On 13 June 1920, the United States banned the sending of people by parcel post after a number of instances and a previous unsuccessful attempt to outlaw the bizarre practice

It’s fairly common for a new invention to take a little while to iron out its kinks - but one of the more unusual examples of this cliche was the U.S. Post Office’s parcel service, launched in January 1913.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The new practice - which had previously only been able to deliver letters by mail - immediately widened the horizons of millions of Americans, allowing them never-before-known access to all kinds of goods and services. Not all of those services would be familiar to a modern audience, who use the post far less frequently than our predecessors.

Some seven and a half years after the parcel service began in the States, the U.S. Post Office was forced to make one serious change to its terms and conditions.

On 13 June, 1920, the body officially banned the sending of children via parcel post - yes, living, breathing children.

While parents choosing to mail their offspring didn’t become an epidemic in terms of numbers, there were enough instances to back up the prohibition of the somewhat bizarre use of the service.

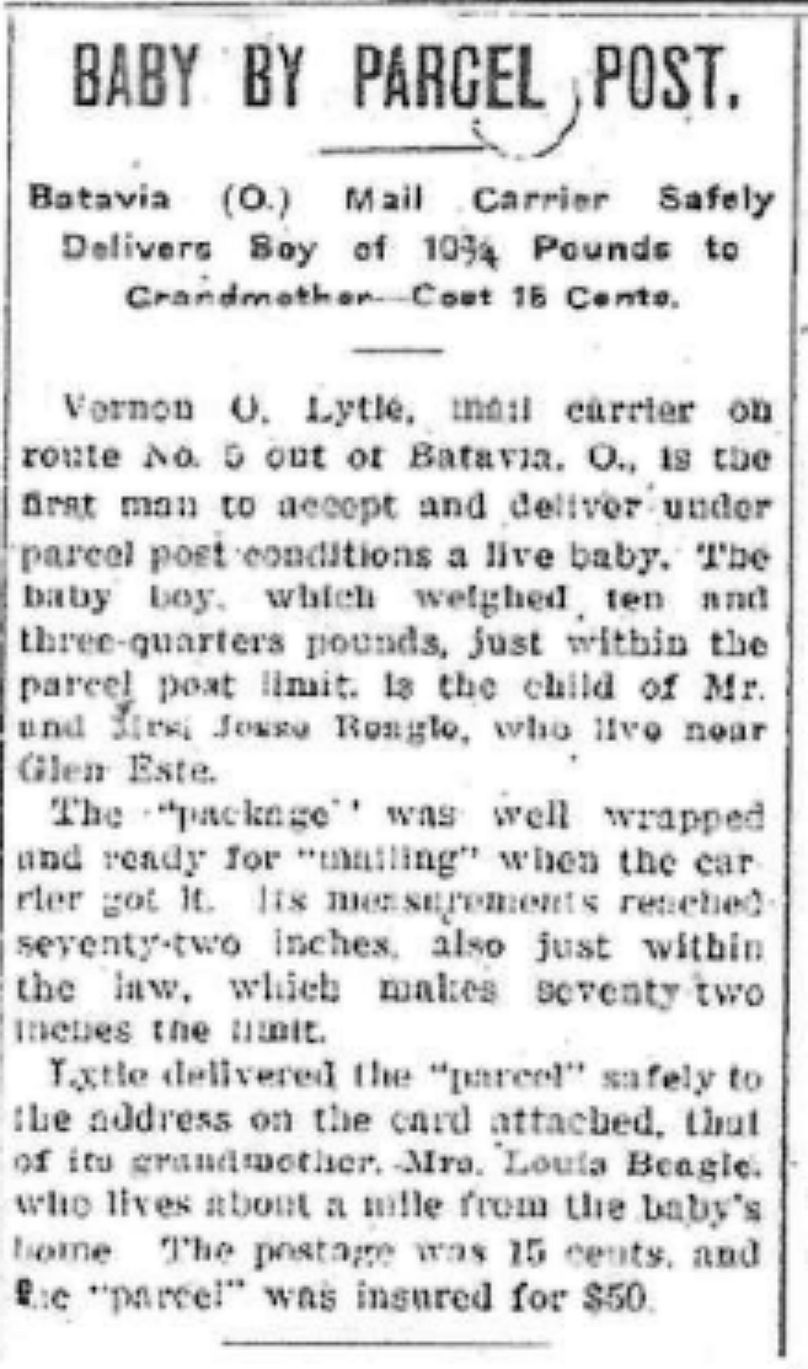

Almost as soon as the parcel post launched, in January 1913, one couple from Ohio paid 15 cents (some €4.28 today) and an unknown sum to insure their infant son James Beagle for $50 (or about €1,425 in modern terms), before handing him over to the mailman, who dropped the child off at his grandmother’s house a mere kilometre away.

