The country's second-most populous state has a long tradition of mainstream conservative politics, but trends towards the extreme are detectable.

With recent polling showing that support for far-right extremism is on the up in Germany across all age groups, this weekend's election in Bavaria could shed some light on what is happening in the German electorate outside the areas most commonly associated with the radical right.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Unlike regions such as Saxony, where the hardline Alternativ für Deutschland, or AfD, has made its biggest gains, Bavaria's politics have remained more mainstream in recent years.

The state is currently headed up by a coalition of the Christian Social Union, or CSU, traditionally the state’s largest party, and a smaller party known as the Free Voters of Bavaria, or FW. (The Greens came second at the last election in 2018, and the AfD fourth.)

While the CSU is a long-established centre-right party with a relatively traditional stance on social issues, the FW is a looser entity pulling together former independents who between them hold a wide range of views. And among their most senior figures are people whom many German voters might consider beyond the pale.

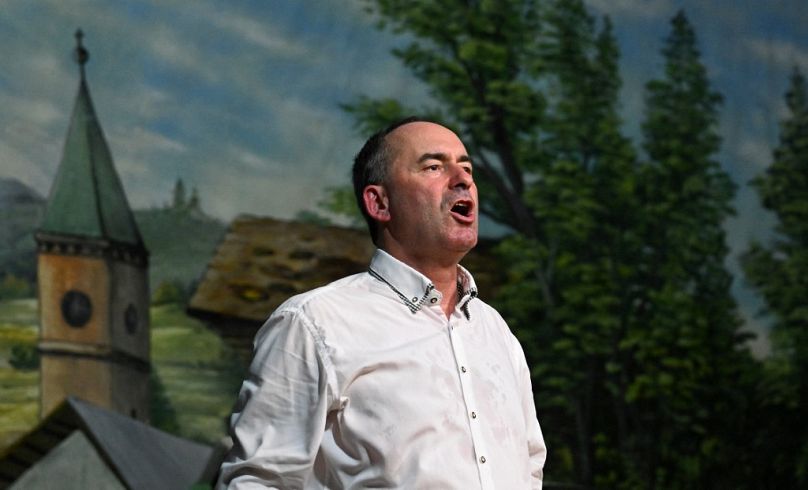

One of them is Hubert Aiwanger, who sits as Bavaria’s current deputy minister. Earlier in the year, he was accused of having written an explicitly antisemitic pamphlet while a schoolboy in the 1980s. The document in question made light of the Holocaust, proposing a competition for “the biggest traitor to the Fatherland” and promising the winner “a free flight through the chimney in Auschwitz”.

When the leaflet’s history was first reported by the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper this summer, Aiwanger denied having written the document (which his brother Helmut admitted putting together) and decried the story as a campaign against him, but did admit carrying copies around at school.

Bavarian premier and CSU leader Markus Söder asked Aiwanger to answer 25 questions; the answers were clearly satisfactory for Aiwanger to keep his post, though Söder maintained his disgust at the pamphlet's "Nazi jargon".

The Aiwanger leaflet affair is not just a mortifying scandal for a politician not keen to be associated with Nazism. It is also a reminder that for all the national and international focus on the extremism of the AfD, fears of a far-right resurgence in German party politics are not confined to one party or to the left-behind regions of the former East Germany.

Franziska Schröter, a political and social researcher at the Friedrich Ebert Institute, told Euronews there is plenty of evidence that the regionalisation of the far right vote has been overstated.

“Numbers in the East are higher, especially also for hardline far right extremist views,” she said of recent surveys. “But numbers are rising in the west as well – and in the Bavaria election, we expect higher AfD numbers despite a very conservative CSU and a super right-wing populist FW probably coming in first and second.

“The numbers in the East can be explained culturally,” she said, “but it also has a demographic component to it: more men, more older people, more rural area, structurally challenged, more workers, well-educated people moving away. This is all a big part of the explanation.”

All the while, the parties that make up the "traffic light" coalition running the federal government are currently polling behind the AfD. If the combined AfD and FW vote in Bavaria sees a surge even after Aiwanger's leaflet scandal, it could be a new wake-up call for anyone who assumes that the far-right's successes can be pinned on poorer East German regions feeling "left behind" since the 1990s.

As Schröchter pointed out, while the AfD's gains in the East and indications of extremism gaining ground there are both very real, it's important not to miss the national picture.

“The far right in the east consists in large part of West German cadres," she explained. "The structures there are full of Neo-Nazis from Dortmund and other places moving east because they see an opportunity.”