I meet Alex Fisher, who lived in a tree for a year in the 1990s to stop British forests being cut down.

“Every time I have a bath, still now, I say thank you. I still feel the gratitude. Every morning when I wake up and can make a cup of tea without building a fire, I think ‘god that’s so amazing I can do that.’”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

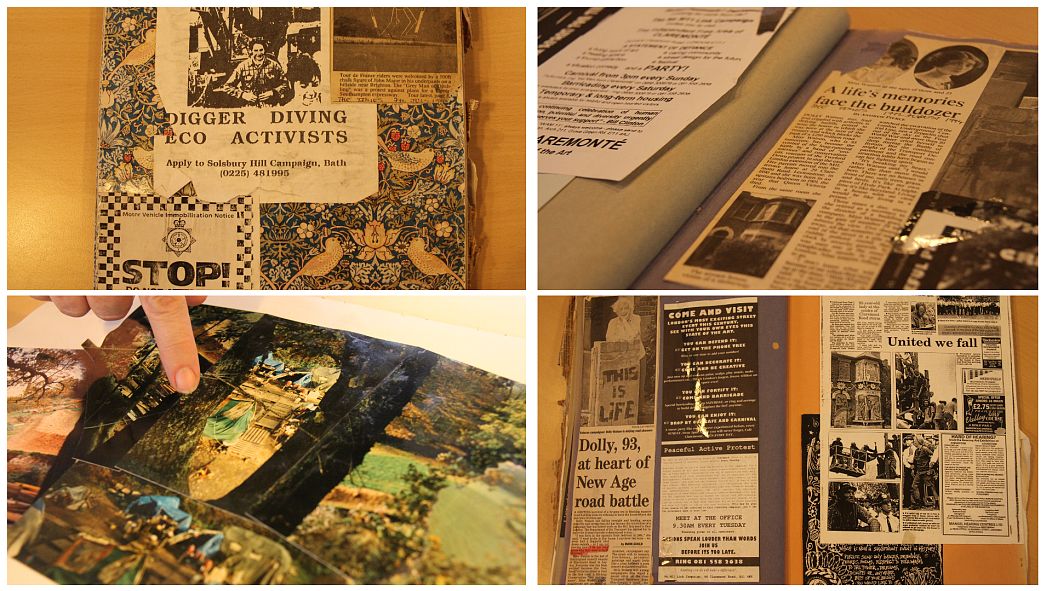

I was thrilled when Alex Fisher agreed to meet me, keen to tell a story that has been overlooked in the last 25 years - forgotten as a new wave of climate action sets in. Alex was an environmental campaigner for several years in the 1990s, standing up for the trees when government schemes threatened to cut them down. For a whole year, she lived outside in the forest, often high up in treehouses or ‘twigloos’, abseiling down tree trunks in the morning for breakfast. Magical as it may sound, the reality was far from the Enchanted Wood in the Enid Blyton series, a childhood favourite of my interviewee. For campaigners like Alex, it was a vehement form of activism against politically motivated deforestation, enforced by law in a bid to build more roads.

