Residents were forced off properties and protestors bullied off properties ahead of World Cup

On the opening day of the World Cup, Mariya Petuchova wasn’t thinking about football, even though she was out with friends only a few kilometres from one of the venues. She’d just been handed a sheaf of documents relating to her trial, due to begin in 24 hours at the Kaliningrad District Court.

The furniture designer, 34, was accused of participating in an illegal demonstration against the inauguration of President Vladimir Putin in the city’s Victory Square on May 5. The next day she received a fine of 200,000 roubles (€2,735)

She found out about the charges during an evening out. Having left her friends inside the Tabasko café on the same square as the protest had taken place, she popped outside for a smoke only to be approached by two men.

“They showed their documents for a second, which I didn’t manage to see, and forced me into a blue minivan with no signs on it and brought me to the police station,” recalls Petuchova, who subsequently spent a sleepless night in a cell.

No protests

Whilst the eyes of the world may be on Russia, it doesn’t mean they can see things from the perspective of people like Petuchova. Like many other cities, Kaliningrad, which hosts group stage encounters between Nigeria and Croatia and Serbia and Switzerland, has banned all protests until 10 days after the end of the tournament.

“We love football, but the way money is being spent on the World Cup makes us sick,” Petuchova complains. “We’d very much like to share information with the arriving fans about how hotels are being built and main streets are being repainted using money for healthcare, or how ordinary people suffer because of the construction, but we’re not allowed.”

Burned and repossessed

Another resident set to harbour unpleasant memories of the World Cup is Natalya Strezhniova. The middle-aged lawyer takes Euronews to a site where she once owned a plot of land. She wanted to take a photograph of the location of her former summer house. However, she’s unable to find it. The entire territory was buried under sand and covered by the stadium’s car park.

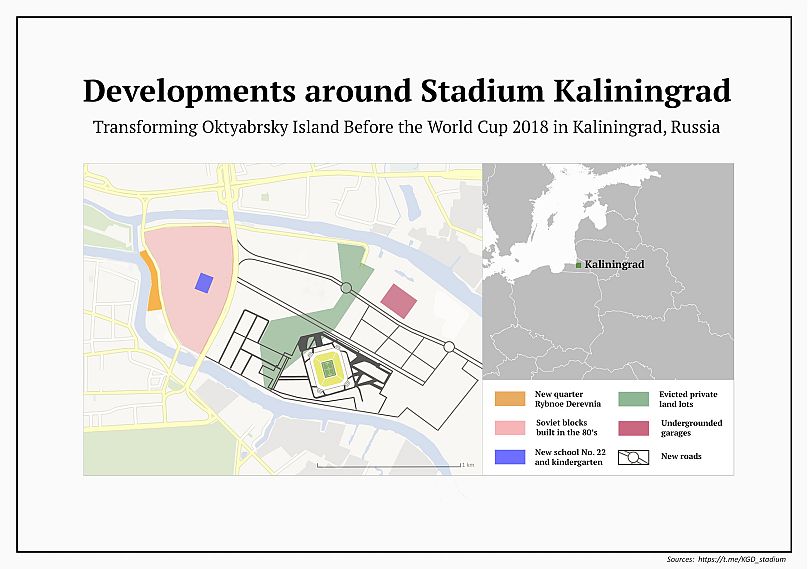

Strezhniova represents a community of around 90 landowners who were evicted from the area.

“Even if they were just summer houses and even if they were in a really poor condition, the government doesn’t have the right to act in such a disgusting way,” says Strezhniova angrily.

“One evening, some big young guys poured fuel on my house and set it on fire. The next morning, workers with permits ’to destroy buildings in an emergency state‘ were already pulling down my house. I filmed everything!” she recalls.

Glancing around the newly created desert, she tries to make sense of the situation: “We don’t want to ruin the atmosphere. The World Cup is an enormous event and our problems are very small”.

But she says that after many sessions at the arbitration court, she and other landowners have received just half the market value of their land. When they applied for compensation for their summer houses they were asked: “What? You want money for that too?”

