As the world scrambles to find a COVID-19 vaccine, this is a rare bit of good news.

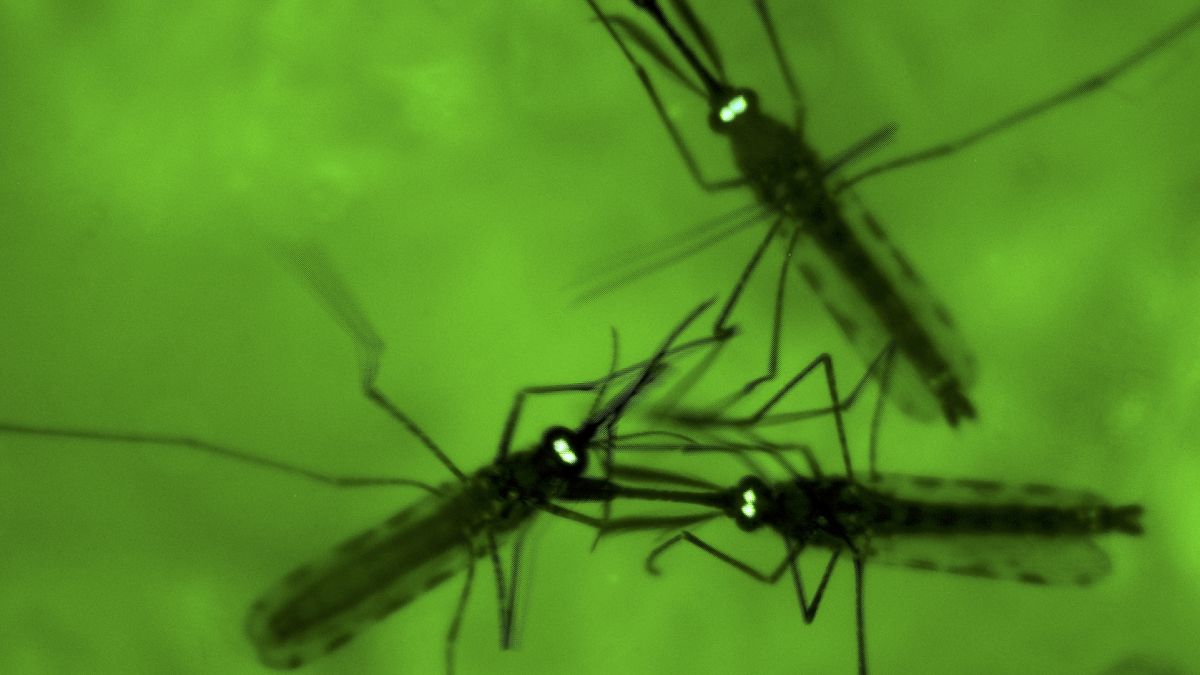

Scientists have discovered a microbe they say can prevent mosquitoes from transmitting malaria.

Jeremy Herren, a researcher at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, told Euronews it was a critical first step towards "a new way of controlling malaria".

Infected mosquitoes spread malaria to humans so any control over the number of the insects with the disease can help save lives.

The World Health Organization estimates malaria killed 405,000 people worldwide in 2018, more than 90 per cent of which were in Africa.

The group of scientists, from the UK and Kenya, published their discovery in the scientific journal Nature.

What is this microbe?

It's a distant relative of fungi, or microsporidian, that inhabits another organism, Herren explained.

"Many of these cause illness in insects but this one has opted to not cause overt harm to its mosquito host: it is a 'symbiont'".

"When a parasite like this one is steadily associated with their hosts, they tend to improve their own survival by helping their hosts to survive.

This particular microbe "is transmitted across mosquito generations, which likely explains why it has opted to ‘help’ rather than ‘harm’ its mosquito host," Herren added.

How important is this discovery?

Herren said the study has shown the microbe can make mosquitoes "malaria resistant" and that it is very efficient in blocking the transmission of the infection.

"Step two is increasing the levels of the microbe in mosquitoes, which will be the hard part, but it is very encouraging to see how infectious this microbe is," he added. "Its ability to be spread from a mother mosquito to her offspring is an incredibly powerful feature."

Herren said the scientists are studying other ways the microbe could spread through the mosquito population, such as releasing spores.

Dr Segenet Kelemu, director-general of the ICIPE, said: “Given recent developments in Africa and globally, the importance of scientific advancement has never been more real. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the current locust outbreak in eastern Africa, and the fall armyworm invasion that has been ongoing since 2016 place a most urgent call-to-action for science and scientists, policymakers and development partners.”

When and how can it be applied to stop the spread of malaria?

"Using a living organism as a prevention or treatment isn’t new, but it requires many questions to be answered first," said Morgan Gaïa, a postdoctoral researcher at CEA - Genoscope.

"Is there another potential host for the parasite that could spread it out of control? What is the mechanism of malaria control through this parasite infection, and would it be possible or safer to mimic it instead of using the entire parasite? How to disseminate the parasites? Does the infection with this parasite have other effects that could be negative? Are all malaria-carrying mosquitos sensitive to this parasite, and will the infection maintain over time?

"They might already have some answers, but it is not a trivial decision, and it will likely take some time," he added. "Nonetheless, this sounds like a very promising lead."

The group of scientists is currently studying the epidemiology of the microbe in captive mosquito populations.

This is a second phase of research will last until the end of 2021.

"This will allow us to understand the routes and rates of spread, at which point we could design a strategy for deployment," Herren said.

"What is very encouraging is that it is a natural microbe that is already present in some populations of mosquitoes in Africa and therefore there is a much lower risk associated with its dissemination, compared to introducing a foreign agent.

"I think that in light of this, if it spreads well, we could have something useful in a relatively short time frame," the researcher concluded.

A critical discovery for Africa

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that there were 228 million malaria cases worldwide and 405,000 deaths.

To put this in context, since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak more than five months ago, it is estimated that there have been more than 3 million cases worldwide and 250,000 deaths.

But the incidence of malaria is disproportionate. In 2018, Africa was home to 93% of malaria cases and 94% of malaria deaths.

"The malaria burden remains a major impediment to economic development over many regions of sub-Saharan Africa," the study noted.

"Large-scale insecticide-treated net (ITN) distribution campaigns over the previous 15 years have reduced malaria cases by an estimated 40%. However, progress has plateaued; between 2014 and 2016 global incidence remained essentially the same."