Our exclusive interview with conservation photographer Esther Horvath.

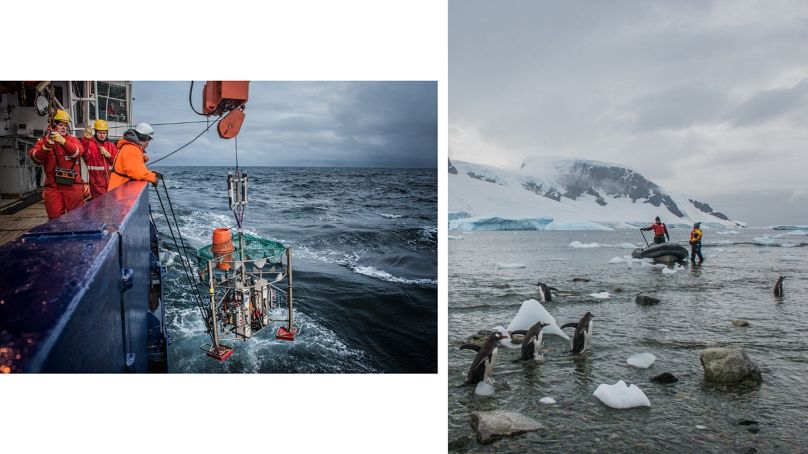

Esther Horvath is a fellow of the International League of Conservation Photographers and has recently received a fellowship from the Explorer’s Club for her work documenting scientific research in the Polar Regions focusing on climate change. She is a photographer and photo editor for the Alfred Wegener Institute, which is leading the MOSAiC project and the IceBird project. Throughout her career she has not only helped to document the important scientific research being undertaken in the polar regions, but has also focused on giving it a human face - showing what life is like for those working in these remote and extreme places. We caught up with Esther to find out what it is like being in these environments and why it is so important to document the research being done there.

Tell us a little bit about what you’re currently working on?

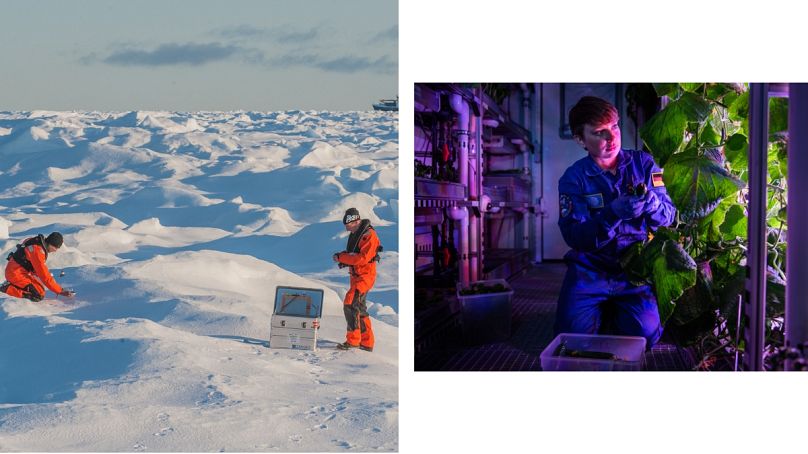

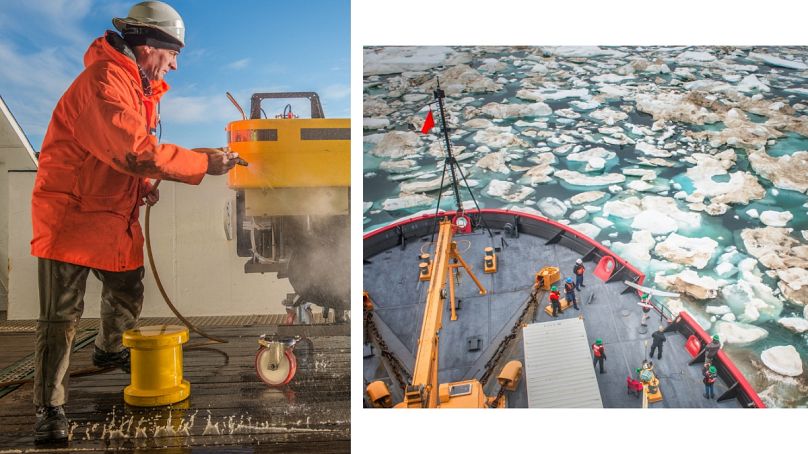

“I’ve just returned from the Arctic, where I was in Svalbard with the Alfred Wegener Institute. They were there for science and survival training to prepare for MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate), which is going to be the largest ocean science expedition in history. It starts in September when the German research icebreaker Polastern will be frozen for an entire year in the Arctic Ocean and will drift with the sea ice starting in the Siberian Shelf Seas, through the central Arctic to the Fram Strait.”

