What happens when you raise the drinking age and restrict opening hours in a country renowned for its heavy consumption of alcohol?

On a Friday night a team of two police officers and three officials from the Drug, Tobacco and Alcohol Control Department (DTACD), carry out a number of raids in Lithuania's second largest city, Kaunas.

They aren’t looking for drug dealers, or tobacco smugglers but for vendors who are selling takeaway alcohol after 8pm. At the beginning of the year, the government introduced the strictest alcohol laws in the European Union, raising the legal drinking age from 18 to 20, restricting opening hours for off licenses and banning all advertising for beers, wines and spirits.

The DTACD is responsible for enforcing the new rules.

The first target is a store, one of dozens that open in the evening to meet demand from late-night shoppers and which pose the biggest challenge to the new restrictions. The shop's banner, 'Broliai Juodvarniai' (the Blackbird Brothers) glimmers in the shade of the neighbouring Soviet-era communal apartment blocks. Every few minutes people leave the shop with two or even four glasses of alcohol in their hands. Near the shop, the Blackbird Brothers have built a tin shelter and equipped it with plastic furniture to comply with the law which allows consumption on the premises through the evening, but nobody wants to stay. There’s no heating and inside the temperature is around zero.

After 8pm through the week and 3pm on Sunday, all vendors have to pour any alcoholic drink into a glass before selling it and insist that clients do their drinking on the premises. To comply with the requirements, night shops have made more or less convincing transformations into bars. Beer, wine or vodka is served in half-litre containers with a €2 deposit designed to discourage customers from wandering off. It doesn’t always work, but the Blackbird Brothers do what they can. Violating the regulation can cost them a fine of between €150 and €1,450.

During the authorities’ two-hour check-up, dishevelled and intoxicated crowds force themselves through the door. One, named Vaclovas, shares his thoughts: “I hate the new rules because sometimes I just can’t help myself. What do I do if I finish work after 8pm?”

He turns to those waiting behind him and yells out: “Turn around, there’ll be no alcohol here tonight.” All leave disappointed. Most of them are loyal customers, even though alcohol here has become more expensive and buyers now get a fine of between €14 and €30 if they are caught leaving with their drinks.

The officer leading the raid, the head of the DTACD's Tobacco and Alcohol Control section Jurgis Kazlauskas, complains: “Vendors find their way around prohibitions easily and are eager to defend themselves in court. Check-ups require a lot of resources and cases can take up to a year and a half to come to court.” Since the beginning of the year, the DTACD has performed several such raids each week. Kazlauskas is looking for more effective ways to stop illegal alcohol sales, but for the time being, he's able to control only a small fraction of the trade. At midnight, in a deadpan manner, he presents the results of his evening’s in an interview with a local television station.

Rasa Lapinskienė, the owner of a bar in the centre of Vilnius called Plumbum, says there is no sign that heavy drinkers are changing their habits and moving to the more controlled environment of licensed premises. “People who want to get drunk in Lithuania still usually choose night shops over bars,” she said.

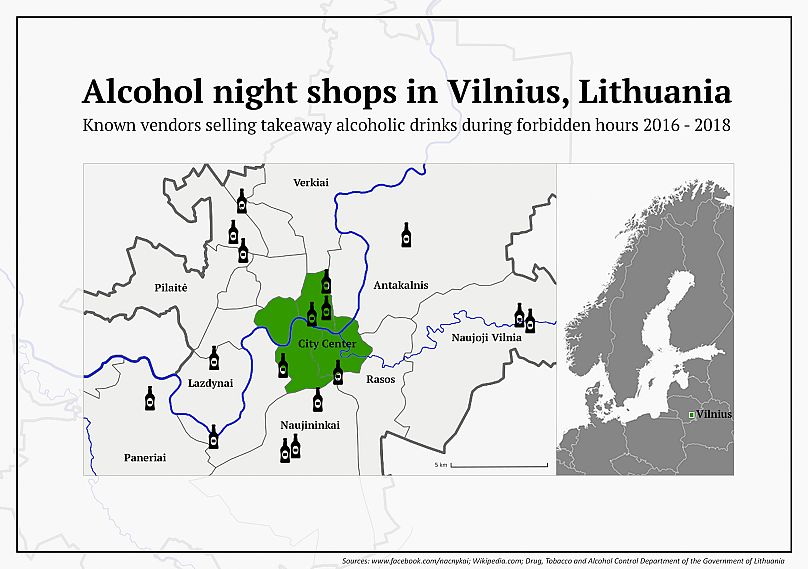

In Lithuania, night shops, known colloquially as nachnykai, are a long-standing tradition. According to the DTACD there are around 20 shops selling alcohol illegally in Vilnius and Kaunas respectively. In Vilnius, there’s one selling takeaway alcohol 50 metres from the doorstep of the mayor’s office.

Facebook trade

The DTACD's next catch is a dealer selling beer and brandy on a Facebook group. Using the nickname Mikas Kekenonas he posted a picture of a selection of drinks with a message ‘Delivery in Kaunas’ just after 8pm.

In January, groups selling alcohol out of hours with names including 'Alco 8pm+', 'Alcohol in Kaunas' and,'Help 24/7' proliferated on Lithuanian social media. A glance at the profiles of their members suggests most of them may be under-age.

Some sellers claim they can deliver the goods to your doorstep in exchange for a few euros. Others act more carefully and offer to lend alcohol to be returned later. For each post offering alcohol, there's another requesting a drink. Messages such as ‘Anyone in need in the centre?’ or ‘Does anyone have normal vodka?’ appear alongside posts asking to buy beer on behalf of teenagers.

