The piece, called “As Slow As Possible” by the late US composer John Cage, won’t finish until the year 2640. The next chord change is in 2 years.

When something happens exceedingly rarely, we often say “once in a blue moon.” But we might as well say “once in a chord change on John Cage’s Organ2/ASLSP”.

Sure, it’s wordy. Maybe that’s why it never stuck.

But one thing’s for sure – the musical composition, which began playing in an ancient church in Germany, is played so slowly that any minor chord change, which takes place, well, once in a blue moon, becomes international news.

That’s what happened yesterday (Monday 5 February), when a new note began playing in the piece – the first change that’s happened in two years.

Here’s what it looked like the last time a major change happened – after 7 years of the same notes playing. Crowds packed into the small church to witness the chord change, some purchasing tickets years in advance.

The tidal wave of attention is a blip on the radar for a performance that’s already been playing for 21 years and is meant to continue for another 616 years.

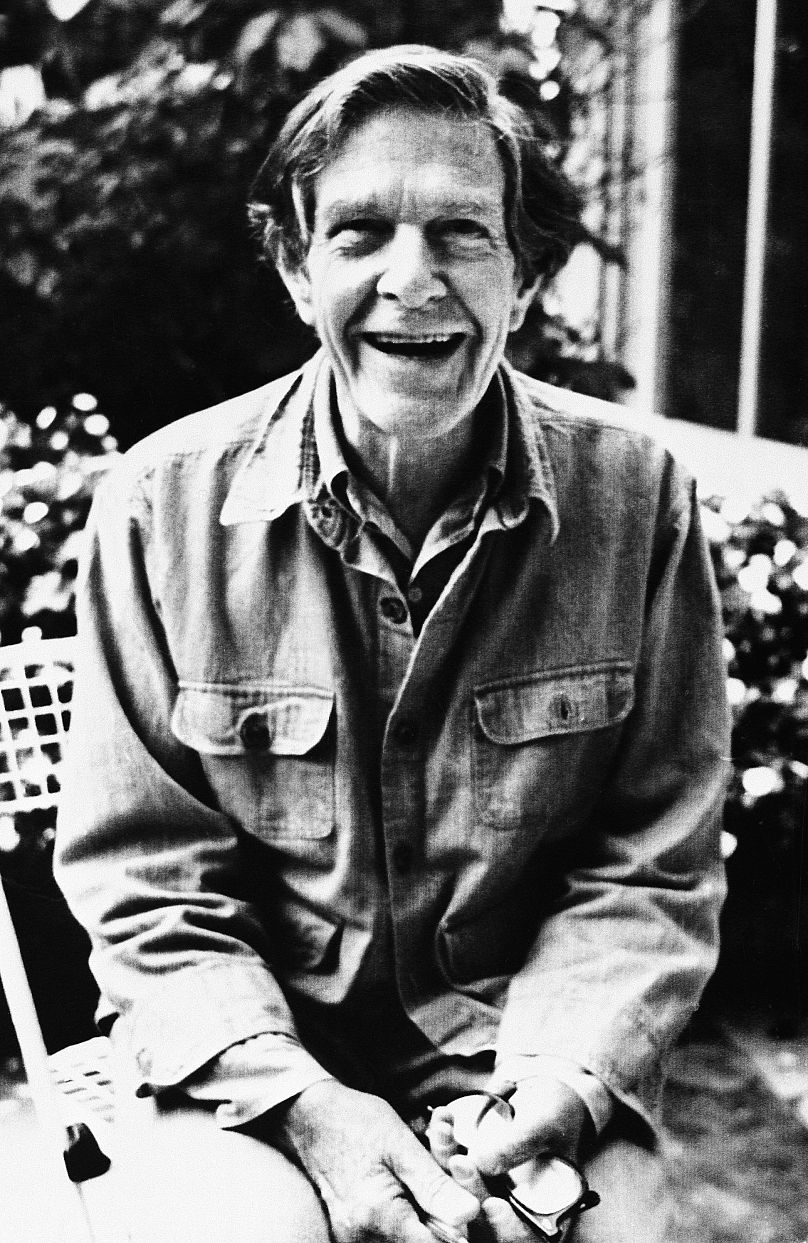

Originally written for piano in 1985, Cage adapted the piece in an arrangement for organ before he died in 1992. The experimental US composer never specified how long the piece should be played, leaving a single cryptic note: “ASLSP,” meaning “as slowly and softly as possible.”

Most of its performances have lasted between 20 and 70 minutes, but in 2001 the John Cage Organ Foundation in Halberstadt, Germany decided to take things further, agreeing that 639 years was a reasonable amount of time to honour Cage’s wishes.

The number is historically significant for the small German town – it represents the number of years passed from the construction of the world’s first 12-tone gothic organ in Halberstadt (1361) to the new millennium.

Technical considerations

So how can a piece be played for more than half a millennium? It would be impossible to expect a musician to hold down the keys for that long, so the team in Halberstadt decided to use small sandbags to keep the sound going.

The instrument does the rest – organs can sustain sound indefinitely. This particular organ has been fitted with just enough pipes to play the keys needed for the composition. An electronic wind machine keeps the air flowing.

As for playing the piece, the first part was easy – the composition begins with a short pause, which when adjusted for the new marathon duration, meant 17 months of silence.

To date, only a handful of notes have been played in the 8-page piece.

Continuing a provocative musical legacy

If anyone could appreciate the experimental 639-year organ project, it would probably be John Cage.

The US composer was known for pushing the boundaries of his art way past what audiences were comfortable with. His most famous piece is called “4’33”” – it instructs performers to sit silently at their instrument for 4 minutes and 33 seconds.

The piece continues to confound and enrage audiences who aren’t familiar with it. Some people even leave concert halls in a huff when they realise that they’ve paid to watch a musician not play.

For Cage, though, it embodied his Zen worldview, forcing audience members to be more present and really engage with the sounds around them. The piece is different every time, depending on the location, the audience, the environment.

More than anything, perhaps even music, Cage loved sounds.

“I love sounds – just as they are,” he said before his death. “And I have no need for them to be anything more than what they are. I don’t want them to be psychological. I don’t want a sound to pretend that it’s a bucket, or that it’s president, or that it’s in love with another sound. I just want it to be a sound.”

By stretching Cage’s composition to the limits of human understanding, the John Cage Organ Project is in fact decomposing the music to pure sound, creating notes that become a feature of their environment.

If anything, it’s a fitting tribute to a composer who wasn’t afraid to break down our understanding of what music can be.

The next chord change is set to take place on 5 August 2026, according to the project’s website. So be sure to mark your calendars.