Venezuela exodus: 'People are leaving in order to survive'

As thousands of people leave Venezuela because of the deepening economic crisis, Euronews maps out where the migrants are going headed — and how it's affected the countries receiving them.

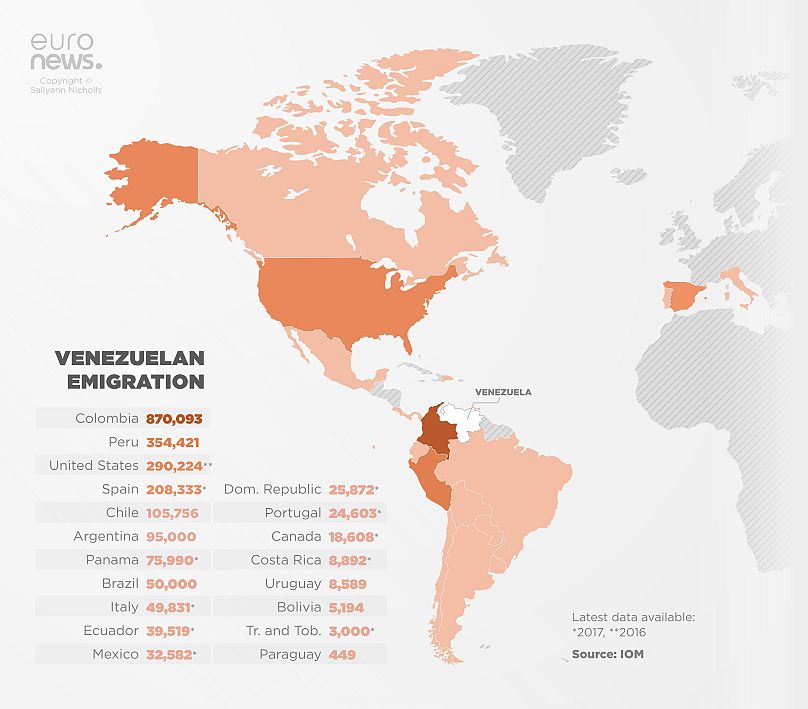

An economic crisis has weighed down Venezuela since 2014. Faced with hyperinflation and a shortage of food and medicine, many Venezuelans have decided to leave their country by plane, boat, or even by foot. The UN's International Organisation for Migration (IOM) estimated that 2.3 million Venezuelans have left their country, with more than 1.5 million living in other South American countries.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Yet the numbers are expected to rise. "The figure is likely to be higher as most data sources do not account for Venezuelans who crossed borders informally and are with irregular status," warned the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

The exodus Venezuela's experienced since 2014 is one of the biggest mass displacements in the history of Latin America, said Luisa Feline Freier, an assistant professor of social and political sciences at Universidad del Pacifico in Peru.

"In terms of scale, it's definitely comparable to the Syrian exodus and there's a chance the Venezuelan exodus will surpass the Syrian one," she said.

The latest figures show that there are more than 5 million UNHCR registered Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and North Africa.

'People are leaving in order to survive'

Unlike Syrians, Venezuelans are not leaving because of an armed conflict in their country.

"I interviewed migrants a couple of months ago and they told they hadn't eaten anything except starch mixed with water because they could not afford to buy rice," said Freier. "(What's happening in Venezuela) is a humanitarian crisis beyond imagination. People are leaving in order to survive."

As hyperinflation makes the local currency worthless, Freier said, people are forced to sell everything to afford a bus ticket out of the country.

"A bus ticket to Peru is about 130 dollars, so people sell everything to buy a ticket and we know that those that cannot afford it have started walking to Peru," said the professor.

Where are Venezuelan migrants mainly going?

With the US being a popular destination in previous years, most Venezuelans are now migrating to neighbouring countries, data from IOM shows.

Colombia has been the main country to receive the Venezuelan migratory flow. The IOM estimates that around 870,000 Venezuelans were in the country as of late July 2018

In recent years, however, migrants have continued south towards other regional countries, with Peru, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, and Ecuador being other popular destination countries.

In Central America, Panama is the country that received the most migrants, according to 2017 figures.

Migrants with greater financial means have fled to faraway destinations like the US and Spain.

IOM figures recorded more than 208,000 Venezuelans living in Spain in 2017 and some 290,000 in the US in 2016.

These are estimate numbers and they do not capture those in irregular situations or in transit.

Asylum applications by Venezuelans

Figures by the UNHCR show that over 117,000 asylum claims were filed by Venezuelans in 2018 — surpassing those from 2017.

Peru's government had received more than 126,000 asylum applications in June 2018 (since 2014) — the highest number recorded this year, followed by the US with more than 72,000 and Brazil with around 32,000.

Other forms of legal stay

A number of countries in the region have arrangements outside the asylum system for Venezuelans to reside for an extended period (one or two years) with access to social services, which include temporary residence permits and work visas.

According to the UNHCR, Colombia gave out the most legal residency permits to Venezuelans (181,472) in 2018, followed by Ecuador (83,435) and Argentina (77,936).

Venezuelan mass migration is creating tension in the region

According to Freier, Colombia is facing a serious "infrastructural challenge" with the great amount of Venezuelans crossing the border every day.

"Imagine one million migrants in Colombia — a country of a bit more than 49 million — compared to one million migrants in Germany (which has a population of around 82 million)."

"For Colombia, a country that has less means that Germany, to deal with this kind of crisis is huge."

Because of the mass influx, many countries have hardened their migration policies. Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru recently started asking for passports at border control. This, however, represents an "impossible task" for Venezuelans, according to Freier, because of corruption and a lack of paper.

"Getting a passport can take months if not years."

Earlier this month, Ecuador declared a state of emergency due to an unusually high volume of Venezuelans crossing over the northern border with Colombia.

Freier argues that as the number of Venezuelan migrants increases, the xenophobic sentiment does as well and it provides a platform for conservative political actors to deliver anti-immigration discourses similar to those in Europe.

"I spoke to many Venezuelans in Peru who said that the discrimination in Colombia and Ecuador was so bad that they chose to move to Peru. Many said Ecuador was fine until there were too many Venezuelans and public opinion shifted and in Peru, they felt very welcome until the latest xenophobic backlash," she said, adding that there's a real need for integration policies.

And what about the international response?

For Freier, the international community is not doing enough to help the plight of exiled Venezuelans.

"For the longest time there was a lack of interest in the topic and it's only recently that more media outlets started reporting on it and thereby raised awareness."

"I think more needs to be done in direct assistance to migrants but also in terms of developing integration policies and a regional response," the political science professor added.

As experts and the UN warn that the Venezuelan exodus is building toward a "crisis moment" similar to events involving refugees in the Mediterranean, officials from Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru will meet this week in Bogota to seek a solution to the crisis.