So you’ll be away for a whole year?

“I will do two parts of the expedition. The entire year is shared into six legs. With getting to the boat and coming off the boat all together one trip lasts about three months. I will be doing two trips, one from the beginning, when we embark on the 1 September. The first one is actually going to be the longest. We don’t know exactly when we’re going to return but it’ll be some time around New Year’s Eve - it’s a big question if we’re going to still be on the boat for this or already in Norway.”

So you might be celebrating on a ship?

“Yes and we will definitely be celebrating Christmas. I’ve never spent the holidays away from my family, so this will be a new experience. I focused more on the Arctic and the expeditions and scientific works are usually between March to September, because later it’s completely dark and impossible to get to a lot of places. I’ve never experienced being away at Christmas, but I’m honestly looking really forward to it.”

Why were you in the Antarctic in January?

“I was there for three weeks at the Neumayer station documenting the scientists’ lives. I follow scientific work in the Polar Regions but I’m also very interested in how people live in remote locations - what they do and how they spend their leisure time. So besides documenting scientific research I like to document life too.”

What does this involve?

“It’s very interesting, as its simple things. The crew spends 14 months at the station and so it’s little things like how you get your haircut, for example, as there are no hair stylists. Each year in each group there are nine crew members that stay for the 14 months and one crew member is responsible for cutting hair. I find things like this funny and sweet. I find it interesting how they deal with these daily problems and issues within the team.”

So you like to show the human element to these expeditions?

“That’s one of my focuses because we all know that there are changes in the Polar Regions, for example, with my work I focus on the Arctic Ocean and we all know this ice is melting, but who are the scientists that deliver us this important information? With my work, I really want to focus on the scientists and their scientific work, and give a face to those who provide us with the most important information in our natural history.”

What’s the IceBird campaign and how have you been involved?

“A team of scientists have been measuring sea ice thickness for 17 years now and I’ve been documenting their scientific findings since 2016. I’ve done four airplane based campaigns with them. The Alfred Wegener Institute is the only institute in the world which does these types of survey - this type of scientific research.”

“The scientists fly over the Arctic Ocean with electromagnetic instruments which can measure the exact ice thickness. This information is so important because it’s easy to get information about the extent of sea ice, as in how big the surface area is, but it’s very difficult to get information on the thickness. NASA has a similar project called IceBridge, which uses satellites, but they only have calculations about sea ice thickness. The team I’m following has exact measurements because when they fly over the ice they can find the exact thickness.”

“Sea ice melts from its thickness much quicker than from its extent. For example, a lake will freeze quite fast on the surface. You can see it’s frozen but you’re not able to step on. Over time it reaches a certain thickness. When it melts it reduces in thickness but again you don’t really see the changes. It might seem like the entire lake is still frozen but it might have lost half of the ice volume. It's very important to understand how the Arctic ocean is changing and how it melts, and for this we have to understand sea ice thickness. The scientists I’m following have found through their research that the sea ice thickness in the surveyed areas has decreased by 30% in 17 years.

What are the knock on effects of this?

“It will have a large impact on weather patterns and climate change. The more sea ice melts the more open water there is, which accelerates the process as the dark surface of the ocean absorbs more sunlight and increases sea temperatures, which melts more sea ice from below.”

How did you become involved with this project?

“In 2015 I got an assignment from Audobon Magazine to do a documentary on the Arctic Ocean aboard the US Coast Guard icebreaker Healy. I spent two weeks on the icebreaker

documenting research. During this time I completely fell in love with the environment and learnt a lot from scientists about sea ice. It was also interesting to see the changes during this two week period. We started at a certain location and after sailing for about 10 days and returning to the same spot where previously there was ice everywhere there was nothing, just open ocean. It was incredible to see how fast sea ice can melt. During this time I decided I wanted to focus my documentary work on scientific research in the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic Ocean became the biggest love in my life, and something so important to me, and I feel so connected to this environment.”

Why do you think it’s important for photographers like yourself to document this research?

“I feel it’s very important to document an environment that is disappearing before our eyes. In 20 years, the Arctic Ocean in summer time will be ice free. It is a very important time to discuss this, and to document the changes to this beautiful environment to highlight these changes. I feel it is my point of view and my interest to show the work of the scientists and prove these claims and show the serious projects. I want to tell the story through the science.”

“It’s a very sad story. My biggest hope is to inform politicians, decision makers and the general public as I truly hope this can bring about positive change.”

Words: Danny McCance