It's 29th February - a date that comes only every 4 years. But why, and what are the traditions and superstitions in Europe surrounding this special day?

Whether you like it or not, 2024 is a leap year, meaning today is not the start of a new month.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

For those amongst you who need a cheeky refresher as to why February gets an extra day today, leap years take place every four years.

The reason we have leap years is because the Earth’s orbit isn’t exactly 365 days long, resulting in what's known as 'drift'.

It actually takes approximately 365.2422 days for our planet to complete one revolution around the sun. That means each typical 365-day year ends a quarter-day short of the complete orbit. Therefore, leap years essentially ensure that our calendars align with the Earth’s orbit and line up with equinoxes and solstices.

If you were aware of this, what you may not know is that there are a tonne of European superstitions and traditions surrounding the 29 February – mostly linked with love and bad luck.

Here is a quick breakdown of Europe’s superstitions around the 29 February.

Greece: Don’t do it!

In Greek folklore, the superstition goes that getting engaged or married during a leap year will curse the union, and ultimately end in divorce or the untimely death of your partner. Nice and cheery to start with. As if that wasn’t enough, tradition dictates that those getting divorced in a leap year won’t find happiness for the rest of their lives.

Ireland: Ladies’ Privilege

Going against the Greek and Ukranian model is the Irish custom, which states that women can propose to men on a leap year. This dates back to the 5th century, when Saint Brigid of Kildare, who thought that women had to wait too long for a proposal, agreed with Saint Patrick that women could propose. From then on, every four years, women were encouraged to get down on one knee and ask their partner to marry them. This is known as Ladies' Privilege, and the 29th is also known as Bachelor’s Day, a day which could prove costly. Indeed, if the proposal is refused, it is tradition for the woman to receive a gift of compensation - usually a silk gown.

Scotland: Historical fines

Irish monks took the Ladies' Privilege tradition to Scotland, with an added detail: women must wear a red petticoat when proposing. It was then made law by Queen Margaret of Scotland in 1288 that any Leap Day refusal also demanded compensation: a monetary fine or, like in Ireland, the gift of a silk dress.

Denmark: No love, then glove

Same deal as the Irish and Scots, but if Danish men refuse a woman’s proposal, they have to gift the woman 12 pairs of gloves to cover up the fact that she isn’t wearing an engagement ring.

Germany: A cold year

Some Germans believe that the entirety of the leap year is unlucky. Spoilsports. Their saying goes: "Schaltjahr gleich Kaltjahr”, meaning “Leap year means a cold year.” However, later in the year, in the German state of Rhineland, there's a tradition that on the eve of the 1 May, men decorate birch trees with paper ribbons as a sign they love their partners. This is reversed on a leap year, with women invited to do the same.

Scotland (Again): Justice for Leaplings

Anyone born on 29 February is said to be unlucky in Scottish culture, and referred to as “Leaplings.” True, they don’t get to celebrate many birthdays, but to make things worse, Scottish tradition adds on another layer by saying that leaplings are doomed to a lifetime of “untold suffering.” They also consider leap years as doomed for farmers, as the saying goes: “Leap year was never a good sheep year.”

Italy: A whaley good time

In Reggio Emilia, a province in northern Italy, a leap year is commonly known as “l’ann d’la baleina” - or “the whale’s year”. The belief behind this is that whales only give birth during leap years. Whale done.

England: Bottoms up!

In 1928, Harry Craddock was working as a bartender at the renowned Savoy Hotel in London. The story goes that he devised a drink to celebrate the leap year. The ingredients included gin, sweet vermouth, lemon juice, and Grand Marnier. So, basically, it’s an excuse to get smashed on your extra day of February. Trust the English...

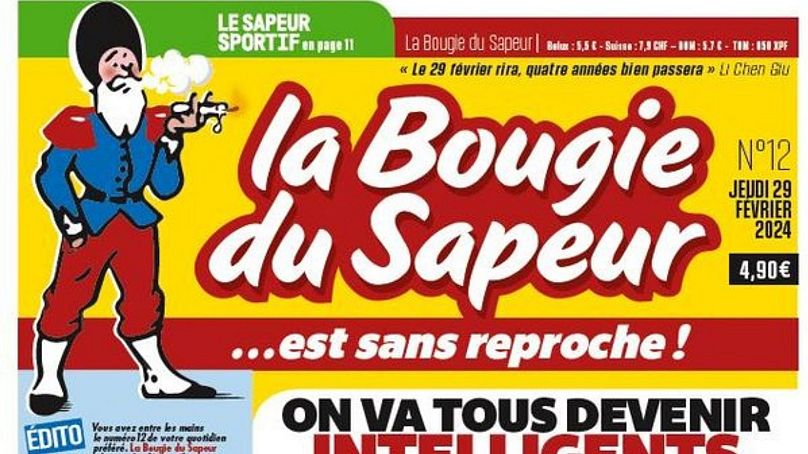

France: A unique newspaper

In France, there's a special satirical newspaper that comes out every four years on 29 February. Titled La Bougie du Sapeur, it has been running since 1980 and remains extremely popular. In fact, it usually sells out and outsells the other national papers. It became so popular that since 2016, La Bougie du Sapeur has also been sold in Belgium, Switzerland, Luxembourg and Canada. Translating to ‘The Sapper’s Candle’, the newspaper derives from a French comic book character created by George Colomb in 1896 called Camember. An army soldier (or ‘sapper’), Camember was born on 29 February and joined the army when he had celebrated his birthday four times. So, if ever you get your hands on a copy – the 12th edition comes out today - these bad boys are collectors' items – and also a fun read.