Ageing technology and COVID-19 belt tightening are some of the challenges faced by China in its race to achieve semiconductor independency.

China is currently the world's top semiconductor consumer, accounting for more than 50% of global consumption, according to the Centre for International Governance Innovation. Along with this, it is also the world's fifth largest semiconductor manufacturer, following Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and the US.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

China has also highlighted several times in the past that it aims to become an artificial intelligence superpower in the coming few years. Naturally, the US has not taken kindly to these statements, amid increasing geopolitical and trade tensions between the two countries.

This has led to the US putting several Chinese companies such as Semiconductor Manufacturing International Co (SMIC), China's largest chip market, on a trade blacklist, citing security concerns. This means that major US chip makers, such as Nvidia and AMD now face restrictions on chip sales and exports to China.

The US has justified the move, citing concerns that China may use the advanced chips it gets from Nvidia and similar companies for military purposes, which could be problematic for the US down the line.

According to the **Centre for Strategic and International Studies: "**These actions demonstrate an unprecedented degree of US government intervention to not only preserve chokepoint control, but also begin a new US policy of actively strangling large segments of the Chinese technology industry - strangling with the intent to kill."

China has responded to this with its own graphite export ban on the US. Regarding this, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce said: "The graphite export control policy is a normal adjustment in accordance with the law, and some items are included while some removed from the export control list.

"The export control measures do not target any specific country, region or industry. China is always committed to safeguarding the safety and stability of the global industrial and supply chains, and will grant licences to exports that comply with relevant regulations."

The country has also been trying to ramp up its domestic production of chips as fast as possible. However, this is not without considerable challenges.

What challenges is China facing in semiconductor production?

Much to US dismay, one of the sanctioned companies, Chinese tech giant Huawei, managed to come up with a new smartphone recently, the Mate 60, which uses a 7 nanometer process chip.

This type of chip is considered highly advanced, which has raised increasing concerns about how China is still managing to produce sophisticated chips, despite the sanctions.

