A united Ireland was once perceived as a nationalist dream. Today it’s about economics, opportunity, and a return to the European Union, Emma DeSouza writes.

Northern Ireland’s power-sharing government has been restored, with pro-United Ireland parties now holding both the office of First Minister and leader of the Opposition.

Unionism — the political force that advocates for Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom — is in steady decline; How close are we to a United Ireland?

Looking at the present political landscape, in every electoral office the vote share for political unionism has decreased, while nationalist party Sinn Féin has surged to become the largest party in both local and national government.

By contrast, Northern Ireland was established with an inbuilt protestant majority with unionism as the dominant political power for the best part of a century.

Former Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Craig once referred to Northern Ireland’s government as a “Protestant parliament for a Protestant people”.

The political change is a manifestation of wider shifts in demographics. In 2021, Catholics outnumbered Protestants in the census for the first time in history.

That same census provided some interesting insights into identity with an 8% drop in British identity over the course of 10 years, down from 722,400 to 606,300, while Irish and Northern Irish identity increased.

This means that today, in terms of political, demographic, and national identity, Northern Ireland appears to be less British, and less unionist, than ever before.

The kingmakers are already there

How that plays out in polling is mixed; In 2022 Northern Ireland-based polling company LucidTalk showed 41% of respondents would vote for a United Ireland today, for those aged 18-24, that number increased to 57%.

In 2023, polling by the Institute of Irish Studies/Social Market Research showed 47% would vote to remain in the United Kingdom.

Polling has not demonstrated majority support for a United Ireland, but neither has it shown majority support for remaining in the United Kingdom. There is a considerable portion of the electorate who “don’t know”, and who will ultimately be the kingmakers in the event of any vote.

On the ground, there has been a sharp increase in preparations for a border poll. Academically, University College London now has a working group on unification referendums on the island of Ireland, Ulster University in Belfast is researching gendered perspectives on constitutional change, and University College Dublin is examining constitutional futures after Brexit.

Universities across the UK and Ireland are undertaking considerable study into a border poll, precipitated by the increase in public debate.

The politics are shifting, too

At a civic level, the beginnings of pro-union and pro-unity campaign groups are already there.

Former First Minister Arlene Foster launched the Together UK Foundation, a pro-union group that is working to “proactively inform and engage debate on the benefits of all parts of the UK”.

On the pro-United Ireland side, there is the civic group Ireland’s Future. Established in 2017, the group has released several publications and held conferences across the island of Ireland.

Political parties are also preparing for change. In 2020, the Irish government launched the Shared Island Unit, which works to build reconciliation, understanding, and cooperation on the island, while the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) launched the New Ireland Commission, a participatory structure that seeks to engage people on the shape of a New Ireland.

Sinn Féin has also been working on the ground, hosting a series of so-called People’s Assemblies, while Ireland’s second chamber Seanad Eireann launched a public consultation on constitutional change.

The times, they are a-changin'

A decade ago, the idea of a United Ireland seemed fantastical; it was but a side note in political debate and did not feature as a part of everyday discourse.

Today, a week does not go by without an event, radio segment, or newspaper column on a United Ireland.

Polling may not yet confirm it, but all the other indicators suggest that Northern Ireland is changing at pace and that rather than a possibility, a vote is now firmly on the horizon.

The tenure of Sinn Féin's Michelle O’Neill in Northern Ireland’s top office will be critical, and should she be joined by her counterpart Mary Lou McDonald, who polls indicate may be the next Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland, then timelines may speed up even further.

One of the greatest gifts of Northern Ireland’s peace process is that it removed identity as a contentious issue, providing people with the space to view their own identity, and belonging, through multiple prisms.

A united Ireland was once perceived as a nationalist dream. Today it’s about economics, opportunity, and a return to the European Union — that alone will appeal to more than just traditional nationalists.

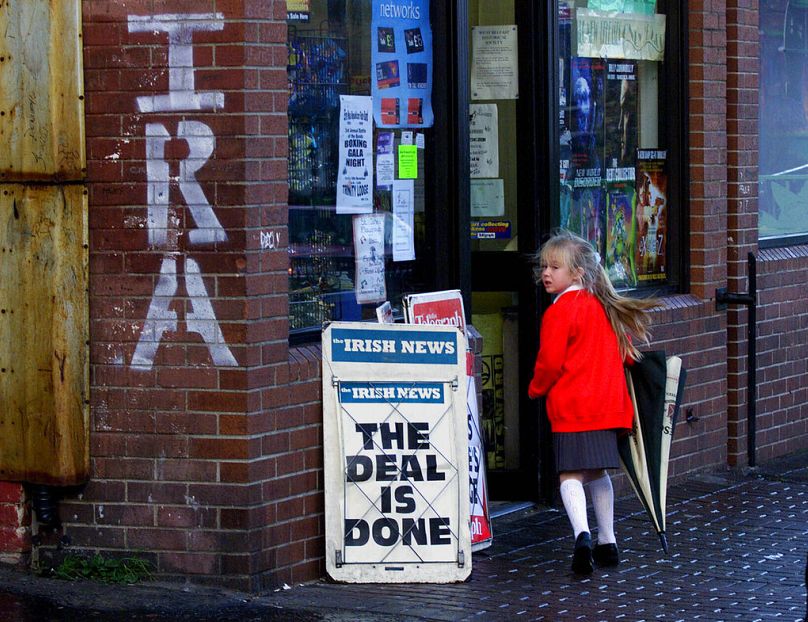

The Good Friday Agreement enshrined the democratic means for answering a question that has plagued Northern Ireland since it was formed; should Ireland be one? An answer is on its way.

Emma DeSouza is a writer and political commentator based in Northern Ireland.

Contact us at view@euronews.com to send pitches or submissions and be part of the conversation.