His face is one of the most recognisable in the world but back then, it had been 24 years since the last photograph of Mandela had been published. Few people knew what Mandela looked like, let alone what kind of man he had become. And now here he was, standing before me, his hand outstretched.

By Stefan Simanowitz

“I’ve dreamt about this moment for more than half my life,” Janey Halim, a long-time anti-apartheid activist, whispered to me as Nelson Mandela approached us down the line.

The year was 1993 and I was a recent graduate, in South Africa to work for the African National Congress (ANC) as it transitioned from liberation movement to political party and ultimately, to government.

Although he had been expected, news that Mandela had arrived at the shabby headquarters of the ANC Western Cape caused great excitement. I hurried from my office and watched from the open corridor that overlooked the car park as his small entourage emerged from their Mercedes. Our regional head, Tony Yengeni, was there to open the car door. I looked down as a pair of polished shoes appeared, followed by well-pressed trousers and then, finally, the man himself.

Looking relaxed and elegant, Mandela was ushered into the building. On the first floor, staff and volunteers hurriedly formed ourselves into rag-tag line, our eyes fixed on the stairwell at the end of the corridor. For each of us, Mandela represented something deeply personal: the embodiment of hopes and struggles that we scarcely dared to speak aloud.

And then he appeared. Taller than I had imagined. Aged 75 at the time, he was slim with a powerful, dignified presence. He started making his way down the line of activists, speaking to each in turn.

For me, Madiba, as he was affectionately known, had been part of my consciousness for almost as long as I could remember. As a child visiting South Africa, I would lie on my fold-out bed on the balcony of my grandparents’ flat looking out across the dark ocean at the dimly burning lights of Robben Island and think of him. At school, I had done projects on apartheid and for so many years I had marched and protested and campaigned.

In 1990, when news broke that Mandela would be released, I went I straight to Trafalgar Square in London to celebrate, and the following day I stayed glued to the TV screen for the first glimpse of him. Today, his face is one of the most recognisable in the world but back then, it had been 24 years since the last photograph of Mandela had been published. Few people knew what Mandela looked like, let alone what kind of man he had become.

And now here he was, standing before me, his hand outstretched.

“This is Stefan who works in our press office,” said Tony Yengeni. “He is from London.”

“Ah, from England,” said Mandela fixing his smiling eyes on me and shaking me warmly by the hand. “What brings you to our country?” I explained briefly how my parents were originally from Cape Town and how I had been active in the anti-apartheid movement. “Thank you for being here,” he said, pausing for a photo before moving down the line. I did not see him again for almost a year.

It was nine days before the election and, although the ANC knew the Western Cape was not a winnable—in the end it lost to the National Party by almost 40 percent—it was decided Mandela should come to Cape Town for some final meetings and a rally. I was responsible for arranging the media, first at a photo-call with schoolchildren in Green Point Stadium, then at a political meeting at Grassy Park and finally at a stadium event in Athlone.

Arriving at Greenpoint Stadium on that sunny morning, I was there to meet him and his team. When he saw me, Mandela smiled and, without missing a beat, asked: “How is England?”

But a day that had started brightly ended in tragedy when a stampede in Athlone Stadium resulted in the deaths of three people and more than a dozen injuries. As news of the calamity filtered out, one of my seniors was concerned about how it might play out in the media. “I can see the headlines now,” he lamented. “They’ll be asking how the ANC can run the country when we can’t even organize a rally”.

But Mandela’s concern was not with the media impact. His only thoughts were with those killed and their families. He immediately changed his evening plans in order to visit the injured in hospital. He had no need for spin doctors to instruct him as to what would appear to be the right thing to do. He knew it instinctively.

After polls had closed on election day Mandela was in reflective mood. “I should be jumping for joy but I just feel a stillness,” he reportedly told a friend. “There is so much responsibility. So much to do.”

A week after the election, I was in Pretoria for Mandela’s inauguration, a day which he dedicated “to all heroes and heroines in this country and the rest of the world who sacrificed in many ways and surrendered their lives so that we could be free. Their dreams have become reality. Freedom is their reward.” On that heady day in 1994, it felt as if anything was possible: that, together people really could change the world.

And perhaps that is one of Mandela’s most enduring legacies. Through his integrity, courage and strength he showed by example what a single individual can achieve, and in so doing he instilled the belief that injustice, whether large or small, can be defeated.