A 19-year-old male by the name of Kakenonas sold two bottles of Napoleon brandy for €20 each to a fake buyer. The head of Kaunas’ Police Prevention Department Joana Gudelytė, who led the operation, treats him with sympathy. She offers the minimum €150 fine.

The brandy has Polish excise stamps. It was probably bought for around €7 in one of Poland’s low-cost Biedrionka supermarkets on the Lithuanian border.

Shops stocking alcohol in neighbouring Poland and Latvia are crowded with Lithuanian buyers. The legal age in those countries is 18 and there are no border checkpoints. Prices are also three times lower. After an increase in the Lithuanian alcohol excise tax in 2017 the Alko 1000 Market chain opened a branch in a former border checkpoint post in the town of Grenctāle. Recently, the Lithuanian retailer Vynoteka has opened shops in the Polish border towns of Suwalki and Sejny. Last summer it offered its customers a new free service, namely alcohol shopping trips to Poland. Rather than delivering the drinks to the customer, the customer is delivered to the drinks.

Under 20s bar ban

Since January 1 it's been illegal for anyone under the age of 20 to drink alcohol in Lithuania. However, many 18 year olds who are still at school claim they drink and don’t have any problem buying alcohol.

In the middle of February, students celebrate 100 days before their graduation. After the official ceremony at a prestigious school in the centre of Vilnius, young adults go out to celebrate on with friends. Andrius, 19, doesn’t mind sharing his thoughts on the new legal drinking age: “They think young people are stupid. We all have ways to get alcohol. I drank before I was 18. It was much more interesting because it was forbidden.”

Kotryna, Greta and Laura from the same school answer the question how they get hold of alcohol today in one unanimous voice: “We don’t have any problems purchasing it, we'll manage somehow. We haven’t put too much thought into it yet.”

A black-suited youngster who wished to remain anonymous maintains: “The law doesn’t matter to me at all. I'm not joining the party because I'm driving today.”

Most of Vilnius' nightlife locations don't bother asking for ID. It’s too much hassle. However, a month after the laws came into force, new announcements about the legal drinking age are hanging on their walls. They state that it’s the responsibility of the bar owner to stop youngsters from drinking and it’s mandatory to ask for ID if the person appears to be under 25.

Vilnius bar owner Lapinskienė elaborates: “I know we have to ask for everyone’s IDs at the table, and if we have to we’ll need to employ a bouncer to keep those under 20 out.”

Many bar owners are starting to realise that the only way to avoid arguments is by denying entry to underage drinkers but their legal right to restrict entry is dubious. Mintautė Jurkutė, the Communications Manager for the Office of the Equal Opportunities Ombudsperson, thinks that banishing people over the age of 18 from entering a bar infringes on their rights. “If anyone would submit a complaint, we’d have to stop doing this,” she says.

Two perspectives

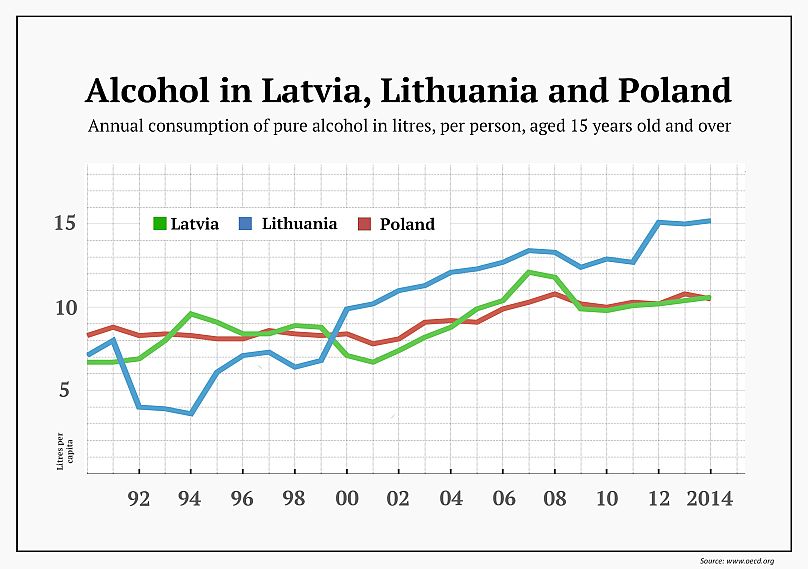

Alcohol consumption in Lithuania has been higher than in neighbouring countries for several years in a row. New regulations were, therefore, expected. However, two different opinions on how to tackle alcoholism and alcohol abuse have emerged.

In May 2017 a World Health Organisation (WHO) report presented Lithuania as the heaviest drinking country in the world, indicating that alcohol consumption would hit 18.2 litres per person per year without government action. The EU average is around 11 litres.

However, the debate has been fueled by local research institutions who have calculated using different methodology that alcohol consumption in Lithuania is steadily declining. Recently, preliminary results of a research project commissioned by the Lithuanian Business Confederation were announced in which it was stated that Lithuanians consumed no more than 12 litres per person in 2017.

These results are used to support two contradictory arguments. Vendors and the advertising industry claim that since there’s been no general increase, narrow regulations should be directed towards low-income groups living in the countryside where the problem is most acute. Supporters of the new regulations, however, insist that the problem is much bigger and that consumption has to be reduced using a wide range of measures.

Ona Davidonienė, director of the Lithuanian State Mental Health Centre, is sure that alcohol abuse and heavy drinking remains a major problem in Lithuania, citing its role in high rates of violent crimes, domestic abuse, road accidents and suicides in the country. However, she says changing attitudes is more challenging than just changing the law: "Enforcing these measures won't be easy, because many groups resist by all means available and some do it in a dishonourable manner."