For most of us, the sky is the limit. However, for astronauts no such restriction exists, the whole galaxy is within their reach. For Professor Stamatis Krimigis, is seems that boundary lies at the end of the universe.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Speaking at this year’s TEDx Athens symposium in Greece, Prof. Krimigis, who has played a key-role in some of the most important space missions over the last half a century, explained why there are no limits to the exploration of the universe.

Prof. Krimigis spoke exclusively to euronews about the past and future of space exploration as well as the importance of science and technology, particularly during the tough economic times that many are facing today.

Who is Prof. Stamatis Krimigis

Born in 1938 in the village of Vrontados on the island of Chios, Greece, Stamatis Krimigis is a Greek-American scientist specialising in space exploration. He has contributed to the majority of the United States’ unmanned space exploration programmes of the solar system and his work includes assisting with exploration missions to almost every planet in our system.

In 1999, the International Astronomical Union named the asteroid 8323 Krimigis (previously 1979 UH) in his honour.

Krimigis emigrated to the US after attending school in Chios. He studied at the University of Minnesota, earning his Bachelor of Physics in 1961. Later, in 1963, he earned his Master of Science at the University of Iowa and his Ph.D. in Physics in 1965.

He was a student of James Van Allen, the space scientist that played an instrumental role in establishing the field of magnetospheric research in space. Van Allen discovered Krimigis after his publication on the diffusion of solar flare protons. Today, the publication is known as the ‘Krimigis Diffusion Model’.

Krimigis is Head Emeritus of the Space Department Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University Laurel, Maryland, USA. He is also a member of the Academy of Athens, Greece, where he holds the Chair of ‘Science of Space’ and is the President of the Greek National Council for Research and Technology. Among other missions, he was part of the scientific team that contributed to the launching of Voyager 1, the only manmade object to have entered interstellar space. He has published more than 350 papers in journals and books; he is also a fellow of the APS and AGU and a member of the International Academy of Astronautics where he serves on the Board of Trustees.

euronews: From the ‘Krimigis Diffusion Model’ to Voyager 1, you have always been keen on discovering the unknown. Did you start out simply because you liked stargazing?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: Well, all of the above is true. Certainly, where I grew up on the island of Chios we didn’t have light pollution, and I could look at the stars and see the planets. And, I always wondered, ‘what goes where’, and ‘why do they move the way they do’? But then, the point is to have the opportunity to do something about that, and my opportunity was going to the United States to go to college and meeting my mentor, Professor Van Allen, who was of course the pioneer of the American Space Program. He invited me to go to his laboratory to study with him as a graduate student and, as they say, the rest is history.

Voyager 1 at the Kennedy Space Center

euronews: Nothing that is ever accomplished in the scientific field comes easy. Which one of your accomplishments do you consider your greatest and why?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: In retrospect I have to say it is what happened a year ago when Voyager 1 crossed the boundary between our solar system and the galaxy. And I say retrospect because of course we observed a lot of new things and made many discoveries with Voyager at Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune. But, in terms of historical significance, being part of a mission that crossed the boundary between our solar system and the galaxy has to be the most important thing Voyager has done.

euronews: For most of us the sky is the limit. For you, what is the boundary?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: I believe that if had thought of limits when we were designing these experiments and these missions then we would have stopped far short of where we ended up being. Limits essentially are placed on the basis of current knowledge and current technology and if you don’t go beyond these, you are never going to make progress. In some ways I consider that as a cop-out. I do not know if you know that phrase in English, but what it means is that we all set a limit and once we get there we can relax. And that is not the essence of discovery and it is not the way progress is made. You have to set sights beyond any considerable limits when you start out.