Over the next two decades, I saw Mandela from afar several times. I watched as he and the Queen danced at the party he threw at the Albert Hall in 1996 and again at his 90th birthday celebration in Hyde Park in 2008. In 2010, I was back in South Africa to mark the 20th anniversary of his release. Aged 91, he was too frail to come to the commemoration outside the gates of Victor Verster Prison, but he did make a brief appearance in parliament.

Speaking that day outside the prison gates, Cyril Ramaphosa, then deputy president, told a small crowd that "as Mandela walked through these gates we were also being set free."

But the significance of his release was felt far beyond South Africa's borders. In a world that was only just emerging from the shadow of the Cold War and undergoing a rapid and uncertain period of transformation, Mandela's release gave a renewed sense of hope and optimism. As the writer Breyten Breytenbach wrote at the time: "Perhaps there is now a little more sense to our dark passage on Earth."

Although it did not come as a surprise, news of Madiba’s death in December 2013 nonetheless hit me with an unexpected force. I felt an immense void—both personally and for the world.

Delivering the annual Mandela Lecture yesterday, Barak Obama drew on Mandela’s legacy to remind his audience that “the struggle for basic justice is never truly finished” and urge them not to give into cynicism. "We've been through darker times. We've been in lower valleys,” he said. “I believe in Nelson Mandela's vision…I believe in a vision of equality and justice and freedom.”

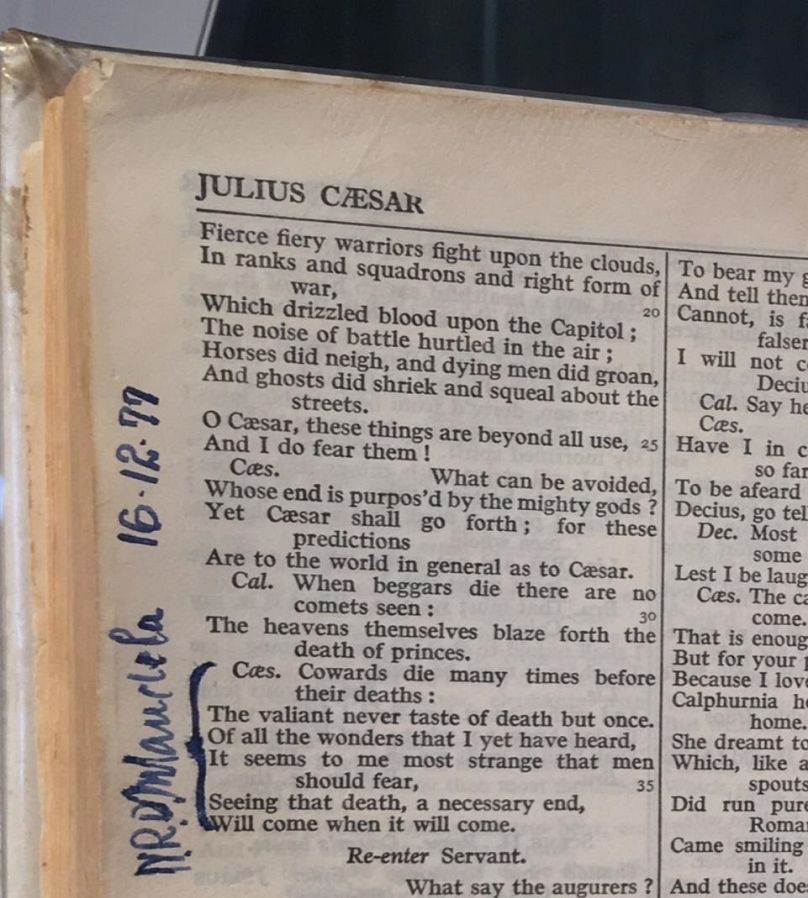

This week, at the opening of the Mandela centenary exhibition in London, I came across Mandela’s copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare. The book was open at Act 2 Scene 2 of Julius Caesar and one passage was marked in the margin with Mandela’s name and the date, December 1977.

“Cowards die many times before their deaths. The brave experience death only once. Of all the strange things I've ever heard, it seems most strange to me that men fear death, given that death, which can't be avoided, will come whenever it wants.”

Stefan Simanowitz worked for the ANC from 1992 until 1994, in the ANC Western Cape’s Department of Information and Publicity.

Opinions expressed in View articles do not reflect those of euronews.

/This piece first appeared in Newsweek/