Regulations were lax to say the least when post offices started accepting parcels over the weight of four lbs (1.8kg) with countless ‘unusual’ deliveries attempted, including the sending of eggs, snakes and bricks and, of course, children.

Technically there were absolutely no regulations against sending human beings and, to some, it seemed a practical way of conveniently transporting their children for a low price, regardless of obvious concerns which seem to have passed them by.

Return to sender

Representatives for the National Postal Museum, based in Washington D.C., had previously spoken about the phenomenon, explaining that the early days of the service was somewhat of a ‘wild west’ environment, with rules differing from county to county.

Nancy Pope, the late curator of history at the museum, told the Washington Post, “It was a bit of a mess. You had different towns getting away with different things, depending on how their postmaster read the regulations”.

The museum has so far confirmed at least seven instances of people posting their children before the practice was banned.

While it wasn’t very common, it was, in actual fact, cheaper to buy the stamps to send a child by Railway Mail than to buy a ticket on a traditional passenger train.

Handing over your flesh and blood to a stranger might make even the least maternal or paternal among us baulk at the very idea and, luckily, this wasn’t actually the case for the vast majority of children-by-mail.

The postman always rings twice

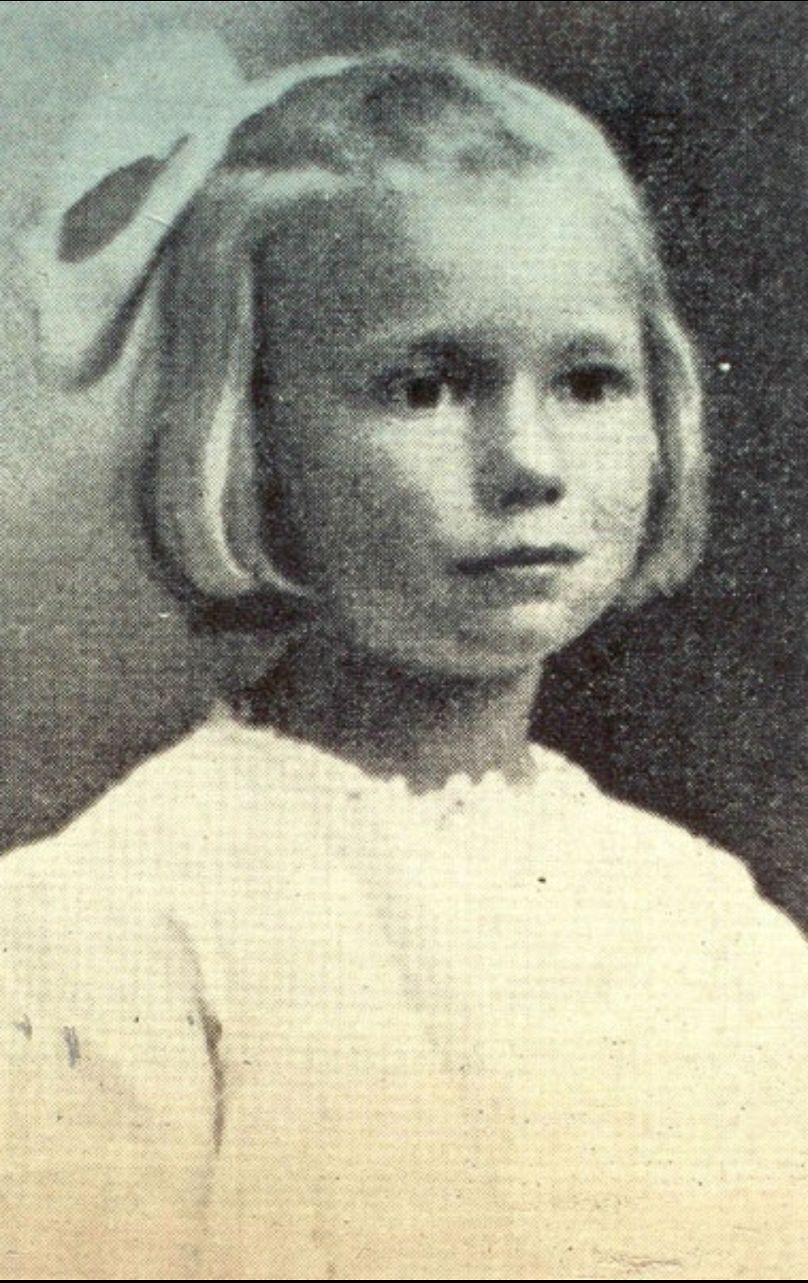

At the time, many families knew their postman quite well and, in the 1914 case of May Pierstorff, whose parents sent her to her grandparent’s house 73 miles (or 117 km) away, the postal worker who took her by Railway Mail train was actually a relative.

