Analysis: Warren's embrace of the ambitious health care overhaul ran afoul of her political base at the wrong time.

WASHINGTON — Elizabeth Warren, whose presidential fortunes were on the upswing just months ago, is out of the race. She rose to the top of the field with strong debate performances, an anti-corruption message, and a popular plan to tax the ultra-rich.

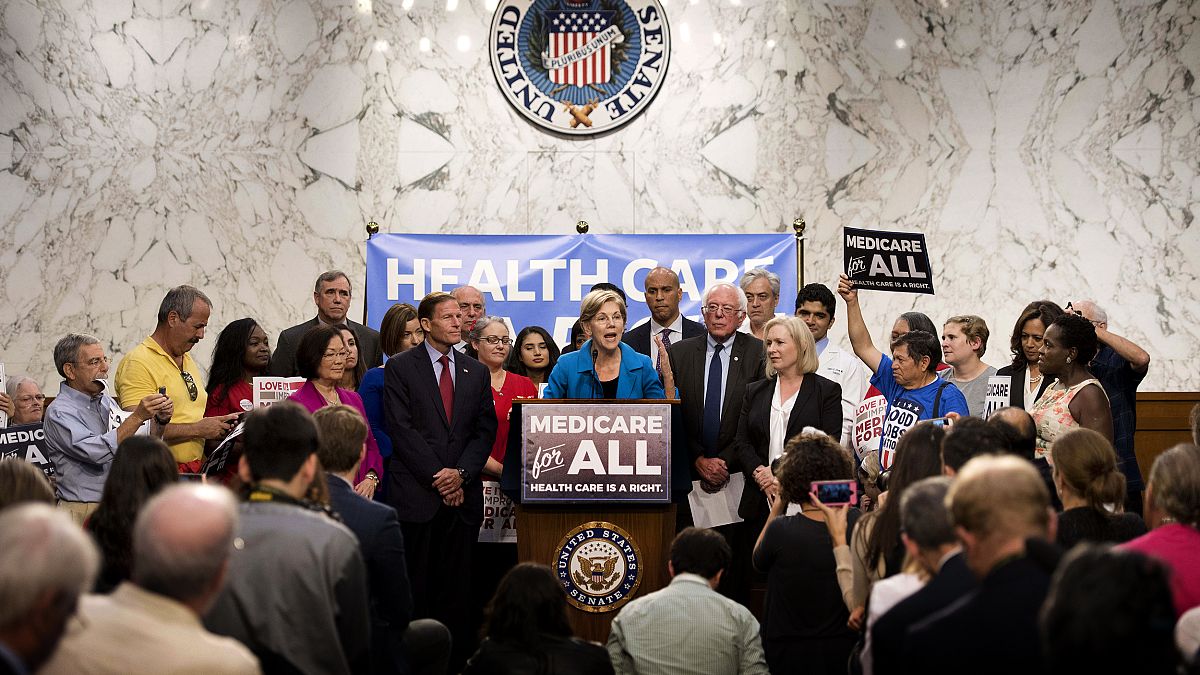

Then Medicare for All happened.

For months, the Massachusetts senator faced constant attacks over her embrace of Bernie Sanders' single-payer health care plan, then further attacks after she released her own plans on how to pass, finance, and implement it. Her campaign was dragged down and never fully recovered.

Meanwhile, the Vermont senator, who "wrote the damn bill" on Medicare For All while offering fewer details on how it would operate, surged and is now in a two-way race with former Vice President Joe Biden.

Why did their fortunes diverge? It's a question Warren supporters have been asking for months.

Many Democrats sympathetic to her campaign see a sexist double standard at play, in which a female candidate was expected to have all the answers while a man could skate by with broad talk of revolution.

"The fact that Warren paid a penalty for laying out the specifics of her Medicare for All plan and that Senator Sanders has never paid such a penalty is a sign of the challenges women face at this moment in politics," Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, said.

But when it comes to Medicare for All, the two candidates also had different bases, different messages, and different vulnerabilities, all of which might partially explain their different outcomes.

Both politicians are known as progressive icons, but Warren's support was more concentrated among college-educated Democrats. Sanders continued to win over the youth vote while trying to build a broader coalition of blue-collar and anti-establishment voters demanding systemic change.

Sanders started with a loyal foundation of support from 2016 that he has never relinquished. Warren's rise in the polls, by contrast, was slow and gradual as she sought to tamp down concerns about electability.

Warren branded herself as the "plans" candidate early in 2019 and her campaign began to take off, led by her call for a wealth tax on "ultra-millionaires" that she estimated would raise trillions of dollars for new social spending programs.