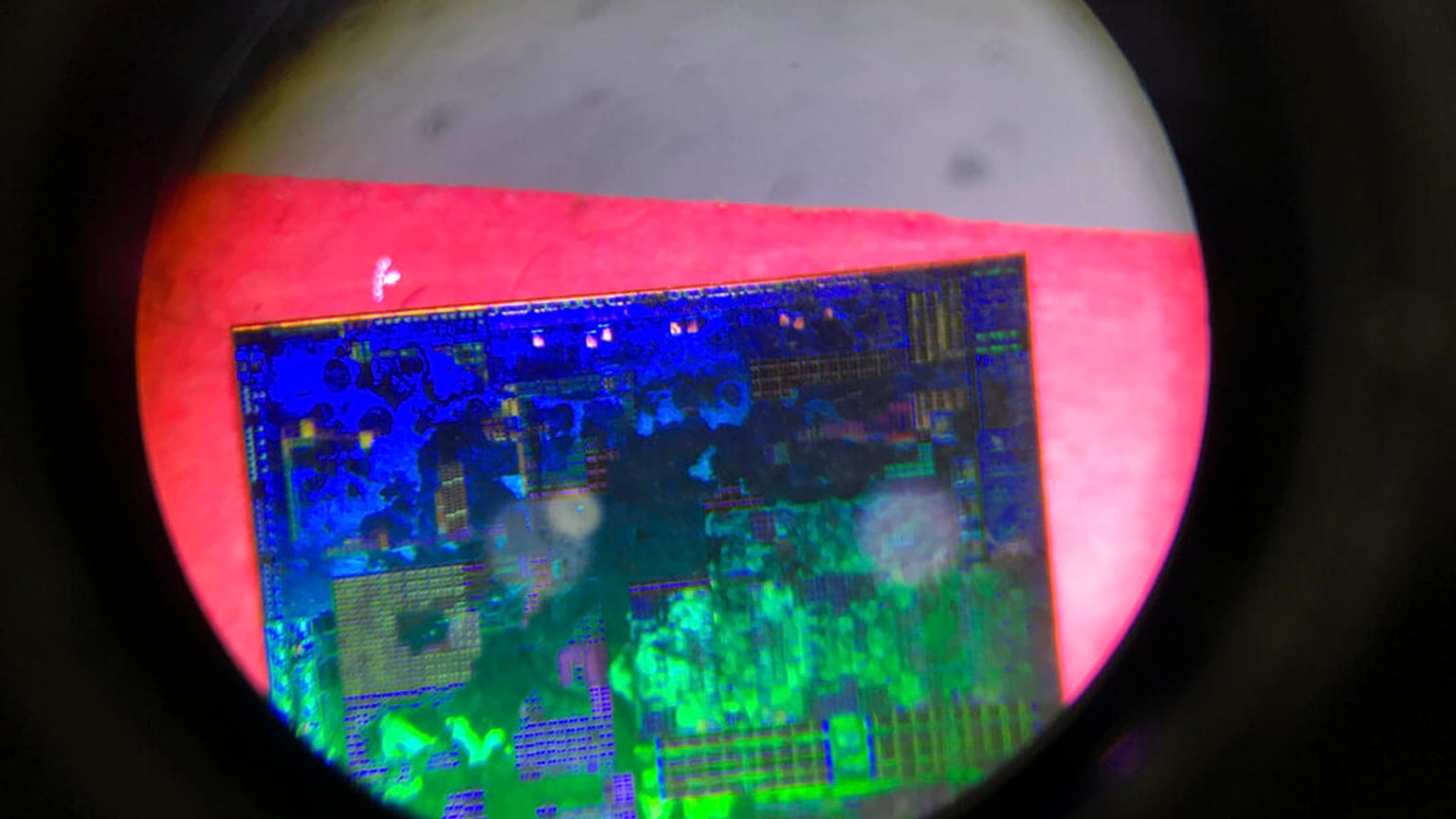

However, one of the biggest challenges that Chinese chipmakers are currently facing is that they are still using old chipmaking technology to produce increasingly complex and new-age chips, as the US has cut off most of China's access to more sophisticated chip making technology.

Using older technology invariably raises costs significantly, meaning that Chinese chipmakers such as SMIC are having to charge about 40% to 50% more than other competitors, especially Taiwanese companies such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. This primary impacts 7 nanometer and 5 nonometer production chips.

The costs are only projected to keep increasing with every new generation of chips. Although this would be significantly helped by an ASML extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography system, the US has also pressurised the Netherlands to restrict China’s access to its chip technology as well.

The other major concern with older chip technology is that the yield is lower, with the number of usable and sellable chips produced being considerably less than with more advanced technology.

Following the pandemic, the Chinese government has also had to put a large chunk of semiconductor funding on hold, as more pressing expenses, such as stimulus measures for various sectors took precedence.

Political and lack of oversight issues, as well as widespread corruption eroding funding for chip research and development programmes have also considerably slowed down the domestic manufacturing process.

Additionally, the country is facing hurdles with intellectual property, with several chip producing technologies already patented and closely protected by international companies.

As foreign affairs and national security website War On The Rocks said: "The Chinese government has allocated the semiconductor industry not only one trillion yuan (€0.13 trillion) through state capital such as the Integrated Circuit Investment Fund (the Big Fund) but also high political priority, directing both political efforts and the market to infuse the chip industry with resources.

"These efforts, however, did not seem to move China up in the semiconductor value chain. Even after billions were thrown at the problem, indigenous production is far from being a reality. Despite some progress in independent chip design for a variety of products ranging from cloud computing to smartphones, the country still could not break free from the foreign-dominated supply and manufacturing chain."

How could China's chip production woes benefit Europe?

Europe has also been an active participant in the semiconductor independence and artificial intelligence dominance race. In 2020, the European Union's share of the worldwide microchips market was about 10%.

The European Chips Act, implemented in 2023, is expected to bring a significant boost to the EU's domestic chip production, taking its global share to about 20% by 2030.

As the European Commission said: "The European Chips Act will bolster Europe's competitiveness and resilience in semiconductor technologies and applications, and help achieve both the digital and green transition. It will do this by strengthening Europe's technological leadership in the field."

Now that China is likely to be considerably delayed in upping its domestic production due to these US sanctions, this gives Europe a rare golden opportunity to ramp up its own production and plug in the gap in the market. As such, it can potentially produce, market and sell its own chips and secure steady clients long before China catches up.

With China already being a rising global superpower with increasing influence in South East Asia and a dominant producer of both rare earth minerals and electric vehicles (EVs), the US and the EU have been feeling more threatened about an economic and trade disbalance in the last few years.

This is because of rising concerns that China may use its dominance over things such as rare earth minerals as a retaliatory or bargaining tool with other nations, effectively cutting them off, if they decide to do so. An example of this was when China stopped exports of rare earth minerals to Japan in a dispute over fishing back in 2010.

Heating EU-China tensions over a number of issues, such as EU investigations over Chinese EV imports to the continent, as well as concerns about data privacy and transparency, have led to increased concerns that China may retaliate against the EU in the near future as well.

If so, it would be far better for the EU to be self-reliant for semiconductors, at least, because of their widespread need and application.