10 key questions on Brexit, two years on from the UK's vote to leave the EU and in the run-up to a crucial Brussels summit.

This month marks two years since the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Ongoing negotiations between the British government and the European Commission reach a crucial point at the end of June at an EU summit in Brussels.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Arguments have raged: between London and Brussels, “Leavers” and “Remainers”. Economic orthodoxy has been pitted against increasingly important themes such as identity and culture. Key points have become lost in the war of words as the process drags on.

To help cut through the fog, here are Euronews’ answers to 10 key questions (they may be updated regularly as events unfold):

1 Where is this interminable process at?

The UK voted by 52 to 48 percent to leave the European Union – an economic and political partnership of 28 countries – at a referendum in June 2016. Prime Minister Theresa May triggered Article 50 of the EU’s Lisbon Treaty in March 2017 to set in motion the formal two-year process towards Brexit. The United Kingdom is due to leave the EU at the end of March 2019.

The June summit has been billed as a deadline for the UK to produce answers on key unresolved questions, but there are fears this will slip until the autumn.

By then both sides hope to reach a draft deal on future ties. This would then be put to the European Council’s 27 national leaders at a summit in October. At least 20 countries representing 65 percent of the EU’s population, as well as the European Parliament, must approve it.

The UK Parliament must also approve a final deal. British Prime Minister Theresa May’s flagship Brexit legislation has been going through the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

The largely pro-EU upper house has inflicted several defeats on the government, sending its plans back to the elected chamber. There, the government’s precarious situation has made it vulnerable to internal rebellions from rival camps with opposing visions of Brexit.

2 What does each side want?

Two years after the referendum, the UK is still wrestling with a fundamental question over Brexit. The extent to which it should seek to diverge from EU rules and standards, and risk sacrificing the benefits of close ties, has sparked a monumental political debate. Brussels has repeatedly accused the British government of lacking clarity over its aims.

Brexiteers say it’s about taking back control of the UK’s laws, money and borders. At the same time, Theresa May has said she wants the UK and the EU to remain close partners.

After taking office, the prime minister pledged to end the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the UK, to end “free movement” for EU citizens into the UK, and to stop Britain’s “vast contributions” to the EU budget. The UK intends to leave the EU’s single market – which involves accepting free movement – but wants the best possible access to it via a new free trade agreement with the EU.

Britain also seeks freedom to strike free trade deals with non-EU countries – which means leaving the EU’s customs union, as this ties members in to EU policy in imposing common external tariffs.

The European Union’s objective has been to preserve its own unity and the integrity of internal arrangements such as the single market and customs union. Leaders have consistently warned that these would be undermined if the UK is allowed to “cherry-pick” from the rules, or “have its cake and eat it” by benefitting from the advantages without accepting the obligations.

At the outset, the European Commission – mandated by EU leaders to conduct negotiations – quickly established priority issues concerning the UK’s departure to be resolved before future relations could be considered. These were the UK’s financial dues, the rights of EU and UK citizens, and avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

As for future ties, the EU wants a free trade agreement – without offering the UK the same benefits as membership – and a level playing field via an alignment of rules and standards.

EU leaders see Brexit as a damage-limitation exercise which balances the need to protect the economy and preserve good future relations, against the political imperative of ensuring the UK does not emerge better off from leaving the bloc.

3 What has actually been agreed?

Deadlock on the initial separation issues was broken in December 2017. Agreement was reached in Brussels on the UK’s financial settlement, citizens’ rights, and on the principles over Irish border arrangements.

An accord was then struck in March this year on a transition phase – May’s government prefers the term “implementation period” – to run from Brexit Day in March 2019 until December 31, 2020. Many existing arrangements will remain in place to allow time to prepare for, and determine, new rules. The UK will be able to negotiate new trade deals but they won’t come into force until 2021.

On money, the UK has agreed to pay into the EU budget as now until the current round ends in 2020. It may incur in future new liabilities agreed before then. The British government estimates the settlement will cost €40-45 billion.

Agreement to keep the Irish border open – with no physical infrastructure such as customs posts or cameras – was consolidated in March 2018 into a draft legal document. If all else fails, the UK will “maintain full alignment” with single market and customs union rules to guarantee no hard border.

EU citizens in the UK and Britons living on the continent will retain current rights to live and work on each side of the Channel right through the transition period until the end of 2020.

The record so far shows that London has made more concessions than Brussels. For instance, Theresa May has accepted that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) will continue to have influence in the UK, though it can no longer be the ultimate arbiter of the law.

4 Why is the UK in such a tangle over future EU trade and customs?

Details concerning the UK’s future trading ties with the EU go to the heart of the Brexit debate. The government is split – reflecting the ruling Conservative Party’s divisions – and weakened by its fragile position in Parliament.

Future customs arrangements have become one of the main Brexit sticking points. Under the EU’s customs union, countries impose a common tariff on goods coming from outside – which then circulate freely across national borders within the union without duties or checks. They cannot set their own import taxes.

