In the first in a series of articles on how World War II changed forever the countries that fought it, Ewa Dwernicki looks at Poland and the human and material destruction that forged the national psyche in the decades that followed.

The Katyn massacre

In Spring 1940 members of the Soviet secret police killed around 4,500 Polish army officers with a bullet to the back of the head and threw the bodies into a mass grave in Katyn Forest on the Soviet side of the border with Belarus. The killings were sanctioned by Stalin, whose wider plan was to eradicate any potential resistance to the Soviet occupation or communist ideology. In total an estimated 22,000 members of Poland’s ‘elite’, officers, doctors, teachers, engineers and students were massacred at various locations in the region. The mass grave in the Katyn Forest was first found by German troops after their invasion of the USSR and the discovery was a propaganda dream for the Nazi regime; Goebbels and his propaganda ministry would use the horror of the graves to depict the Bolsheviks and their Allied puppets as depraved monsters. The Kremlin denied responsibility, instead accusing the Germans of carrying out the massacre soon after they invaded the USSR in 1941. Keen to maintain the propaganda initiative the Nazis set up an international committee to investigate the massacre. The committee concluded it had taken place in 1940. A separate study by the Polish Red Cross made the same findings, which were sent to London but not published by the British government until 1989. The truth about the atrocity was kept hidden throughout the Cold War and the Soviets waited until 1990 to admit responsibility.

Even today the Katyn Massacre remains forged in the Polish psyche, a symbol of the worst crimes committed against Poland and the attempt to wipe out its most promising sons and daughters.

Holocaust: the horrors close to home

The Holocaust has had a universal impact on the collective consciousness and marked the memory and history of all countries. But for Poland the genocide led by the Nazis strikes a particular nerve as the killings were carried out on its own soil. Chelmno, Belzec, Treblinka, Majdanek, Auschwitz-Birkenau were once innocent fields and villages until they became infamous extermination camps.

Poland had the largest Jewish population in the world before WWII but after it, only 350,000 of those 3 million Polish Jews were left alive; the country had seen a part of its culture exterminated with them.

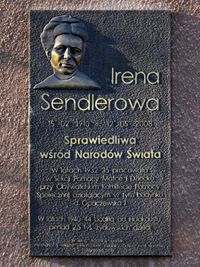

Non-Jewish Poles have been accused since the war of, at best, a lack of empathy and at worst, outright hostility towards their Jewish compatriots. The accusers point to the passive inactivity as thr Warsaw Ghetto burned in 1943 or the pogrom organised in Jedwabne while it was under Soviet – and not Nazi – occupation. But there were many Poles who themselves risked execution to help the Jewish population by hiding or feeding them. In Zegota, or ‘Council to Aid Jews’, Poland had the biggest (some would say only) organised movement in Europe that sought to support Jews against persecution. One member of the Home Army (AK) resistance group, Witold Pilecki, put himself forward to be detained at Auschwitz in order to provide details of the exterminations there to the Polish government in exile in London. It was his information that informed the Allies of the existence of Hitler’s Final Solution.

Even 70 years later Poland’s role in the Holocaust remains a burning domestic question that re-appears often in public debate.

Photos: monuments to Polish resistance heroes Irena Sendlerowa (left) and Witold Pilecki (centre) and to the infamous Jedwabne massacre (right).

Tehran, Yalta, Potsdam leave Poland in Soviet hands

Poland’s post-war destiny was decided at the inter-allied conferences in Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam, where the “big three” leaders of the USA, the USSR and Britain would discuss the country’s future borders and political regime. The military situation on the ground, where Soviet forces were beginning to overrun their German enemies, gave Stalin more bargaining power and he was able to win key concessions. It was decided during these conferences that after the war, Europe would be divided into “spheres of influence”. Not only did Poland fall into Soviet sphere, it also lost territory: Stalin wanted the new Soviet-Polish border to follow the Curzon Line, which meant the culturally significant cities of Lviv and Vilnius being absorbed into the USSR. The Polish government-in-exile was not informed of these decisions until much later when the decisions were almost faits accomplis. To compensate for land lost in the East, the leaders agreed Poland could annex German territory to the West and North. Millions of German citizens in these regions were forced out of their homes.

Politically, Stalin had promised Churchill and Roosevelt free elections in Poland with a national unity government open to pro-Soviet and pro-Western parties in the meantime. In reality though, communist-minded Polish parties supported by the Kremlin gradually took control of governing Poland and the free elections never materialised. Despite Churchill’s pledges to reward Poles fighting alongside the Allies on the Western front with a free Poland, the country spend most of the latter part of the 20th century under Soviet control.

The Warsaw Uprising

With the Red Army on Warsaw’s doorstep and Nazi officials being evacuated from the city, the head of the Polish Home Army, General Bor-Komorowski, was confident enough to launch the Warsaw Uprising at 5pm on August 1, 1944. The intention was to clear Warsaw of German troops and bring the government-in-exile back to take control before the Soviets arrived and did so themselves. The battle, the war’s biggest act of resistance against Nazi occupation, lasted 63 days. The Soviet army was just 10 kilometres away but did not intervene to help the poorly-armed Polish resistance effort. An estimated 18,000 Polish Home Army troops died along with a staggering number of civilians – up to 200,000, many killed in mass, summary executions. The head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler ordered that “the city must disappear entirely from the face of the Earth” and by the time the Wehrmacht left Warsaw, only 15% of the city it had not been destroyed. When the Red Army eventually entered what was left of the city, Stalin was able to establish the administration he wanted.

The failed Uprising left Poles feeling utterly abandonned, betrayed even by their so-called allies and left a lasting scar on the national consciousness. Air-raid sirens are still heard in Warsaw every August 1 at 5pm, followed by a minute silence.

Photos: (left) The Soviet Army observed the Warsaw Uprising from across the Vistula river; when they arrived into Warsaw proper, 85 percent of the city had been razed to the ground as part of a planned destruction (right)