The Czech Republic is on a par with France when it comes to scepticism or hesitancy over taking vaccines.

For the vast majority of Europe, the first groups to be given a COVID-19 vaccine have been the most vulnerable: the elderly or healthcare workers.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

But, in the Czech Republic, they have done things differently.

In an apparent nod to the country's overall confidence in vaccines, the first person to get the jab was Prime Minister Andrej Babis.

It was part of the government’s new publicity campaign to tackle widespread vaccine scepticism, which appears so entrenched that senior politicians are worried that it may not be possible to get two-thirds of the population immunised.

Experts say between 60 and 70% of the population need to have had the COVID-19 vaccine for the disease to be eradicated.

What are the levels of vaccine scepticism in the Czech Republic?

A survey by STEM, a local pollster, in early December, found that only 40% of Czechs would willingly be vaccinated, amongst the lowest rates in Europe.

A regional poll conducted by Sinophone Borderlands project of Palacky University Olomouc painted a more worrying picture: only 30% of Czechs would be willing to vaccinate against COVID-19, the second-lowest score of the 13 European countries surveyed and just behind Slovakia. It compares with 31% of French, 52% of Germans and 62% of Britons.

Why are Czechs sceptical of vaccines?

Richard Q. Turcsanyi, of Palacky University and lead researcher of the survey, says there is greater scepticism in Eastern Europe than Western states over the vaccine.

He puts the Czech situation down to a mixture of lack of trust in the government, widespread disinformation, propaganda from Russia, and misunderstanding of science.

After Babis’ inoculation, conspiracy theories were quick to spread on social media. Some claimed that video footage didn’t show the needle going into the prime minister's arm, as the doctor’s hand masks this, and was a scam. Others claim he was injected with a placebo.

The main reason to be sceptical of the COVID-19 vaccines is because they have been “hastily developed [and] have not been properly tested for safety and efficacy”, whilst the public is not properly informed about the possible side effects of this vaccine,” according to David Formanek, creator of the website Open Your Mind (Otevři svou mysl), whose Facebook page is followed by 20,000 people.

For months, it has decried the government‘s pandemic measures as a new form of authoritarian control - in a country where 12,436 have died of COVID-19, as of January 6 - and spread other conspiracy theories.

It has recently created a new, professional-looking site, Risks of Vaccines, which includes translated videos of talks by claimed doctors and medical experts, including one with the controversial British author Vernon Coleman.

Now, Formanek claims the Czech government will set conditionality on the vaccine, with those vaccinated allowed to travel as normal but those who refuse still facing stiff restrictions.

“It is basically a ‘compulsory vaccination’ in another package,” he added. “I firmly hope that people will strongly demand that this vaccine not be conditional… and instead be truly voluntary.”

'Czechs have a media literacy problem'

Jan Cemper, editor-in-chief of the anti-misinformation website Manipulátoři.cz, which has often rebutted suggestions made on Formanek’s sites, says that many websites and online groups have sprung up in recent months to spread misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines.

But, in response, new anti-misinformation news sites have also been created, including the recent addition of infomore.cz, created by science faculties of Charles University and Masaryk University in Brno, as well as a media organisation.

“In the Czech Republic, there is generally a problem with media literacy. People don't really check what is written on the internet,” Cemper said, adding there has been a lot of false information about vaccinations for years, not just with COVID-19.

In 2018, then-Vice Minister of Health Roman Prymula said misinformation about vaccines was the reason for a measles outbreak in Prague.

“We have whole communities of people who are exposed to constantly repeated untruths about vaccination and they start to believe them,” he commented in 2019 amid another debate in local media about the rise of anti-vaxxer sentiment.

A report published in late 2018, The State of Vaccine Confidence in the EU, funded by the European Commission, found that 36% of surveyed GPs in the Czech Republic thought the MMR vaccine to be unsafe, one of the highest rates in Europe and the only country where medical professionals were more sceptical of it than the general public.

One frequently made claim is that Czechs are inherently more suspicious of official narratives and expert opinion because of the country’s communist past when scepticism of the Communist Party’s version of the truth was often justified. But this wouldn’t explain why the study from 2018 and surveys from this year find that anti-vaxxer sentiment is more common amongst those aged between 25-34, the majority born after the fall of communism in 1989, than over 65s.

Another view contends that the Czechs are by nature sceptical and mistrusting. A Pew Research survey from 2018 found they are the third-least religious in Europe, with only 8% of respondents claiming to be “deeply religious”, compared to 29% in neighbouring Slovakia.