Regardless of the connection, Pierstorff’s parents did physically attach stamps to their five-year-old daughter’s coat, prompting the then-Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson to ban postal workers from accepting humans as mail.

A children’s book, entitled ‘Mailing May’ was published in 1997 based on her adventure, although no physical evidence of the girl’s trip survives.

The 1914 attempted ban perhaps unsurprisingly didn’t work and, just one year later, a woman in Florida mailed her six-year-old daughter to her father’s home in Virginia some 720 miles - or 1158 km - away. The journey costs just 15 cents in stamps - and is recorded as the longest ever postal trip made by a living being.

Many subsequent attempts were rejected and those that were successful saw the postmaster in charge of the mailings cautioned and questioned over the decisions to allow the transits.

On June 13, 1920, the ban eventually stuck after the then-First Assistant Postmaster General John C. Koons declared that children could not be classified as “harmless live animals”.

Jack in the box

After that announcement, parents did seemingly decide to stop sending their children via post - but, in 1980, a crafty thief, William DeLucia, took inspiration when he shipped himself in a crate via airmail.

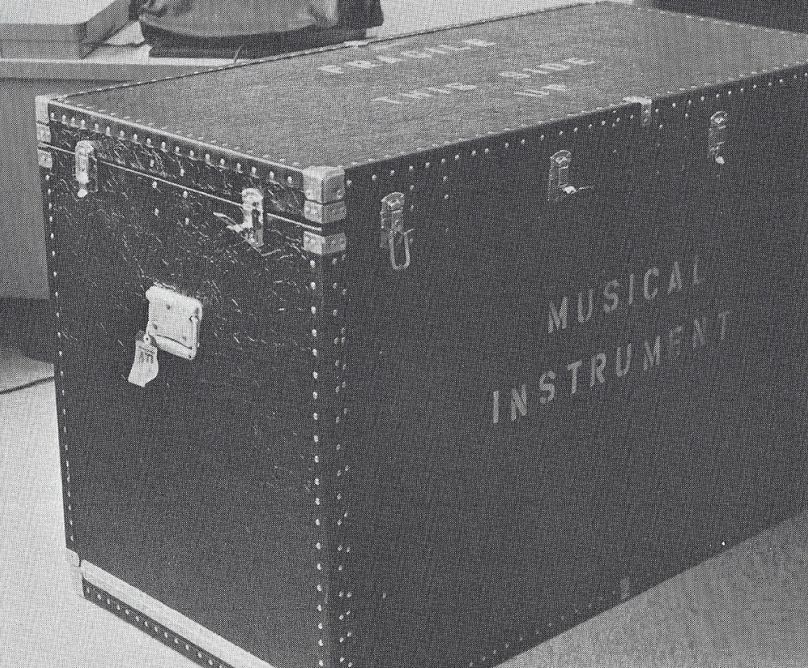

DeLucia made headlines in the so-called ‘Jack in the Box’ case, after breaking out of his crate - labelled ‘musical instruments’ - and stealing thousands of dollars worth of goods from legitimate mail also on the plane. He was arrested at Atlanta airport after his hiding place, complete with food and an oxygen tank, popped open as it was being unloaded.

The National Postal Museum is home to that very oxygen tank, but we wouldn’t recommend DeLucia’s style of crime - he was convicted of mail theft, along with his accomplices.