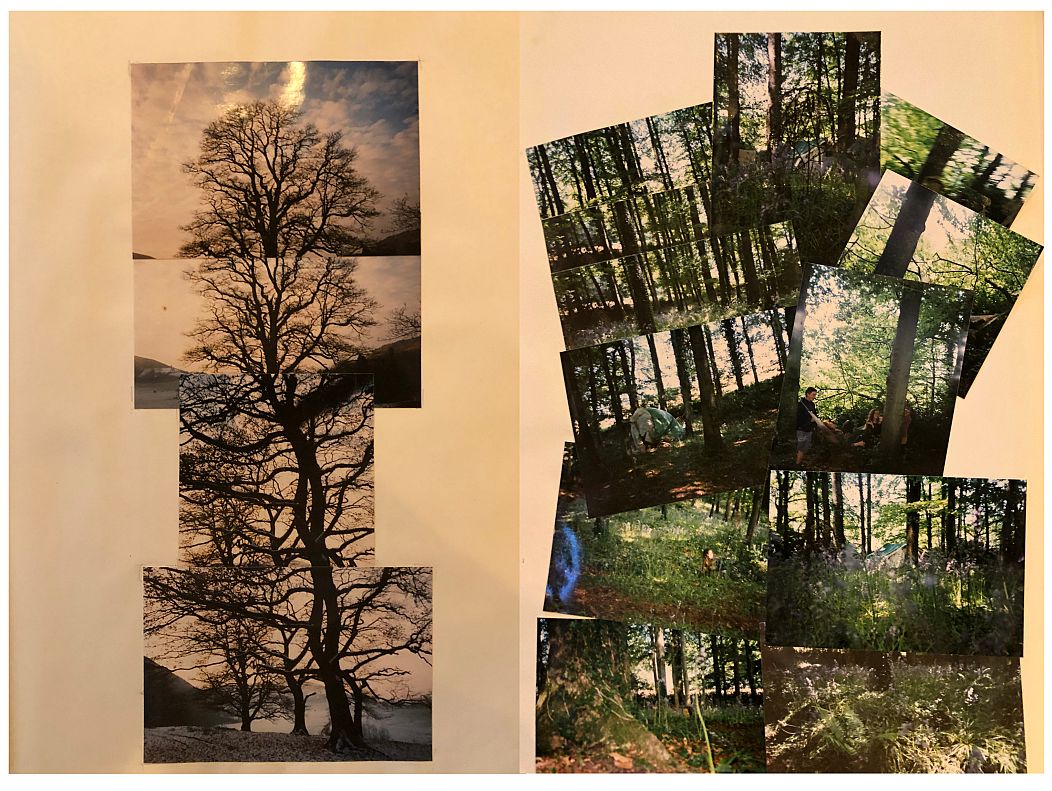

“£20 billion was the budget”, she recalls. “They called it the biggest road building scheme since the Romans.” For the activists, the problem wasn’t only the size of the project, but the places they had chosen to build the roads. Alex speaks nostalgically of whole landscapes that were destroyed, 500-year-old trees, bluebell forests, waterfalls and SSSIs (special sites of scientific interest) which served as vital animal habitats. “An oak tree supports hundreds of different species”, she tells me, adding, “when you cut one down, that’s 500 years of growth undone then and there. I planted 10 saplings from an oak tree 25 years ago, but they aren’t even old enough yet to make acorns – it takes 30 years.”

From fashion to the forest

For Alex, a deep love and respect for nature developed early on. Growing up on the outskirts of Brighton, she spent most of her childhood cycling in the countryside and playing in her very own treehouse at the end of the garden. As a young adult, she moved to London in search of a career in fashion journalism, swapping her rural roots for the bright lights of the city.

She ended up working at Vogue and, while her time there was “unbelievably exciting”, she soon realised that the fashion industry simply existed to promote what she calls “obsolete consumerism.” “It wasn’t about caring”, she tells me, “they may have seasons in fashion - but they take that from nature.” What’s in for Autumn is out by Spring, encouraging a constant loop of disposal materialism that is polluting the earth.

“I took some time out after starting my career to think about what I cared about most. We were on course to destruct the planet and when I heard about the road protest movement, I knew I had to go and take part – it wasn’t enough just to talk about it. I needed to act, and I was willing to risk my life in the process.”

Leaving London with a friend, Alex set up camp for the year at the Fairmile protest site in Devon. She speaks fondly of how quickly she adapted to living outside. “I remember waking up in the morning, making the fire and get everyone ‘breakfasted’.” She describes the resourceful ways they would have to adapt to weather conditions like snow.

What daily life was like living outside

“Often the water butt would have frozen overnight and I would literally have to gather up the snow and melt it to try and make people a cup of tea.” Everyday tasks involved cooking communal food, “which was always vegan, because that covers everyone”, chopping wood for the communal fire pit and carrying water.

“We all lived in dome-shaped benders in the trees, made from willow poles. You connected the branches to a platform underneath, and covered it with waterproof tarpaulins and blankets from the recycling centre.” Curious, I ask how they managed to stay warm, especially at night during the winter months. “Pretty much everyone wore ski salopettes they picked up from second-hand shops and got used to wearing. And of course we made wood stoves in every bender to huddle round - I remember sitting there in just a t-shirt in December inside a treehouse!”

