‘God bless America.’

I mean that ironically. Not because the US has nothing to praise; on the contrary. Ironically because we generalists or we, the forgetful of historical struggles, don’t credit America enough for its contributions to socialism – the very word socialism makes even modern Americans aggressive. This isn’t only about their thinking. And don’t brand me a socialist, this is just a trickle-down of history.

Many good things we enjoy today around the world came out of America – that is obvious and undeniable. Yet these things are not restricted to ingenuity and high principle; important legacies we may take for granted are the result of others’ hardship. May Day is one of them.

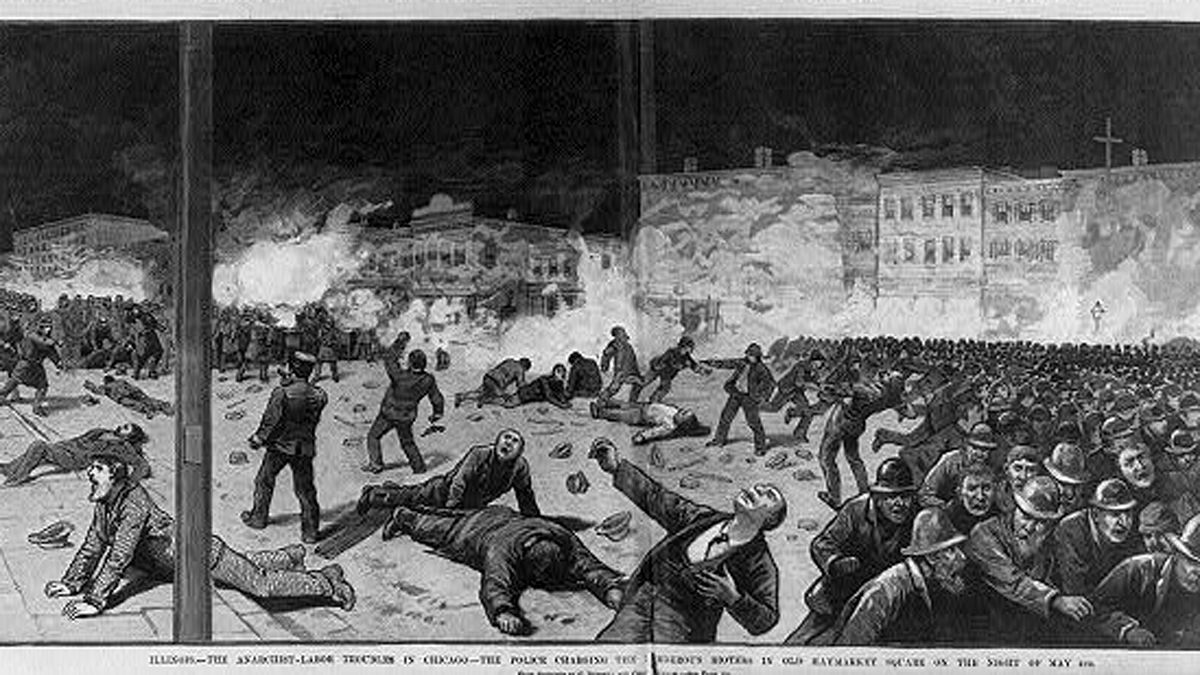

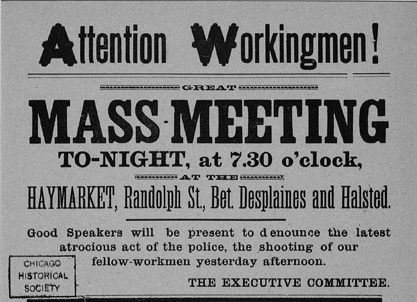

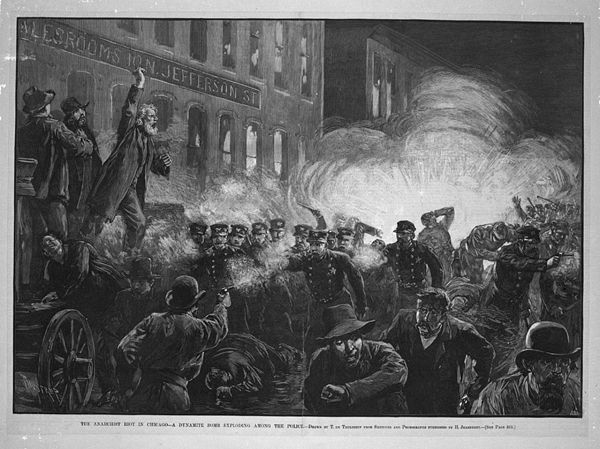

May Day is synonymous with International Workers’ Day. Originally, it commemorated the killing of some workers by police in a general strike in Chicago in 1886.

Rights for everyone were nowhere near part of the American Dream then. That term was coined decades later. As the period of spreading peace and prosperity approached – described alternatively in the US as a ‘Golden Age’ and in France (‘light of Europe’) as the ‘Belle Epoch’ – less fortunate ordinary people on both continents were suffering.

Wage slavery (meaning working for terribly low pay supposedly by choice but in reality because the alternatives were almost zero), economic exploitation in societies split into almost impenetrable layers… this was what allowed owners, resourceful entrepreneurs and the ruthless to amass wealth. Historically, this is normal.

But humanity was approaching a critical mass of not only increasingly distributable knowledge (education) but of social conscience. And that growing awareness was concentrating on notions that unequal bargaining power between labour and capital was unjust. Something had to give.

Those killings in Chicago happened barely 100 years after France had had its world-shaking revolution (1789–1799). They came 110 years after the United States Declaration of Independence, which pounded the table for people’s rights.

Its second sentence reads: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Well, was that naive?

Thank you ‘Creator’, but big industry wasn’t having it. Another revolution was under full steam by now: the Industrial Revolution (let’s say it lumbered to life between 1760 to 1840). Industrialisation may have put an end to feudalism in the old continent, with growing scientific knowledge and ideas of practical organisation, but it also harnessed capital (for the sake of simplicity, let’s say this is excess money in some form or another that the owner doesn’t need to use right now, and so can take his time deciding what to spend it on)… it harnessed capital as never before. This was capitalism.

Capitalism put people to work, productively. While they were working so hard, however, it was difficult to negotiate individually or collectively for fair conditions. Thinking about this fell mostly to non-workers, such as intellectuals, such as perhaps the most famous one, Karl Marx (German, 1818-1883).

A few years after the Chicago killings, in 1894 there were violent May Day demonstrations in Cleveland, as the US was sliding into a severe depression. The nation’s well-off (predominantly of the political right) became steadily warier of leftist politics and organised labour. (In Russia, the Bolshevik Revolution would not be long in coming.) But labour, against the odds, managed to organise.

The 1904 International Socialist Conference in Amsterdam called on proletarian organisations in all countries to stop work on May 1. Socialist, communist and anarchist groups were largely successful in making this official.

It is now a national holiday in more than 80 countries.

And in the United States (and Canada)? To soften the possible link with the Chicago killings, the US made ‘Labor Day’ in September the official day for workers’ celebrations, with May 1 to be celebrated as ‘Loyalty Day’.

‘God bless America.’