Hundreds of volunteers have been working to connect footpaths in the UK, but the project could soon be international.

Daniel Raven-Ellison describes himself as a “guerrilla geographer”.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Over the last few years, he has walked across cities around the world taking a photo every eight steps, created a film showing the whole of the UK in 100 seconds, and worn a mind-reading device to ramble through national parks and cities.

Last year he successfully campaigned to make London the world’s first National Park City.

Before that, however, he was also my secondary school geography teacher. So, when a note about something called Slow Ways passed through my email inbox with his name attached, it seemed like a good chance to reconnect and have a chat about his most recent project.

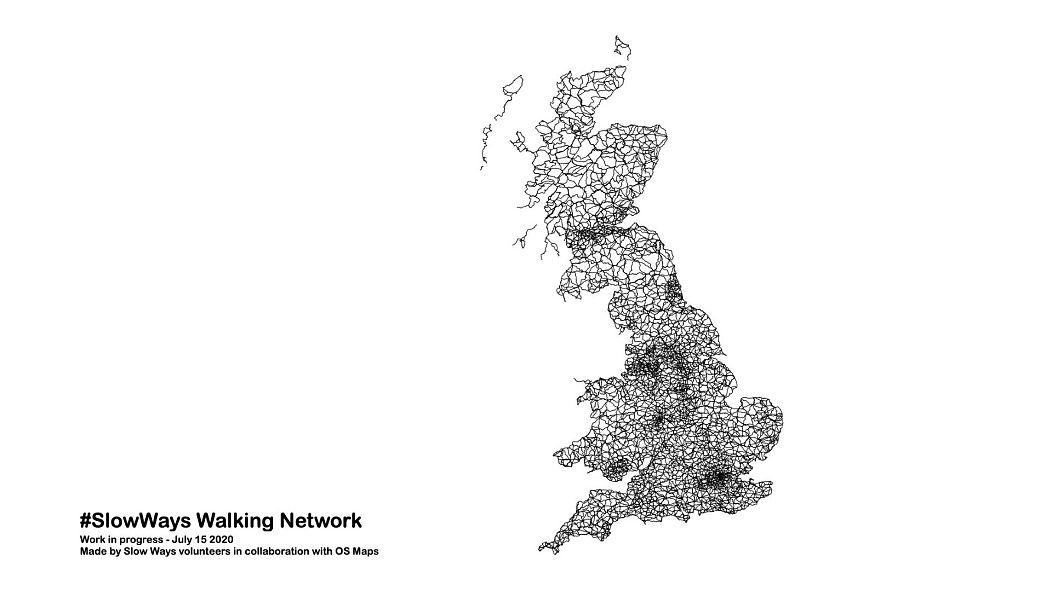

“When you look at the footpaths in the UK, although we have about 200,000 kilometres of them, that's just a big in a big mess really,” Daniel tells me. “The way I describe it is it’s almost like there’s a big pile of spaghetti.”

The UK already has a countrywide network of paths but planning a practical journey from one place to another is not an easy task. Rural routes which start and finish in the middle of nowhere can feel inaccessible for a vast majority of people and places to stay on popular walks are often prohibitively expensive.

While walking between Salisbury and Winchester, an idea struck Daniel which he believed could encourage more people to see the benefits of travelling on foot.

