UNHCR in Libya Part 4: The detention centres - the map and the stories

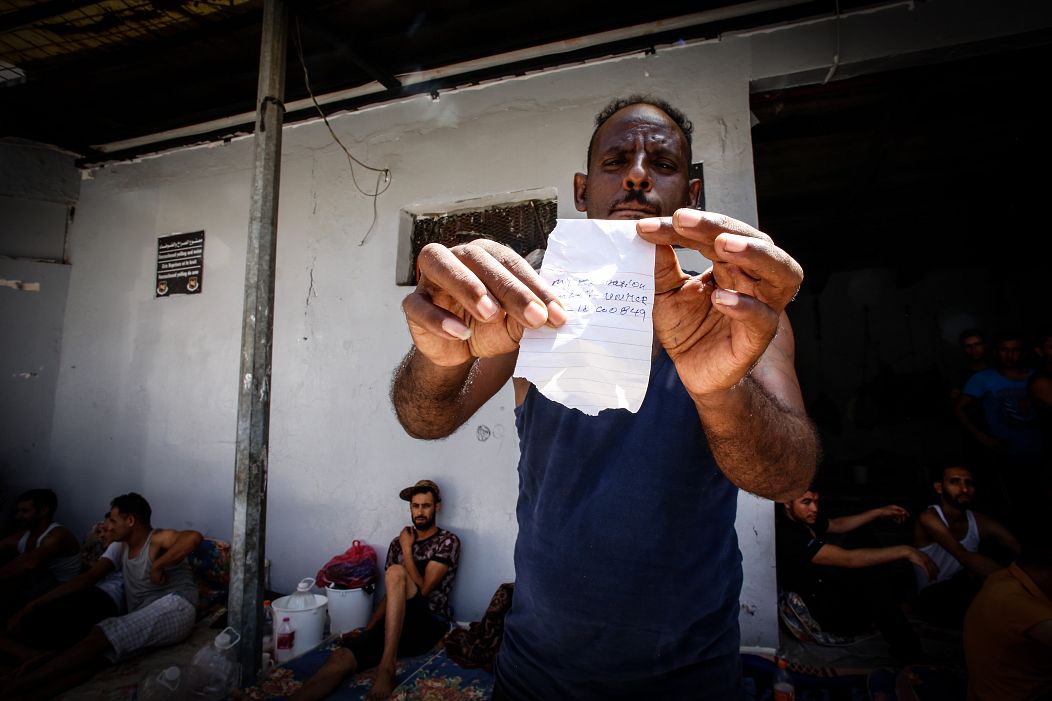

In February 2019, the Libyan government revealed that there were 23 detention centres operating in Libya, holding over 5,000 asylum seekers. While they are officially run by the government, in reality it is Libya’s complex patchwork of militias that are in control.

When NGO workers arrived at the Janzoor detention centre in Libya in October 2018 to collect 11 unaccompanied minors due to be returned to their country of origin, they were shocked to find that the young people had completely disappeared.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The failed asylum seekers were registered and ready to go, a staff member at the International Organisation of Migration, who wished to remain anonymous, told Euronews. It took six months to find out what had happened to the group.

“They were sold and their families were asked for ransom”, the former staff member said.

In February 2019, the Libyan government revealed that there were 23 detention centres operating in Libya, holding over 5,000 asylum seekers. While they are officially run by the government, in reality it is Libya’s complex patchwork of militias that are in control.

Even those ostensibly run by Libya’s Directorate for Combatting Illegal Migration (DCIM) are effectively under the control of whichever armed group controls the neighbourhood where a centre is located.

Rule of militias

Militias, also known as “katibas”, are de-facto in control of the gates of the centres and the management. In many cases, migrants and refugees are under arrest in locations which are not considered official detention facilities, but “holding places” for investigation.

By correct protocol, they should be sent to proper detention facilities, but in reality procedures are seldom respected and asylum seekers are detained with no legal review or rights.

For many migrants and refugees, the ordeal begins at sea.

According to the Libyan coast guard, from January to August 2019, nearly 6,000 people were intercepted and brought back to Libya.

On September 19, a man from Sudan died after being shot in the stomach hours after being returned to shore.

The IOM, whose staff witnessed the attack, said it occurred at Abusitta disembarkation point in Tripoli, when 103 people that had been returned to shore were resisting being sent back to detention centres.

IOM staff who were on the scene, reported that armed men began shooting in the air when several migrants tried to run away from their guards.

“The death is a stark reminder of the grim conditions faced by migrants picked up by the Coast Guard after paying smugglers to take them to Europe, only to find themselves put into detention centres” said IOM Spokesperson Leonard Doyle.

With conflict escalating in Tripoli and many detention centres located on the frontline, the majority of the people intercepted by Libyan coast guards are brought to al-Khoms, a coastal city 120km east of the Libyan capital.

Tortured, sold, and released

According to UN sources, guards at the city’s two detention facilities - al-Khoms and Souq al-Khamis - have either facilitated access to the militias or were afraid to deny them access.

“Let me be honest with you, I don’t trust anyone in al-Khoms centre,” a former DCIM official told Euronews.

“The detention centre has been officially closed by the DCIM but the militia there do whatever they want and they don’t respect the orders given by the Ministry of Interior.