Theresa May’s government is committed to leaving the customs union in order to pursue an independent trade policy and be able to strike deals with countries around the world.

For Brexiteers who want a clean break from the EU’s system, the question has become a litmus test on whether the UK is really ‘out’ of the EU. Pro-Europeans argue that some kind of customs union with the EU is necessary to avoid major disruption to trade and supply chains, inflicting serious economic damage.

The government wants trade with the EU to be as frictionless as possible but ministers have been unable to agree on a suitable customs model. They have been considering two possible options – a customs partnership and a “maximum facilitation” arrangement – but the EU has greeted both with outright scepticism.

The House of Lords has proved to be a thorn in the government’s side, passing amendments to its Brexit bill which will have to be considered when it returns to the House of Commons. They insist on a customs union arrangement and continued membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) – which includes full access to the European single market.

This raises the question of whether the UK could adopt a so-called “Norway model” – the non-EU country is a member of the EEA – but the government is hostile as it would mean accepting the free movement of people.

Opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn also rejects EEA membership for the same reasons, however his Labour Party has continued to soften its stance on Brexit. It wants a new customs union and now calls for “full access” to the single market, outside of full membership.

The politics concerning the various options are complicated, but the outcome will determine how smooth trade will be between the UK and the EU – as well as the nature of the Irish border.

5 Why does Brexit Britain need to do its own trade deals?

Leading Brexiteers such as Liam Fox and Boris Johnson argue that the UK surrenders its trade policy to Brussels if it remains in a customs union with the EU.

They say that being outside the EU will enable Britain to exploit new opportunities, with the trade secretary highlighting services and digital industries.

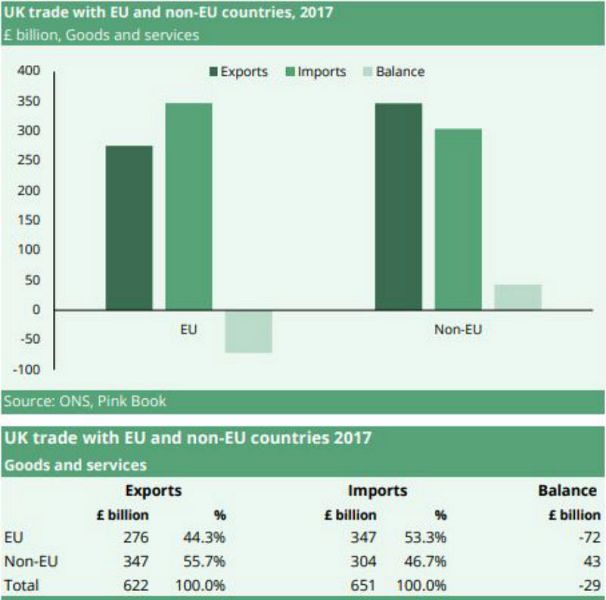

Johnson has argued that changing trade patterns make the EU less important for the UK. Figures show that the proportion of UK exports going to the EU has fallen over the past decade, although their value has risen.

The foreign secretary has cited the attraction of countries such as South Korea, where UK exports have doubled in recent years. Part of that success is due to the EU’s trade agreement with Seoul. After Brexit the UK risks losing such deals, although supporters say terms could still be applied.

The UK should be able to negotiate new trade deals more easily than the EU, they argue, because talks will no longer have to cater for more than two dozen countries’ special interests.

Several countries have been mooted as possible candidates for free trade deals with the UK, including the United States, China, India, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. It has been claimed, however, that some may seek significant concessions from the UK.

6 Why is the Irish border such an intractable problem?

The question of the UK’s future trade relationship with the EU is also relevant to one of the key goals agreed by both sides: avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland – part of the UK and in future outside the EU – and the Republic of Ireland, an EU member state.

During the 30-year “Troubles” of the late 20th century, the border was heavily fortified and a focal point for tension and violence. People and goods crossing it were stopped for customs and identity checks.

The 1998 Good Friday peace agreement paved the way for an open border. Security measures disappeared and the EU’s single market and customs union removed the need for inspections. However, political tensions remain between Irish nationalists and Northern Ireland’s unionists – which it’s believed could be inflamed should a hard border return – although some hardline Brexiteers believe the Irish border issue has been overblown.

With the UK intending to leave the single market and customs union after Brexit, the question of how to avoid border controls is unresolved. Brussels’ suggestion that Northern Ireland remain part of the EU’s customs territory has been rejected out of hand by Theresa May and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) – on whose support her government relies – as it risks creating another border between the North’s six counties and the rest of the UK.

The British government’s preferred solution is for a new free-trade agreement and customs deal with the EU, avoiding the need for border checks. Failing that, it believes technology and “trusted trader” schemes can be implemented. Brussels is nonplussed.

The prime minister’s latest proposal for a “backstop solution”, involving the UK matching EU tariffs temporarily, has prompted internal dissent in her Cabinet.

