The governments of several African countries are using Internet shutdowns more and more to control what people say or do online. How can regular citizens defend themselves?

What would you do if your government decided to intentionally shut down your access to the Internet? Millions of people around the world have had to answer this question time and time again over the past few years, as government-mandated Internet blackouts are on the rise.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Less than a month into 2019, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon and Zimbabwe have experienced government crackdowns on Internet connections.

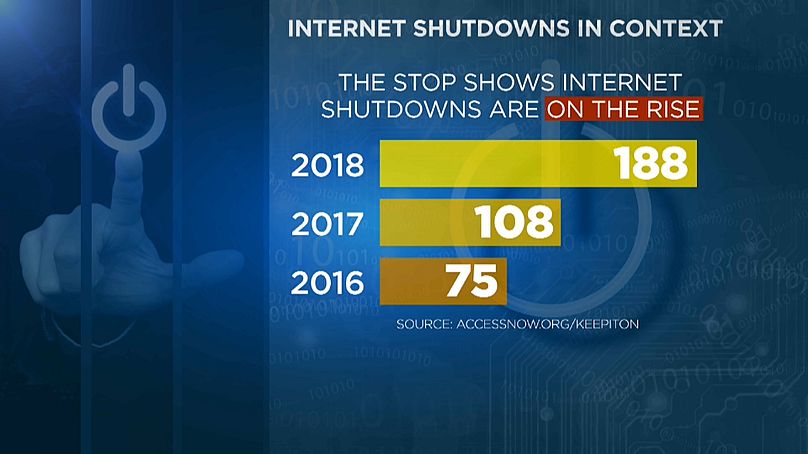

From 2016 to 2018, 371 separate cases of Internet shutdowns were documented around the world. More than half of them occurred last year alone, according to international non-profit organisation Access Now.

Authorities have used a number of reasons to justify the blackouts, including public safety, national security and stopping the dissemination of rumors and illegal content.

However, advocacy groups investigating governmental tendencies to exert control over the flow of information don't buy it. They claim it has more to do with silencing opposition movements and protests and trying to limit political instability.

"They harm everyone: businesses, emergency services, journalism, human rights defenders, and demonstrators. They don’t help victims or restore order," Access Now's website reads.

What countries have resorted to Internet shutdowns in the past?

In the past few weeks, several African governments have turned to partial or complete shutdowns in attempts to control the public discussion.

Sudan doubled down on social media amid widespread anti-government protests, with Access Now and the #KeepItOn coalition calling on network operators to fight back against state pressure — but it wasn't the only African country to do so.

Zimbabwean authorities were quick to gag social media — including Facebook and Whatsapp — as soon as civil unrest over rising fuel prices spread in Harare and other major cities, and the DRC also ordered a full blackout following recent elections.

The first official Internet shutdown in Africa happened in February 2007 in Guinea, when former president Lansana Conte blocked access to the country's four main Internet service providers.

Prior to that moment, authorities simply resorted to arresting journalists or shutting down specific websites. But the foundations for the practice were really laid out by former Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak in 2011, after he cut access to all Internet and SMS services amid escalating tensions.

From 2016 to 2018 alone, Africa witnessed 46 Internet shutdowns, weighing on the freedom of expression of citizens as well as on the countries' finances. Some of them only lasted a few hours, others went on for days. In the anglophone regions of Cameroon, where the Internet was inaccessible for citizens for 230 days between January 2017 and March 2018.

Chad, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, Somaliland, Algeria, Togo, Cameroon, Gambia, Uganda, Gabon, Algeria, Morocco, Lybia, Tunisia, and Algeria have all cracked down on their citizens' access to the Internet in the past.

How did citizens react to Internet or social media shutdowns?

"People always find a way", Zimbabwean analyst Alexander Rusero told Euronews.

Faced with an Internet shutdown after protests over rising fuel prices escalated, many of his fellow citizens relied on VPNs, downloadable private networks that enable users to send and received data across shared or public networks. "But it doesn't work for everyone", Rusero pointed out. "Usually the ones in Harare, at the centre of the country, manage to".

The analyst was quick to underline the issues behind similar crackdowns. "People look for alternatives and turn to gossip", he explained: "During the Internet blackout there were a lot of lies and rumors — they spread faster than you would believe. Media relies on social media, and so do critical opinion leaders. Outside those platforms, fake news manifest".

Jean-Hubert Bondo, a journalist from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, doesn't believe the problems end here.

"Many Congolese families live off their small cybercafés. Also, we are in a country where there are not enough physical libraries. Students and researchers use the Internet to research their work at the university. Young people animate pages on Facebook and WhatsApp", he told Euronews. "To deprive us of the Internet is to take us back to antiquity".

As for the VPNs Rusero mentioned — the most common ways to avoid Internet censorship worldwide — Bondo said that, during the latest shutdown, they failed to work.

"We were totally cut off from the world", he said. "Some of us were forced to move to neighbouring countries, like Rwanda, Congo-Brazzaville, and Zambia to get a connection. Only the major institutions and international organisations had their Wifi connection".

In response to what is being perceived as a violation of human rights, Bondo reported that several Congolese civil society organisations have now lodged a complaint against the main telecommunication companies.

In Uganda, a crackdown on Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, YouTube, and mobile money apps in February 2016 as citizens were heading to the polls sparked a legal case that will be discussed in court in February 2019.

"Shutdowns may not silence people, but they do hinder communication", said Ugandan blogger Ruth Aine Tindyebwa.

"So many people were inconvenienced — but the Social Media Elite still got online via VPNs."