The harsh reality

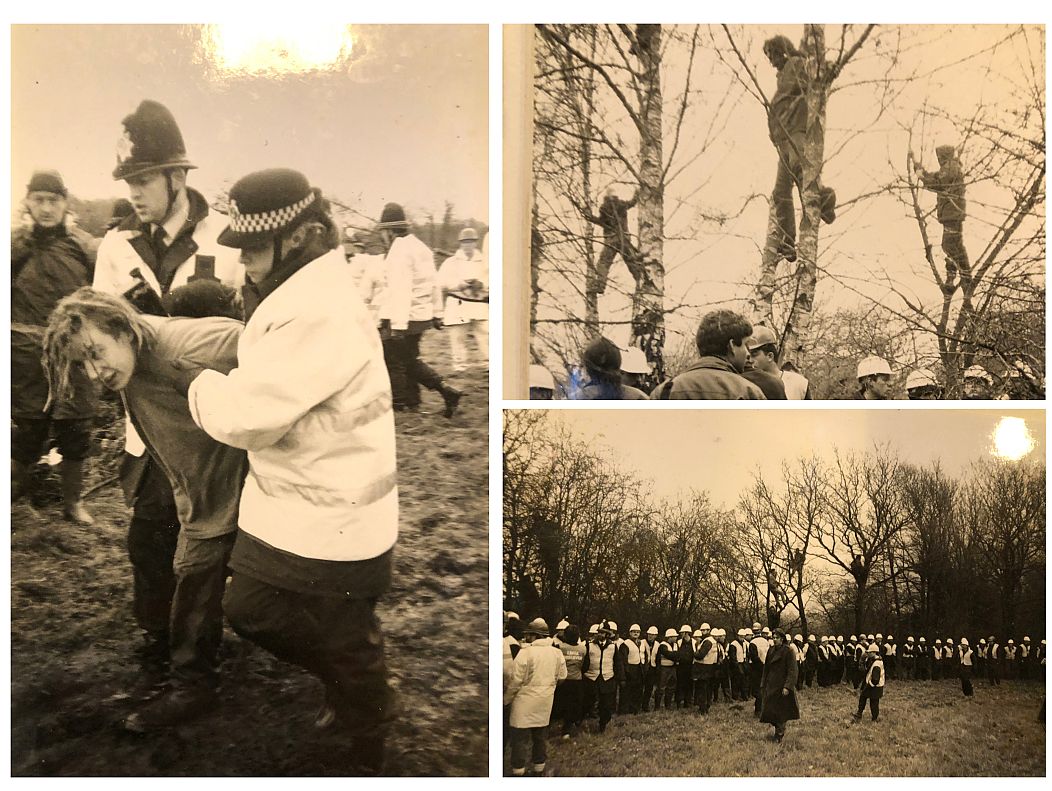

But it wasn’t always so twee. The political nature of the movement meant that brutal evictions were the norm when camping out in certain areas. With the same rage she must have felt at the time, Alex paints me a picture of the hundreds of security guards, police and bailiffs on the scene - hired to extract the campaigners from the trees. “There were threats of sexual violence by the male security, we were fire bombed, it was extremely dangerous”, she recollects.

“The security guards seemed completely unregulated. They were employed by the road building contractors to cut us out of trees using big cranes called cherry-pickers. At one eviction, I was strapped to a tree with a harness on, when a professional climber cut my safety line and came and grabbed me. I was scared for my life.”

That time she was arrested, she admits. Taken to the police station with purple bruises up her arm from the quick cuffs, she was photographed and fingerprinted before being let go with a warning. In many ways, Alex recalls she was one of the lucky ones. “I remember one person fell out of a tree and ended up in a wheelchair.” She describes the enduring trauma from that period in their lives, the sound of chainsaws haunting them for years after the protest ended.

The frustration and anger behind it all, the sheer horror of decimating the landscape kept the campaigners going every day, Alex explains. “Building more roads seemed a strange policy to adopt when the environmental issues were so well known”, she says. “They should have been investing in the railways and in cycling routes. There seemed complete disregard for anywhere that was environmentally protected.”

The magic of the trees

Nonetheless, a profound sense of community and joy appeared to encompass the movement wherever she went. “There was so much beauty and joy, it was the subtle things”, Alex laments. “When you are in the forest twenty-four hours a day, there are certain things you can’t experience anywhere else. Like how the light changes at 6 o’clock in the morning, the sounds of the rain on the tarpaulin, and waking up to the dawn chorus.”

Spending much of her time swimming and washing in the rivers, she remembers that magical feeling when, “all of a sudden, a flock of swans would just glide past you.” Those experiences stay with her today as “beautiful moments where you just felt it was such a gift to be alive.”

Speaking to this brave, humble woman, who has never expected any recognition for the fight she fought in defence of our trees, I get the impression that it was an immensely positive time in her life. Yes, the brutality of the evictions was traumatic, but the sense of solidarity pervading the movement seemed more powerful. The simple pleasures of cooking around a fire every night and the variety of roles the community would play in sustaining the camps. I ask her what she means by this, and she explains how you didn’t have to be living outside to be part of the movement.

“At one of the most high-profile camps in Newbury, everyday people would come out of their houses and say - who wants a bath? You would see 70 campaigners graciously accepting, queuing up outside someone’s house to have a bath.” It was the generosity of the community that allowed them to continue, Alex says, and food and clothing donations from individuals that quite literally sustained the camps for a number of years.

How does climate action compare today?

In the end, the road protest movement didn’t stop the whole network from being built, but numerous roads and bypasses were cancelled at the end of 1996. Activists did manage to save a lot of landscape, which “feels like a success”, Alex recalls with a sad smile. “We increased awareness. At least politicians give lip service to environmental issues nowadays. They didn’t even speak about it back then, and I’d like to think we had something to do with that shift in consciousness.”

When I bring her back to the present moment and ask what she thinks about the climate movement today, she seems frustrated. “It’s sad because everything has got so much worse than it was 25 years ago, the glaciers are melting faster than ever, we’ve already lost so much wildlife.”

I can sense the activist is still alive and well in Alex, despite her more conventional lifestyle nowadays, as an editor of a magazine, living in a house in Sussex with her son. But all hope is not lost. “Greta Thunberg has been an amazing catalyst for the younger generation”, she says. “The situation may be worse but the awareness has broadened. Extinction Rebellion have mobilised so many people – back then we were called ‘crusties’, treated as mad members of society and ostracised.”

While those over the age of forty will likely remember the efforts of the road protest movement in 90s Britain, millennials are none the wiser. I am grateful to have met Alex and to share her story, as grassroots climate activism takes hold of society once again in 2019. A “second wave”, Alex suggests. Having learnt how to be self-sufficient, she’ll never take for granted the resources that nature can provide and often longs for the days when she relied on the simple warmth of an open fire.