Geopolitical atavism has become fashionable, politically expedient and unchecked by the major powers who are either distracted or complicit. Today the globe is pockmarked with latent or current irredentist disputes, Mark Medish and Alex Rondos write.

History has come roaring back to challenge our sense of global order.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

So long as the post-World War II international system commanded broad respect, we could pretend to keep the peace while camouflaging the contradiction between the principles of sovereignty and self-determination that are embedded in the UN charter.

The system assumed that the world’s dominant powers would contain the contradiction with a combination of appeal to normative rules and a generous application of pragmatism that may have offended many a purist.

The balancing act no longer holds. We are entering a new and very dangerous era made more perilous by nationalist bluster and cavalier ignorance of historical details that should command the attention of major powers.

We need to understand where irredentism comes from

The immediate symptom of the geopolitical malaise is irredentism. The term gets its name from late 19th-century Italian claims on adjacent “unredeemed lands” — Italia irredenta — in the Austro-Hungarian, French and British empires.

We have seen this demon rear its head before, in the 1930s and again with the collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Now the pattern is back with a vengeance. And we must understand it better in its contemporary setting.

It is fundamentally about strife from incomplete decolonisation. The key players are former empires reluctant to admit that they are over and those who believe that the end of imperial control deprived them of a new national redemption.

Decolonisation led to random line-drawing of borders across Africa, the Middle East and other places.

Bureaucrats of the British and French Empires imposed whimsical legacies on the shape of dozens of former colonies. The seeds of irredentism are scattered across the globe. Whether they sprout into new conflicts and how to manage that risk is a central challenge of our time.

Unfinished disputes pockmark the globe

Geopolitical atavism has become fashionable, politically expedient and unchecked by the major powers who are either distracted or complicit. Today the globe is pockmarked with latent or current irredentist disputes.

Russia's aggression against Ukraine, in which Vladimir Putin claims to be reuniting core Russian territories, and the war in Gaza launched by stateless Palestinian groups against Israel are bloody examples of the trend.

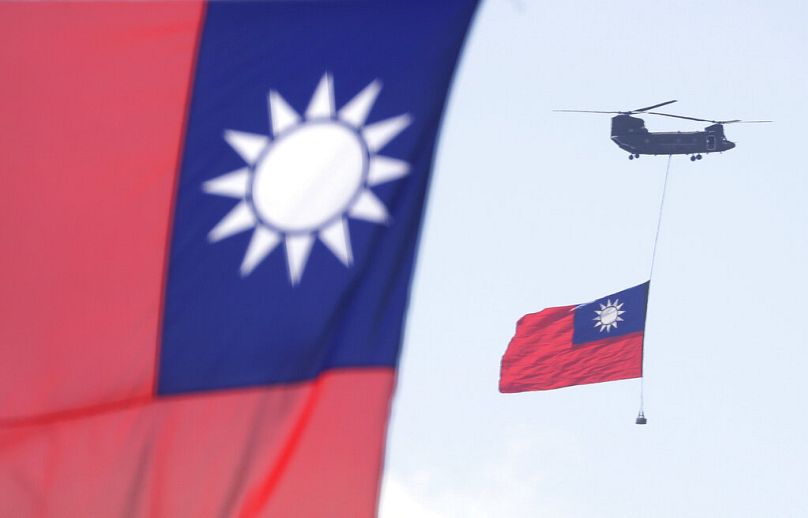

China’s longstanding cross-Strait dispute with Taiwan is a variant of the irredentist theme.

After Azerbaijani forces recently seized the enclave of Nagorno-Karbakh from Armenian settlers, President Ilham Aliyev announced “We have returned our lands, we have restored our territorial integrity […] we have restored our dignity.” This is not aberrant behaviour, but part of a pattern haunting world peace.

A series of "frozen conflicts” from Cyprus to Kashmir to the South China Sea and the Korean Peninsula mark places on the map where contested territorial claims have been long simmering but so far contained largely by diplomatic manoeuvres following military stalemates.

The spirit of the times smells like World War II

Few regions are immune. We are witnessing similar fault lines in the Horn of Africa. Conflict in Sudan and Ethiopia has jeopardised the security of maritime passage in the Red Sea.

Ethiopia has questioned the legality of frontiers drawn over a century ago between the Ethiopian Emperor and the colonial powers of the times and called for permanent access to the sea.

Local regional powers — the so-called “middle powers” — feel they can create spheres of influence either to project control or to protect their security interests. In the case of the Horn, these are principally the powers of the Arabian Peninsula.

The consequences need to be well understood. This is a moment redolent of the runup to World War II. Great powers were consumed by competing ambition and mutual suspicion.

The international order — to the extent the League of Nations represented that — had frayed and the way opened for the reckless and the ruthless to create new realities through violence.

In a world where norms are neither respected nor enforced, the ambitions and fears of countries are reduced to the political manipulation of territory and identity. Multilateralism will be supplanted by regional protection rackets.

Unchecked, these dynamics will generate new types of conflict. Territorial fragmentation, ethnic purification and boundary disputes will proliferate. Local regional powers will seek proxies and local insurgents or weakened governments will seek patrons.

Convening, not coercing — this is the way

How to put the genie back in the bottle? In the absence of a world government with enforcement tools, the dream of a liberal world order without hot territorial disputes is a chimaera.

However, mutual interest in the avoidance of chaos argues for pragmatic management. Frozen conflicts are better than hot ones.

Military force cannot provide durable solutions but instead usually lays the ground for a harvest of new grievances. Diplomacy is key. If irredentist conflicts continue to erupt, it should not be for lack of diplomatic efforts by stakeholders and honest brokers.

Back-channel talks and negotiations between belligerents are not a sign of weakness. Pragmatism calls for countries within regions in dispute to get more used to talking to each other directly.

If they don’t, they will be consumed by the interference of their richer and more powerful neighbours or by far more radical or criminal movements that don’t care either for boundaries or states.

To prevent protection rackets from prevailing, it also falls to great powers like the United States, the European Union, the UK, and others of like mind who do not wish for chaos, to use their formidable diplomatic capacity to convene — not coerce — parties towards new regional regimes of territorial integrity and non-interference.

The alternative to pragmatism is the abyss. As UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold once said, the point is “not to take mankind into paradise, but to save humanity from hell.”

Mark Medish is a former senior White House and US Treasury official in the Clinton administration who now serves as vice chair of PA Group, a strategic consultancy. Alex Rondos is former EU special representative for the Horn of Africa and serves as a senior adviser at the US Institute of Peace (USIP).

At Euronews, we believe all views matter. Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.