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis

euronews: Well known scientists like you are considered role models for young people. If you had to give them just three pieces of advice, what would they be?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: It is a good but tough question. Above all, I would say to a young person that you should have a vision and believe in a dream and pursue it. So that’s number one. You should never lose sight of what you really want to do in the long term. The second thing is of course you’ve got to be absolutely dedicated and hard-working if you are ever going to achieve any kind of dream. Because without hard work you are never going be able to take advantage of any opportunities you may have in the future. The third thing is that you have to question absolute knowledge. Our school books are full of these statements and certainties about nature and technology and the universe and that only describes the state of affairs when the book was written and sometimes not even that. So, if a young person does not question what is “canned” then I do not think progress in science and technology would be made. We have to question existing knowledge.

euronews: During your speech in Athens TEDx 2013, you asked for more team spirit in Greek society. Do you believe that is essential so that Greece can move forward and leave the crisis behind?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: I believe that team spirit lacks in this country. A different methodology is needed. We have to realize that unless we work together in a team we are never going to get out of this downward spin. It is absolutely essential for the recovery of a country. I have to say that I am beginning to see at least a degree of voluntarism in Greece that did not exist five years ago. But that is not enough. We need to realise that we have to work together as a team not as individuals. That’s absolutely essential.

euronews: In your opinion, in order to overcome the crisis, could Greece turn to science and technology? And would this stop the brain drain taking place today?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: Excellent question again, because we have several examples of countries that were in dire straits many years ago and they decided to change their policies and embrace technology and innovation as a way out. The best documented example is that of Finland. They lost all their markets at the end of the Cold War. Their gross domestic product (GDP) dropped by something like 20 to 25%. At that time, what they decided to do is to upgrade their university system and devote 3% of their GDP to research and technology. They have essentially the best university system in Europe right now. They do exceptional work. You touched the base that I am very keenly interested in and working on right now. I am chairman of the National Council for Research and Technology of Greece (ESET). In fact our term is ending at the end of the year. One of the things that we have done is to put together a strategic plan for research and technology. We recommended, and apparently the government has accepted, that the percentage of the GDP devoted to research and technology ought to rise from 0.5% to 1.5% of GDP. In other words, our intention is to triple it between now and 2020. And the European Union is trying to get it to 3%. We set a goal, just half of that of European Union’s, but it’s a lot bigger than what it is now, which is only 0.5%. We think that it is essential for the country to really begin to progress rapidly and sharpen its economy with small and medium enterprises that use high technology.

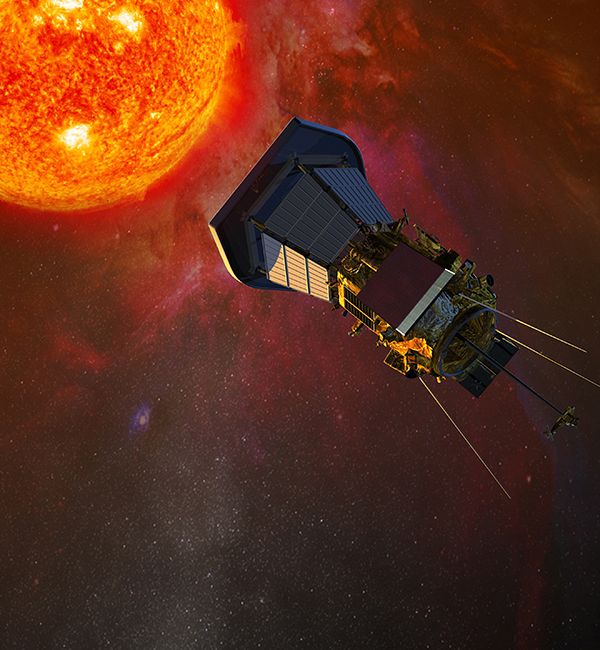

Solar Probe Plus

euronews: As a person who has taken part in so many important moments in the history of mankind, do you feel you have fulfilled all your dreams?

Prof. Stamatis Krimigis: I never feel satisfied with what I have done. And that is why I am still working 60 hours a week and doing many jobs. The next thing that I am looking forward to is to launch a spacecraft, which we are working on right now, to investigate the Sun. That is scheduled to go up in 2018. Again it is going to be a pioneer mission because we get within 6 million kilometres of the surface of the Sun. The temperature on the outside of the spacecraft is going to be about 1500 degrees Centigrade (Celsius). We hope to survive that and I will give a report in 2019.

Watch the video