The wealth tax was an instant hit, not just with the Sanders left, but with the upwardly mobile voters who would become her base. She promised to use the new revenue to fund benefits with clear appeal to upper middle-class and lower-income families alike, including student debt cancellation, free public college, universal child care, and universal pre-Kindergarten.

"When you're a progressive, you always have the centrists and pundits asking, 'how will you pay for it?' And she took that whole talking point off the table," Rebecca Katz, a progressive Democratic strategist who supported Warren, said. "It was a policy that the majority of Americans could get behind, and then it allowed for all the big ideas that came after it, from student debt to universal child care, which were paid for by the wealth tax."

In championing the wealth tax, Warren moved past Obama-era debates about raising income taxes on merely well-off families making over $250,000 a year, and instead started the threshold at fortunes of $50 million or more. Rather than pit the 99 percent versus the 1 percent, she called for uniting both against the 0.1 percent.

In doing so, Warren found an overarching message well-suited to the times. It turned out that the increased concentration of wealth in Americaboth provided a juicy tax base and created resentment and economic anxiety even among so-called "winners" in the economy, who still felt squeezed by the rising cost of living.

"The media narrative is that they're affluent, but many suburban households are struggling with child care and college affordability," Sean McElwee, co-founder of the progressive think tank Data For Progress, said. "She showed what an agenda that could really appeal to the suburbs looked like."

Polling indeed suggested a wealth tax had real legs with voters not only outside the left, but outside the Democratic Party, which helped her gradually overcome initial voter concerns that she was a general election liability. Even a CNBC poll of millionairesfound majority support for her plan.

Primary voters took notice and by September, a YouGov pollof Democratic voters found they considered Warren just as electable as Vice President Joe Biden.

But her initial platform was also notable for what it was missing: a health care plan.

For months, she had refrained from offering a specific plan on health care, instead echoing rhetoric from candidates like Pete Buttigieg that there were "a lot of different pathways" to achieve Medicare for All's goals.

It was only at the first Democratic debate in June, well into her rise, that she tied herself to the very specific approach envisioned by Sanders. "I'm with Bernie on Medicare for All," she saidafter raising her hand to indicate she would abolish private insurance plans in favor of single-payer health care.

As the months wore on, however, it became clear Medicare for All didn't fit the winning formula that underscored the rest of her platform.

Rather than simply taking from the ultra-rich, Medicare for All involved rerouting trillions of dollars in existing health care spending. Instead of handing voters a new benefit they didn't have before, it asked them to accept major changes to their existing health care based on more nuanced arguments, all of which were contested by rivals and industry groups.

This was especially problematic for Warren, because the college-educated voters most attracted to her wonky populism were also the voters most likely to have coverage through work. Polls show Americans are mostly satisfied with their work plans, even as they worry about the overall system.

Warren sought to rebut these concerns, arguing her plan would allow the government to negotiate lower prices from drug and hospital companies, reduce overhead from insurers, and provide relief to families worried about rising medical costs.

But she faced increased pressure from rivals and the press to explain how she would pay for and implement Medicare for All, which Sanders had not fully answered in his bill.

"Everyone else could have different plans," Katz said, "but she had to explain every single thing on every single plan because she was perceived as 'The Candidate With Plans.'"

Warren tried to stick to her winning formula — tax hikes on the rich, benefits for everyone else — and released a plan with (arguably) no direct tax increases on the middle class. But the proposal was greeted with skepticism by critics not only to her right, but to her left, including Sanders himself.

This left Warren in a difficult spot. She had taken a risky position to win over voters on the left, but they remained attached to Sanders. Meanwhile, her competitors to the middle correctly guessed that her voters were easier to peel off than Sanders' hardcore base, and relentlessly attacked her on the issue.

Facing bipartisan fire and more scrutiny in the press, Medicare for All grew less popular as voters learned more about its price tag and elimination of competing private plans.

The biggest damage to Warren on Medicare for All might not have been about policy details at all, however, but that the fight revived concerns about her electability among soft supporters. Majorities of Democratic primary voters still supported Medicare for All in exit polls, but they also are focused on beating Trump and Warren's decline suggested some were nervous about putting the issue front and center in a general election.

By late January, a Quinnipiac poll found that only 7 percent of Democratic voters considered Warren the most electable nominee, down from 21 percent at her October peak. For Sanders, whose longtime supporters were all-in on Medicare for All and unmoved by the new round of attacks, the number was 19 percent.

Warren supporters won't get to test their theory of how Warren would perform in a general election in 2020. But the lessons from her rise and fall might inform future candidates looking to push the party to the left.

"She added a lot of important ideas," McElwee said."Showing there are viable ways to do progressive taxation that people should not be afraid of is powerful."