“People have been tortured, sold and released after paying money. The management and the militia in al-Khoms, they act independently from the government”.

Last June, during the protection sector coordination meeting in Tripoli, UN agencies and international organisations raised the question of people disappearing on a daily basis.

“In one week at least 100 detainees disappeared and despite the closure of the centre, the Libyan coast guard continued to bring refugees to al-Khoms detention centre” according to a note of the meeting seen by Euronews.

The head of an international organisation present at the meeting, who asked to remain anonymous, said: “Many organisations have been turning their back on the situation, as they were not visiting the centre anymore.

“19 people from Eritrea were at risk, including young ladies between 14 and 19 years old”.

During a press briefing last June, the spokesman for UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Rupert Colville, reported that women held in detention have been sold into sexual exploitation.

David, a migrant who had been detained in Misrata detention centre was able to get out after transiting from a safe house in al-Khoms. He said that centre staff “had been extorting money from detainees for months.

“I didn't have a choice as the UN refused to register me because I come from Central African Republic and my nationality is not among the one recognised by UNHCR.”

Detention centres are still open

In August 2019, Libyan authorities in Tripoli confirmed the shutdown of three detention centres in Misrata, Khoms and Tajoura, but DCIM officers and migrants held in detention confirmed to Euronews that the centres are still open.

While it is impossible to independently verify the current status of the facilities - as as the Ministry of Interior in Tripoli does not authorise access to them - Euronews was able to speak on the phone with detainees.

“Just bring a letter with the authorisation from the Ministry of Interior and I will let you enter,” said one commander from Tajoura on the phone, confirming that the centre was still running.

Another source at the DCIM in Tripoli mentioned that Tajoura was still running and the militia was mainly arresting people from street to fill the hangars again.

The decision to close the Az-Zāwiyah detention centre - mentioned in PART 1 and 2 - was taken in April 2018 by former head of DCIM Colonel Mohamed Besher. But the centre has instead been transformed into an arrest and investigation centre.

Located at the Az-Zāwiyah Refinery, which is secured by Al-Nasser brigade since 2011, it is close to the base of the Az-Zāwiyah coastguard

Both the commander of the Libyan Coast Guard’s Unit and the head of Al-Nasr brigade are sanctioned by UN and the United States for alleged involvement in human trafficking and migrant smuggling.

Mohammed Kushlaf is working in cooperation with “Osama” (➡️ SEE PART 2), who is in charge of the detention facility. His name appears 67 times in the recent investigation conducted by Italian prosecutor Luigi Patronaggio.

‘Inhumane conditions’

The investigation had “confirmed the inhumane conditions” endured by many migrants and “the need to act, at an international level, to protect their most basic human rights.”

The Government of National Accord has supported the UN sanctions and issued public statements of condemnation against the trafficking and smuggling of migrants.

The Libyan prosecutor has also issued an order to suspend the commander of the Libyan Coast Guard and bring him into custody for investigations, although this was never implemented, confirmed a Libyan lawyer working at the Ministry of Justice.

Sources at the DCIM mentioned that between September 2018 and April 2019 - when the Libyan National Army (LNA) troops guided by the general Khalifa Haftar seized Tripoli's southern suburbs – many detention centres were located near the clashes.

Salaheddin, Ain Zara, Qasr Bin Ghashir and Tariq Al Matar detention centres have been closed because of the conflict.

As a result, large groups of refugees and migrants have been displaced or transferred to other locations. A DCIM officer in Tripoli mentioned that “The Tariq Al Matar centre was in the middle of the clashes and many refugees left to find safety in other areas after a few people were injured. A group was transferred to Ain Zara and another to Janzour detention centre, some 20 kilometres southwest of Tripoli's centre.”

Migrants being recruited to help militia in Libya's civil war

In September and several times in December and January, refugees say they were forced to move and pack weapons as fighting between rival armed groups in the capital of Tripoli flared up.

They also engaged directly with local militia, from the Tripoli suburb of Tarhouna, that was controlling Qasr Bin Ghashir detention centre at the time.

“No one was fighting on the front but they would ask us to open and close the gate and move and pack weapons”, said Musa, a Sudanese refugee who left Qasr Bin Ghashir in April following the attack.

On October 2, Abdalmajed Adam, a refugee from South Sudan was also injured by a random bullet on his shoulder and was taken to a military hospital,” adds Musa.

The militia who is controlling the area where Abu Salim detention centre is located is known as Ghaniwa and is aligned to the GNA.

The group has been asking refugees, especially Sudanese – as they speak Arabic - to follow them to the frontline.

“Last August they bought us to Wadi Al-Rabea in southern Tripoli, and asked us to load weapons. I was one of them. They took five of us from the centre,” said Amir, a Sudanese asylum seeker who is detained in Abu Salim.

A former DCIM officer confirmed that in June 2018, the head of Abu Salim DCIM, Mohamed al-Mashay (aka Abu Azza), was killed by an armed group following internal disputes over power.

The Qasr Bin Ghashir detention centre, in which 700 people were locked up, was attacked on April 23. Video and photographic evidence shows refugees and migrants trapped in detention having incurred gunshot wounds.

Multiple reports suggested several deaths and at least 12 people injured. A former DCIM officer mentioned that behind the attack there was a dispute over the control of the territory: it is a very strategic point being the main road to enter to Tripoli.