Supporters of the reform, due to be approved by lawmakers on Thursday, argue that Greek universities have long been plagued by violence and those against it are afraid it will hinder freedom of expression.

Greek students have been demonstrating around the country against a law that would establish a university police force, which they say will stifle freedom of expression.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The legislation, proposed by the ruling centre-right New Democracy party and due to be approved by parliament on Thursday, aims to reform the education system. It plans for the creation of a special university police force empowered to guard campuses and arrest those considered troublemakers as well as a "disciplinary council" able to suspend or expel students.

Supporters of the reform argue that Greek universities have long been plagued by violence and those against it are afraid it will hinder freedom of expression.

"The problem of violence in Greek universities is timeless. The police will drive out extremist political groups and guard the infrastructure, finally making the university a safe place" a spokesperson for the Ministry for Citizen Protection told Euronews.

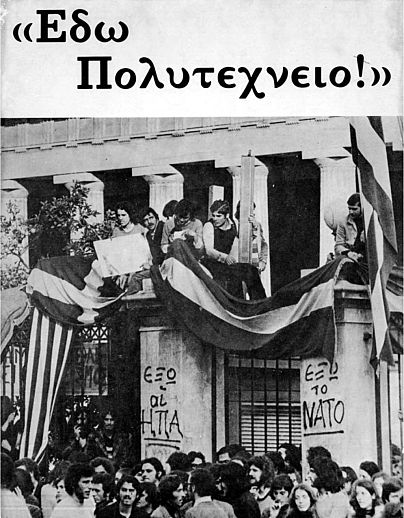

Many dark moments in Greece's recent history have taken place in universities and schools. In 1973, tanks of the Greek junta or 'Regime of the Colonels' — which fell a year later — violently ended a student occupation of Athens Polytechnic. At least 26 people were killed.

The 1990/91 protest against a reform of the high school system wanted by the government of Konstantinos Mitsotakis — the father of current Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis — also led to the death of one teacher.

Last October, the rector of the Athens University of Economics and Business was taken hostage in his office by a group of hooded anarchists, who photographed him with a sign around his neck saying, "Solidarity with squats".

'Bread, education and freedom'

A "university asylum law" which prevented police from entering campuses except for particularly serious crimes was ushered in after the military dictatorship. It was repealed by New Democracy a year and a half ago.

The latest reform makes some who remember the students' uprising in the 1970s uneasy.

"The idea of a university police brings me back to a very painful time," Nikos Manios, a former student who opposed the dictatorship, told Euronews.

"At end of the military junta, I came back to the university to enrol again, as I had been expelled during the resistance. On campus, I met the person who had tortured me during my imprisonment. He kept spying and taking notes of students enrolling at the university as he had done in the past."

"There I realised that the dictatorship might have ended, but the universities were still in danger of being controlled by political power," he added.

During the student demonstrations that have been going through the centre of Athens every week for the last month, protesters have been chanting "Bread, education and freedom" — a traditional slogan of the students who opposed the dictatorship.

The government refutes that the reform will stifle freedom. "It is ridiculous to think that the police will spy on the students," the spokesperson for the Ministry for Citizen Protection said.

"On the contrary, it will help the rectors to ensure the free flow of ideas that are threatened right now by some extremist groups," they went on.

But for Maria Kalkoni, a student protester, the argument doesn't hold up.

"It happens that groups of self-styled anarchists occupy university classrooms or damage equipment. However, these episodes do not hinder university activities as the government would have us believe," she told Euronews.

'Chronic underfunding'

Thousands of Greek professors have also urged the government to withdraw the bill.

"The problem of the Greek universities is not about police but the lack of funding," Dimitris Kaltsonis, Professor of State Theory and Law at Panteion University, told Euronews.

"According to surveys, the crime rate in Greek universities is in line with that of other countries. Moreover, the police can already enter universities if a crime is committed: there is no need for special police to control the campuses," he argued.

New Democracy has refuted that the reform will curb freedom of expression and says it establishes control measures already in place in most European universities.

The Oxford Local Association of the University and College Union (UCU) have expressed solidarity with Greek professors opposing the reform, writing in a press release that it "is unlikely to respond to the most pertinent problems of Greek higher education institutions, such as chronic underfunding."

"The University of Oxford does not have a university police force, security on University premises is provided by the University's own personnel," it also said.

The Minister for Citizen Protection Michalis Chrisochidis recently told parliament that the reform opens the door to rectors being able to eventually hire private guards. But, he stressed, "this solution is not feasible at the moment, but only when the police eradicate criminal groups from universities."

'More doctors, fewer police'

The role of the police is also increasingly in the spotlight with students calling in recent demonstrations for "more doctors, fewer police" and "funds for education ad health system, not state repression."

"Since Kyriakos Mitsotakis was elected in 2019, he has kept hiring new policemen in response to every alleged problem. This policy has brought nothing but more riots and a climate of fear," Alekos Akridas, a student protester, told Euronews.

The government recently unveiled a €23 million budget for the police to "face contemporary challenges, such as COVID-19 and external threats". The Transport Minister has also said he is keen to create a police force to ensure safety on public transport.

Yet, according to Eurostat figures from 2016-2018, Greece has the second-highest number of police officers per inhabitants in the European Union after Cyprus.

Human rights observers, such as Amnesty International, have highlighted an increase in police abuses in Greece in the last year and a half, often favoured by the lockdown, which is still in force.

For the spokesperson for the Ministry for Citizen Protection, "Eurostat data are inaccurate because each country defines its police force differently."

"In Greece, many law enforcement agencies are united in a single body, contrary to what happens in other countries. That is why it seems that Greece has so many policemen, but in reality, it does not.

“Nonetheless, we are investing in the quality of education as well, because universities are not safe places at the moment. Police on campuses is not a choice, but a necessary move," he concluded.