A renovation boom

The exclave of Kaliningrad became part of the Soviet Union after being taken from Germany at the end of the Second World War. It remains the only year-round ice-free port in Russia and has further strategic importance due to its location wedged between the European Union member states of Lithuania and Poland.

The city’s new football stadium was built on Oktiabrsky Island, known to the locals as Ostrov. The sandy desert around the stadium stretches out in three directions. It’s dotted with white tents housing security, ticket and media centres.

One kilometre away are a series of apartment blocks built by the Soviet Army in the 1980s, the first major attempt to impose a purpose on the swampy island between the two branches of the Pregolya River. Damp and crumbling, they’ve met the same fate as many similar construction projects in the area ever since. Around 70 buildings in the city are currently declared “avariny” or condemned.

Zhenia, who lives nearby, spends her retirement chatting with friends and sitting on a bench near a monument to the Soviet Navy. She didn’t want to give her last name. She says most people who live there want to be evicted to find a better place to settle.

When the construction of the stadium began, the houses on the street closest to the stadium named after General Pavlov were flooded. The incident attracted media attention and turned the condition of the buildings into a national issue.

In the following months, the most dilapidated homes were renovated, including that of Aleksandr Janin, a young father who recently found work installing the lifts inside the stadium.

Putting down his lunch of bread and sausage on a child seat in the back of his car, he tells Euronews that the World Cup has definitely brought benefits to the area: “There’s been an abandoned construction site in the centre of our district for as long as I can remember. Recently they turned it into an enormous complex of kindergartens and primary schools with pools.”

However, some of the work has been more cosmetic than effective. Although his house was insulated and painted, no work was done on the inside and the original draughty windows remain. Are the houses falling down? “No, they’re not. But all of them have problems”. He claims that the land on the island is constantly subsiding, and because of this the ground beneath the stadium had to be raised six metres. “My garage on the other side of the island was above ground level two years ago and now it’s underground,” he notes.

Good business for some

An area of German Revivalist architecture called Ribnaja Derevnia (Fish Villlage) hides the island’s residential district from the eyes of fans visiting the stadium. Andrej Aksinin, General Manager of the company Gala Stroy, has an office just behind it, only yards from where his construction career began laying a pavement.

In 2018 he received a number of significant state tenders that he links directly to the World Cup. “My company grew from 12 to 50 workers in just three years,” he points out, acknowledging that not everyone has done so well.

The boom that grew Aksinin’s business has left its mark on Kaliningrad. The facades of the five-floor 'Khrushchev' Soviet apartment blocks are being transformed into German Romantic maritime cottage lookalikes. The city is teaming with commercial and residential construction sites.

Pockets Full of Sand

However, the biggest construction project, and the one which is attracting the attention of millions of football fans this month, has become synonymous with scandal.

The contractors responsible for building the so-called Kaliningrad Stadium are locked in a legal battle over blames for delays and problems with quality, with some involved even facing corruption charges.

Regional governor Anton Alikhanov, who arrived in 2015 at the age of 30, says that since his arrival the problems have been contained and the city can now look to the future.

“There are no problems on the island. The stadium is standing, right?” he responds to Euronews’ questions. He wants to build more notable landmarks including a museum and concert hall. And alongside tourism, he’s planning to renew the economy.

“At this moment a project establishing an offshore zone on the island is being prepared,” Alikhanov remarks, expressing hope that the project will be deliberated in the Duma very soon. After citing the Isle of Man in the UK and Delaware in United States as models for his vision, he declares: “We’ll create such a zone around the stadium.”

His confidence finds echoes down the road in the city’s other ground where the biggest game in the local league, last seasons’ champions Olimpiia v Kalingrad 2018 attracted around 30 fans. Among them are Oleg, Ivan and Valera, who proudly announce that they’ll be attending World Cup games as FIFA volunteers as the tickets, even with discounts for locals, were too expensive.

“We found out about the World Cup in Russia 10 years ago and we’ve been waiting for it our entire lives. That is cosmic!” His companions’ vision of the competition’s legacy is simple: “We’ve got a very good governor who cares about football. … He’ll still care about it after the championships.”