Among black leaders, support for a black candidacy was far from universal.

Many black leaders, including some icons of the civil rights movement, plead with Jesse Jackson not to run for president, convinced his campaign will harm their cause. But he defies them and then defies all expectations in a campaign that radically expands the role of black voters in national Democratic politics.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The frustration of 1980 created urgency among black leaders not to be marginalized again.

Among some, an idea took shape: recruit a black presidential candidate. It picked up momentum early in 1983, when Rep. Harold Washington of Illinois triumphed in Chicago's Democratic mayoral primary, an upset that positioned him to become the first black mayor of America's second-largest city.

Proponents envisioned a black presidential candidacy accelerating the registration of new black voters, forcing the political and media establishments to address issues they might otherwise ignore, and possibly even leveraging a strong showing into the vice presidential slot. Meetings were held, studies commissioned and names bandied about as possible candidates, including Walter Fauntroy, who had organized a slate in D.C.'s 1976 primary and still represented the district in Congress, and Tom Bradley, the mayor of Los Angeles, among others.

With black leaders, however, support for a black candidacy was far from universal.

#embed-20190604-black-votes-nav iframe {width: 1px;min-width: 100%}

Andrew Young, who'd become mayor of Atlanta after his Carter administration tenure, argued that it would be wiser for the black establishment to spread out its support so that it would be represented in every major presidential campaign and be guaranteed some leverage with the ultimate winner — an approach that the Rev. Joseph Lowery of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference argued against. "Andy was on the inside with Carter, but what did that get? All it got him was to the U.N., and it got him fired," Lowery said. ("Black Leaders Hear Plan for Key Role in Democratic Convention," Milton Coleman, The Washington Post, March 13, 1983.)

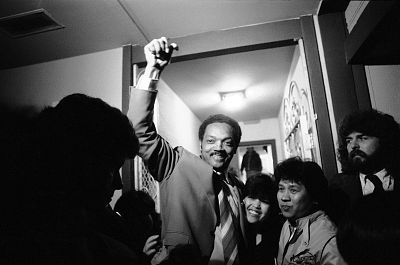

While the debate continued, a candidate volunteered: the Rev. Jesse Jackson, still the Chicago-based leader of Operation PUSH. Aggressive in his pursuit of media coverage, Jackson was by now well known nationally, and a poll showed him running at 9 percent in the Democratic race — far behind the front-runners Walter Mondale and John Glenn, but better than any other aspirant.

In early November, Jackson announced his candidacy. "We are members of the party and we don't want to leave," he said, "but our self-respect is nonnegotiable." ("Jackson Declares Formal Candidacy," Ronald Smothers, The New York Times, Nov. 4, 1983.)

Even Jackson's supporters generally conceded that he had no realistic path to winning the nomination, and his candidacy was not widely welcomed by leaders of the black political establishment.

"Since we are so frightened by the Reagan system of government," Benjamin Hooks, then executive director of the NAACP, said, "our primary concern should be ridding the nation of that system. Therefore we should vote for that candidate most likely to achieve that end." ("N.A.A.C.P. Chief Warns Against Black Candidacy," The New York Times, July 4, 1983.)

Among civil rights veterans, Jackson remained a polarizing figure. Young refused to endorse him, and so did Coretta Scott King and Julian Bond. Many black leaders instead sided with Mondale. Jackson shrugged it off: "Gandhi didn't go to the leaders for approval for his movement. Neither did Jesus." ("Jesse Jackson: His Charismatic Crusade for the Voters at the End of the Rainbow Coalition," Lois Romano, The Washington Post, July 31, 1983.)

Not surprisingly, Jackson finished in single digits in the lead-off contests in heavily white Iowa and New Hampshire. His big test came on Super Tuesday, with primaries in three Southern states with significant black populations: Alabama, Florida and Georgia.

#embed-20190521-dem-pres-primary-results-by-year iframe {width: 1px;min-width: 100%}

Jackson's viability was on the line: He needed to break 20 percent in at least one state or he'd be shut out of federal matching funds — and dismissed by the media. The trio of primaries was equally critical for Mondale, who was banking on strong African American support and whose candidacy was suddenly on the verge of collapse after a stunning blowout loss to Gary Hart in New Hampshire.

They both got what they needed. Mondale pulled in about a third of the black vote, enough to propel him past Hart in two of the contests, Alabama and Georgia, and put his candidacy back on track. But when it came to black voters, Jackson was the big winner, claiming an outright majority of black support in the three states, according to NBC News' black voter data analysis.

"I feel like if we don't pull the lever for Jackson, Martin Luther King might turn over in his grave, and we want him to rest in peace," one voter in rural Alabama was quoted as saying. ("Reckoning Day For Jesse Jackson," Art Harris, The Washington Post, March 14, 1984.)

It was a milestone moment for Jackson and for black politics. His best showing was in Georgia, where he won 21 percent of the statewide vote — the best a black candidate had ever fared in a binding presidential primary. He hit the matching fund threshold and also cleared a more informal barrier with black voters who hadn't known what to make of his candidacy. As the race moved on, Jackson won increasingly large shares of the black vote, powered by grassroots energy and pride that blunted the impact of Mondale's endorsements.

The Jackson campaign also featured an extensive voter registration drive, which increased black turnout and changed the composition of the Democratic electorate. In New Jersey, for example, black voters represented 20 percent of the June Democratic primary electorate — nearly triple the 7 percent they'd accounted for in 1980.

Jackson ended up winning more than 3 million votes nationally, almost 20 percent of all cast in primaries, with outright victories in Louisiana and the District of Columbia. He had exceeded expectations.

For black leaders who'd snubbed him in the primaries, there was fallout. At the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, Coretta Scott King and Young entered a gathering of black Jackson delegates only to be serenaded with boos. "I respect him for what he did 20 years ago," one of the delegates said of Young, "but 20 years later, things are not so good." ("Jackson Rebukes Hecklers," Milton Coleman, The Washington Post, July 19, 1984.)

Jackson enjoyed not just the media spotlight but also his new leverage.

He could now act as a broker on behalf of black voters, and Mondale, as the Democratic nominee, felt pressure to accommodate him, fearful of alienating a growing Democratic constituency. Jackson sought and won a change to delegate apportionment rules, which would increase his clout in a future campaign. And he was given a prime-time slot at the convention, where he delivered an emotional speech and punctuated it with this promise: "God is not finished with me yet!"

#embed-20190604-black-votes-nav-footer iframe {width: 1px;min-width: 100%}