But the Sinophone survey also found that only a third of Czechs believed the conspiracy theory that COVID-19 was artificially made in a Chinese lab, compared to half of Polish respondents and 41% of Spaniards.

Does government distrust play a role in vaccine scepticism?

Historical and cultural reasons no doubt are part of the explanation for why Czechs are deeply suspicious of COVID-19 vaccinations. So do more universal concerns over the speed at which the vaccine was produced and the approved. But distrust of this particular government is another factor.

Babis, a billionaire populist, was elected prime minister in 2017 whilst the EU was investigating him for subsidy fraud, a case that is ongoing. In fact, he campaigned on an anti-corruption ticket.

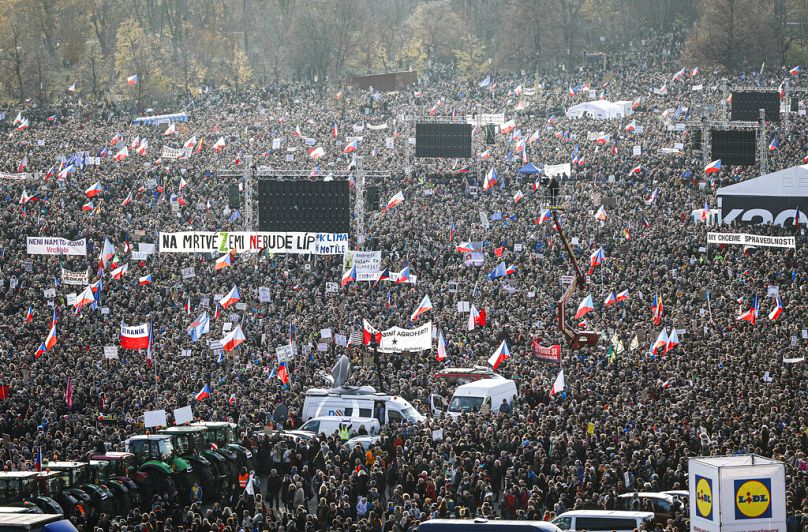

The largest protests seen since the Velvet Revolution of 1989, which brought down communism, took place last year against Babis’ government and President Milos Zeman, who critics say wants to rule autocratically.

This distrust hasn’t been helped by the government’s handling of the pandemic, which was often chaotic at the beginning even though the country did relatively well in the first few months.

With the country expected to receive at least 355,000 doses between now and the end of January, as part of its total order of 15.9 million shots, the question for the government now is how to enforce the vaccination of 70% of the population, its stated aim, when the majority of the public is opposed to it.

“The real problem is that a large part of the population may resist getting vaccinated,” Dr Miloslav Janulík, deputy chairman of the Chamber of Deputies’ health committee, commented in local media in November.

Lessons from the lockdown would suggest the authorities will struggle to instigate a widespread vaccination programme by force - and if the government was to try to enforce it through strong-arm measures, this might only increase opposition to the vaccine.

After responding well during the first months of the pandemic, by July the government had lifted almost all restrictions, one main reason why the Czech Republic had the highest infection rate per population in Europe in October, amid the second-wave of the virus. Since then the authorities have struggled to maintain public compliance with much stricter rules, and Prime Minister Babis has lashed out on several occasions at the public.

The government has also been slow to counter the spread of anti-vaxxer messages. Dr Vlastimil Valek, vice chairman of the opposition party TOP 09, castigated it in November for not having already instigated a publicity campaign and blamed the new Health Ministry, Jan Blatny, for allegedly shelving a campaign when he took charge the previous month.

The government appears to have begun remedying this, with Babis very publicly receiving the country’s first shot, produced by Pfizer-BioNTech, before the country's other 9,750 doses were distributed.

According to Cemper, many Czechs are playing the waiting game and will make their decision on whether to vaccinate themselves depending on how well the first roll-out of inoculations goes.

“The fact that the vaccine is untested is one of the common narratives. Another is the side effects,” he said.

“The problem is also that it is not yet known what benefits vaccinated people will have.”

It is also possible that the surveys are misleading. Respondents may find it relatively easy to tell a pollster that they wouldn’t receive a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine, but once they are freely available and could potentially save lives it’s a rather different matter.

Every weekday at 1900 CET, Uncovering Europe brings you a European story that goes beyond the headlines. Download the Euronews app to get an alert for this and other breaking news. It's available on Apple and Android devices.