7 What other issues need to be resolved?

The draft treaty drawn up in March highlights more unresolved issues: they include governance of the Brexit deal and how to resolve disputes, the extent of ECJ jurisdiction in the UK, nuclear material, intellectual property, and security and defence cooperation.

The UK’s future access to Galileo, the EU’s satellite project, is uncertain. There is uncertainty over cooperation in scientific research. Brexit poses challenges for the UK over tax policy, particularly VAT.

Despite broad agreement on citizens’ rights, campaigners argue there is confusion surrounding the UK’s plans to give EU nationals “settled status” and there are fears that administrative problems may cause injustice.

The question also remains over whether UK nationals will have the right to retain EU citizenship after Brexit, giving them the right to travel, live, study and work throughout the bloc. A court case is pending before the ECJ.

8 What’s at stake for the UK economy?

There have been repeated warnings from business about the need for the UK to retain close access to European markets. In May a delegation of Europe’s biggest industrial companies met Theresa May and warned that they would not invest in Britain as long as uncertainty over Brexit persisted.

Government-commissioned economic analysis suggests being outside customs union would hit growth. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) has highlighted the need for single market access for services, which make up 80 percent of the UK economy.

The car industry in the UK and on the continent relies on integrated supply chains and frictionless borders. There’ve been reports that EU carmakers may seek to exclude British parts. The road haulage industry is worried about potential disruption.

The pharmaceutical industry is encouraged by the UK’s wish to keep close links to the European Medicines Agency, but question marks remain over practicalities.

The British government has promised an overhaul of farming subsidies, food production and the environment once the UK is outside the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The fishing industry is looking forward to taking back control of its coastal waters but will have to wait, as the UK will remain in the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) during the transition period.

Many businesses also want access to European workers and are concerned about future restrictions. Alarm bells have already rung over labour shortages in sectors from construction to the health service, tourism to fruit farms. Hostility to the free movement of EU workers was one of the main reasons for the referendum result, but the British government has still to unveil its post-Brexit immigration policy.

Reports quoting government analysis have suggested that some parts of the UK which voted strongly for Brexit will be most heavily impacted, if there is no deal.

The head of the UK’s customs service has estimated that even with agreement on the Brexiteers’ favoured customs plan, the bureaucratic cost to business may reach £20 billion (€22.8 billion) - a claim hotly disputed by Brexiteers.

9 Would ‘no deal’ be such a disaster?

Theresa May’s famous Brexit mantra is that “no deal is better than a bad deal”. “A no-deal scenario would be bad for everyone… but above all for the UK,” European Council President Donald Tusk has said.

For both sides, failure to reach a deal could bring economic, political and legal chaos at least in the short-term. No agreement could see the UK refuse to settle the withdrawal bill, blowing a big hole in the EU budget. EU citizens in the UK and Britons on the continent may find their status up in the air again.

On trade, World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules would apply. Tariffs would be imposed at varying rates. Experts say this would increase costs for UK importers and exporters, raising prices particularly for food. Border controls and customs checks would also increase costs.

Brexit supporters argue that the lack of an agreement is no barrier to trade, and the UK could cut or get rid of tariffs altogether. Boris Johnson has suggested the UK would “do very well” under such an arrangement.

Non-tariff barriers would hit services, which now operate across the EU via “passporting” rights. The UK would be outside EU regulatory agencies, threatening sectors such as pharmaceuticals and aviation.

The UK has been accused of failing to prepare for customs checks and a “no deal scenario” generally – even by some “Leave” supporters.

The EU knows that both sides would be damaged by a “no deal” scenario. Ireland especially, its economy so closely linked to Britain, could be particularly badly hit. It’s one reason why hardline Brexiteers argue that the UK should threaten to walk out of talks – to force Brussels to make concessions.

10 How has Brexit affected UK politics?

Brexit has been described as the United Kingdom’s most significant change since it joined the then European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973, and perhaps since World War II.

The fallout from the referendum has exacerbated tensions within the United Kingdom. Scotland voted heavily to remain in the EU, and the result revived questions concerning Scottish independence from the UK – which was rejected in a 2014 referendum. The Irish border conundrum is intensified by the fact that a majority in Northern Ireland wanted the UK to stay in the EU.

Theresa May’s position has been weakened since her government lost its majority in the June 2017 general election. It’s now propped up in Parliament thanks to an agreement with Northern Ireland unionists from the DUP.

Arguably, the ruling Conservatives' internal divisions over Brexit have cancelled each other out and kept May in power. Both sides fear that toppling her might bring chaos – and possibly a hard-left Labour government under Jeremy Corbyn. Meanwhile the pro-EU Liberal Democrats remain a marginal force, despite the growth of a number of anti-Brexit grassroots organisations.

The consequences of Brexit are being felt on the continent too. The European Union is losing an existing member for the first time, along with a significant chunk of its budget. It’s a major test of the EU’s ability to withstand the rising tide of Euroscepticism – and calls into question the drive for closer European integration.

For more on the history of the UK’s troubled relationship with Europe, see our earlier four-part series here, here, here and here.