Meet the Swiss league that's the antidote to football's super rich

Home to capitalist bemouth FIFA, you might not think of Switzerland as a hotbed of sporting socialist activity.

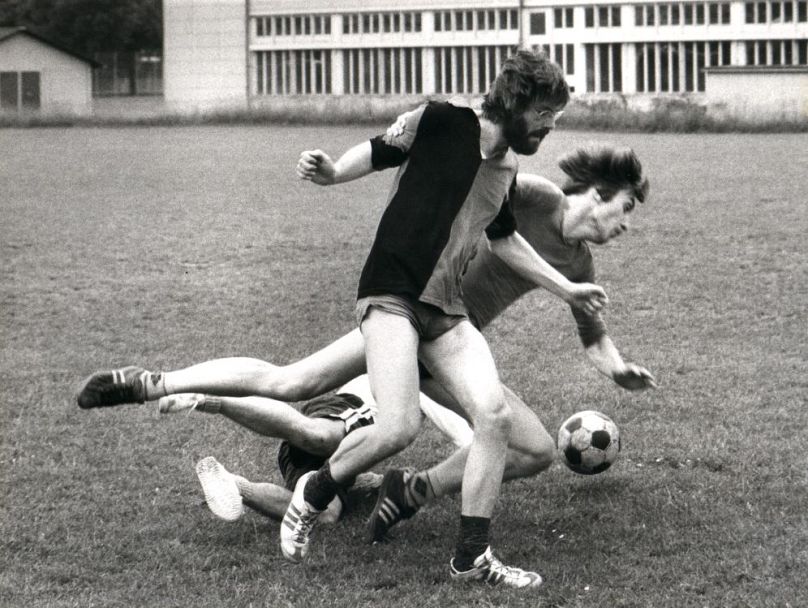

But back in the 1970s, some revolutionary leftists in Zurich transferred their ideals to the football pitch.

They created an alternative football league that shunned commercialism. Referees, league tables and uniform football kits – even boots – were also dispensed with. Every game was self-regulated.

In a climate of fragmentary leftist politics, leading light Giorgio Bellini aimed to unite the disparate factions of Swiss ideology, if not on the streets, then on the pitch.

Christoph Kohler, historian and writer of the documentary film “Ein Tor für die Revolution” (A Goal for the Revolution) says: “When the league was founded in 1976 it was a bad time for young left-wing people.

“The revolution and spirit of 1968 was gone… most of the progressive people figured out that the best thing was not to change the world but to change the way of living, of loving, of working, of education. And even the way to play football.”

“Football was at this time very conservatively organised with old structures,” he added. “So, some left-wing activists of Zurich decided to start their own football federation.”

The Fortshrittliche Schweizerische Fussballverband (FSFV) or Progressive Swiss Football Association was born. It is the oldest alternative football league in the German-speaking world and also the best known.

However, it was not long before their alternative kickabouts fell under the radar of the state security forces.

The Zurich Office of Sport handed the memberships required to use the pitches directly over to the police.

Their official diktat read: “Since Fall 75, some of the left-wing groups have been playing football against each other. After requesting the Zurich sports office to allocate a sports field they were asked to send in their statutes and membership lists.”

The authorities did not apologise until decades later.

As the movement began to establish itself with its ideals intact they declared that: “In the FSFV now is the time to strike! If the players are not playing athletically or if fairness is being sacrificed to win at any price, he may demand a break in the game and discussion.”

Yes. He. Not particularly progressive. Although football is a very male-dominated game wherever it is played, Kohler mentions that, at the beginning of the league, most teams had women integrated into their teams.

Kohler maintains that this was an ‘important political issue’ of the league and that teams would not be dictated to by age and gender but by “the joy of playing rather than winning”.

However, this noble practice did not really carry through with men dominating the league.

In 1980 left-leaning Swiss women formed their own female-only team, which eventually dissolved before making way for an all-female championship in 1999 which still exists today.

By the turn of the millennium, alternative leagues also sprang up in other German-speaking Swiss cities such as Basel, St.Gallen and Berne.

Once home to Lenin and Reformation theologist Zwingli, and the birth of counter-cultural movement – Dada – Zurich was the natural home of the movement.

Today the FSFV is bigger than ever and more successful than ever.

Although Kohler says there are still some teams ‘with a clearly left-wing ambition’ the political issues have taken something of a backseat.

Sechy Andreas, at the FSFV, declares that “we are definitely a non-commercial organisation”, and instead of FIFA’s army of staff it is maintained by volunteers.

The league is still self-organised and non-profit which in an era of footballers commanding eye-watering sums and displaying debatable pitch behaviour makes it positively Trotskyist.

Although Switzerland’s national football team is controlled by the Swiss Football Association its players flirted with nationalistic politics during the 2018 World Cup.

Its players of Albanian heritage – and even one that wasn’t – made the sign of the double-headed eagle which is the national emblem in a nod to the once highly-troubled Balkans region.

It is clear that whatever the league you play in you cannot keep Swiss football players away from politics.