist economies in the 1980s are the most frequently cited examples, where economic hardship is cited as a driver for mobilising forces to successfully demand democracy," the report explained.

Alternatively, "economic crises leading to the destruction of democracy in various European countries" are usually taught with regard to the rise of fascism and Nazism as a direct result of the Great Depression.

Challenging simplistic narratives

In its recommendations, the report also suggests that economic crises could be taught from the perspective of minority or vulnerable groups. This can be used as a means to subvert extremism-friendly narratives such as “some group did it”, “they always exploit us”, or “the system is rigged by X”, said the authors.

For example, the report criticises the fact that lessons on economic crises rarely focus on specific challenges faced by groups such as the LGBTQ+, Roma, and Jewish communities.

The perspective of women in economic crises is included in six of the 17 countries analysed, but "references to LGBTI history are absent from both curricula and textbooks in all countries". Only 3.4% of respondents to the teachers’ questionnaire indicated that they incorporate LGBTQ+ perspectives into their lessons.

"Economic crises have historically increased the likelihood of stigmatisation and persecution, particularly of minorities (for example, the pogroms against Jews). Roma history is mentioned only in the French curriculum and only 10.3% of teachers reported including this perspective in their teaching," said the report.

Beyond economics — the interdisciplinary gap

There is a key missing piece when it comes to teaching on economic crises in Europe, concluded the OHTE.

While the topic features heavily in curricula, the way it is taught often remains narrow, focusing on macroeconomic data and timelines, rather than exploring the human and social impacts.

Teachers across multiple countries report that crises make a “natural bridge between economics, politics and society,” but lament the lack of structured cross-subject resources available to them to teach the subject in that way.

Comparing today’s cost-of-living squeeze, energy volatility, and uneven recovery to earlier episodes — such as the euro area crisis — helps students draw lessons from history.

Between sluggish growth and tariff shocks, further complicated by an ageing population, Europe is facing a difficult economic road ahead. In such a environment, past crises can provide a framework to make sense of the present ones.