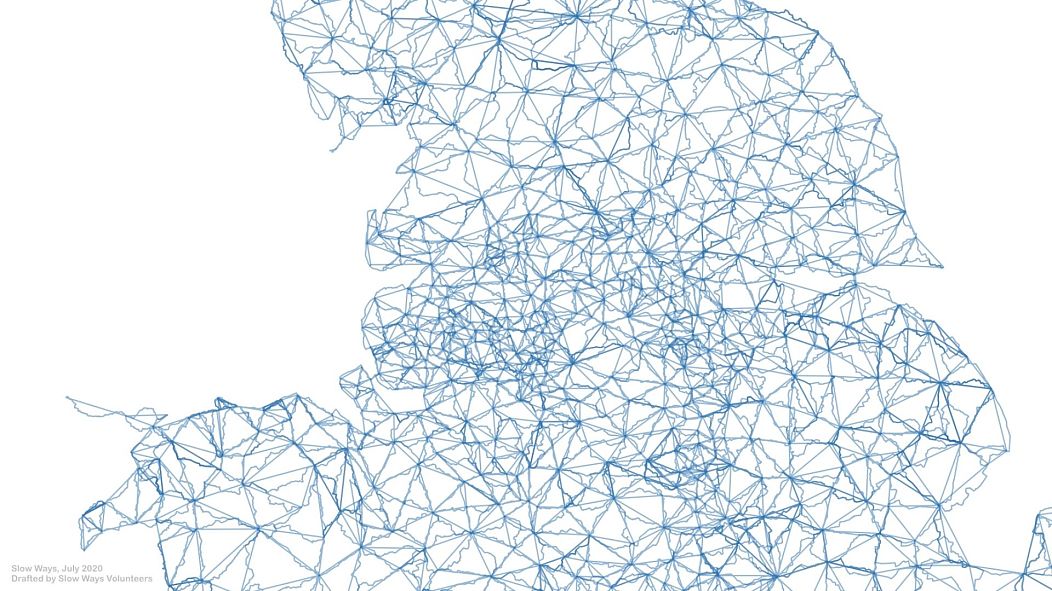

“I started to think, what if we were to create a network of 7000 routes connecting two and a half thousand places that would make it easier for people to imagine, plan and navigate.”

Getting in touch with history

In a lot of ways, the project is refocusing on why the UK’s network of footpaths originally came to exist.

“The reason why we originally have these footpaths connecting villages, towns and cities is because people just needed to get to the next village or town to trade or to see friends and family or for work,” explains Daniel.

Some routes we still use today were established as early as 5,000 BC to travel between settlements. Others were built by the Romans to move men and supplies around the country. In more recent years, many of these have turned into roads and we’d rather zip between places in our cars.

“Somehow, over those distances and maybe 5, 10, or 20 kilometres, we've lost that tradition.”

While we might decide to spend an afternoon walking somewhere for fun or as exercise, Daniel adds, we’re unlikely to think of walking as a practical way of getting where we need to go.

“I'm not thinking that people who are, like, selling bathtubs, and who drive around the country are suddenly going to start walking from Milton Keynes to Newcastle to do that,” he laughs.

“But are there some students or some people who are retired or who have the time, who might like to save themselves some money and have a life-affirming, life-changing experience by walking that same journey instead?

“Of course, it's thousands of people in that situation.”

An unexpected detour

The project was originally meant to involve getting together hundreds of volunteers across the country. Earlier this year, their plan was to walk different routes in “hackathons” throughout the summer, plotting them along the way for the network.

Just as they completed the first of these events, COVID-19, as with most things this year, got in the way. It didn’t deter Daniel, however, and he took the project online instead.

“We put out some calls on social media and literally used giant Google spreadsheets, and OS (Ordnance Survey) maps and Zoom to collaborate with 700 people who were stuck in living rooms, stuck in bedrooms, on their own in flats, people who were retired, are furloughed, and recent graduates,” he explains.

“My estimate is that about a year’s worth of volunteering took place in about a month to create these 100,000km of routes.”

Eventually, after a team of 10,000 more volunteers have had a chance to test out the extensive paths they have plotted from home, the entire Slow Ways network will be published online.

You’ll be able to search the database created by these volunteers to put together sections of footpaths between towns and cities or even daisy chain them for longer routes that cover more distance.

“You could plot that on a map. Google could give you a readout or an algorithm could give you an idea of what to do,” Daniel says, “but the fact that other people have been there before you and said you know what, this is a really direct, beautiful, enjoyable route, will mean people can start to see these really interesting other parts of the country emerge they wouldn't have otherwise thought of going to.”

Whats the slow way from London to New York?

The idea behind the project doesn’t necessarily end with walking for Daniel. Inspired by Greta Thunberg’s boat trip across the Atlantic Ocean, he has started to think about how Slow Ways could transform our travel across longer distances.

“For me the moment if I needed to go do some work in the US, I wouldn't know where to begin to think about what would be the slow way to complete that journey,” he tells me.

“I'm interested in the way that slow ways- at the moment it’s about walking great, but what if we also then thought about; how do you get across seas in the same way in the same spirit? And how do you get the sailboat so how do you kayak or how do you do those things?”

Daniel isn’t alone. Movements have been gathering across Europe and the rest of the world as people start to reconsider whether they really need to fly.

It might seem a daunting prospect and he admits that Greta’s journey looked like a particularly gnarly ordeal, but unless we start to consider these journeys as a possibility things are unlikely to change. What if it was easier to cross oceans or continents without getting on a plane, Daniel asks.

He suggests that aviation companies could even subsidise slower travel to offset their carbon footprint and make it the cheapest way to go. It would certainly appeal to those who are time rich and money poor, and perhaps even help to start eroding the idea that the fastest way to get somewhere is always the best.

Daniel believes that this year is the perfect time to be positive about relatively small, local environmental ideas growing into something bigger.

“With change and with ecological emergency and with a health crisis, we need to have desire lines to what we imagine is possible,” he says, “and then we need to try and make that happen.”