Euronews Culture caught up with Spanish journalist José Núñez to discuss his new book, 'Shukran my friends', chronicling his experience spending 40 days inside a Greek refugee camp in 2016.

In 2016, José Núñez, a journalist from Madrid, spent 40 days in a military-administered refugee camp in Katsikas, a town located six kilometres outside the city of Ioannina in northwestern Greece.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

The site was set up on 17 March 2016 and hosts hundreds of migrant families, mainly from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

During his time there, Núñez learnt about many of the heartbreaking stories of those displaced from their home countries and experienced the harsh living conditions inside the camp.

While he never had the intention of writing a book, upon returning home to Madrid Núñez began to write down everything he could recall from his time at the camp, in what he describes was a "catharsis" for him.

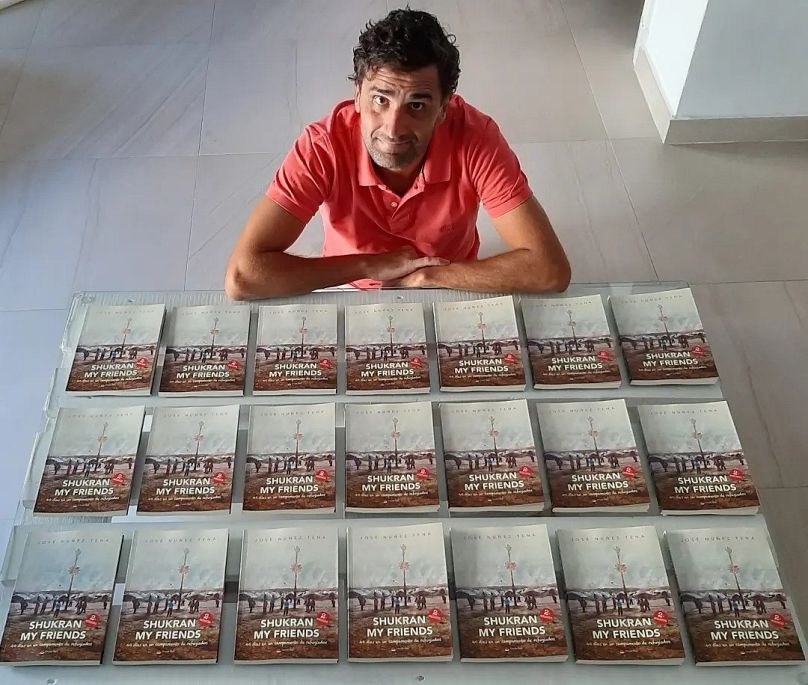

Six years on and he has now released 'Shukran my friends', a book chronicling his experiences in Katsikas and sharing the many personal accounts of the refugees he met.

The book, which was nominated for the Círculo Rojo Awards, one Spain's most prestigious literature prizes, also highlights the incredible work of the many volunteers at the camp, who Núñez describes as the book's "heroes".

Euronews Culture caught up with Núñez to learn more about his time in Katsikas and why he thought it was important to write the book.

Euronews Culture: What inspired you to write this book?

José Núñez: During my days in the refugee camp, certain things made me think: "I should write this." Later, when I went back to my ordinary life, I had a hard time remembering my days in Katsikas, and I started writing as a catharsis. So I guess it was a combination of my personal need and my desire to let people, people close to me, know what I experienced there. And that ended up turning into this little book.

How would you describe life at the camp during your time there?

I guess the word that best defines it is "desperate." Of course, it is also hard, unfair, difficult on a day-to-day basis... But personally I would say that the feeling I perceived the most was that of despair. It's not only living in such conditions, but you don't know for how long it will last. You get promises from Europe about deadlines and destinations, but time goes by and everything remains the same. It was desperate, but strangely enough, hope was never lost.

Greece has been under enormous pressure to improve facilities and the handling of migrants. Is it succeeding?

When I was there, in 2016, I couldn't believe my eyes. There were no trailers or anything like that, but only tents that were not even waterproof, so when it rained it was a disaster. The floor was made of stones, the food was provided by independent volunteers.... From what I saw, the work of the organisations in charge of running it left a lot to be desired. If it wasn't for the independent volunteers, I don't know what would have happened to those people. Of course the situation has improved somewhat, but during those days you felt ashamed to be European.

What kind of stories did people at the camp share with you about why they left their home countries?

It depended a lot on the country of origin, of course. Some were fleeing from Al Assad's bombs, others from Daesh.... They would show you videos of their homes torn down into rubble. Some children could be very explicit, and made the gesture of cutting off their heads when they told you about their country. Some told you everything as a catharsis, others preferred not to remember anything at all, just to look forward. I remember how a refugee woman told a volunteer that one day she wanted to write not the memories of her past, but of her future.

What did you personally learn from your experience?

Not to prejudge. I think 'Shukran my friends' is a kind of road movie on paper, a road book. It's a physical journey but also a personal one, full of learning, and people who are constantly opening your eyes and shutting your mouth, in a good way. At one point a refugee said to me: "My friend, I'm from Iraq, not from Mars". I think that sentence sums up the whole book.

Spain has been in the front line of the migratory crisis long before it was news all over Europe. How do you see the situation now? Are people tired of the issue or do they want to do more?

There's a bit of everything, I'm afraid, but in general I think Spain has always been an example. I know many people who are willing to help those in need, who don't come to Spain for the sake of it but out of necessity. The response with the Ukrainian refugees is a good example, although one wonders why with the Syrians or Iraqis the response was not the same. Cultural reasons? Religious? Fear of jihadism? There is a lot of misinformation regarding these points, a lot of prejudice. I first learnt about it at Katsikas.

What does the treatment of immigrants and refugees across Europe tell us about how we regard ourselves and others?

Europe has a short memory. It was not so long ago that we were the ones migrating from one country to another fleeing bombs and simply looking for a place to work and be able to live in peace. I think we take the welfare state for granted, and everything beyond our borders seems to us, as that refugee said, like Mars. And if I learned anything during my days in Katsikas, it is that tomorrow the war can reach you, and the example is Ukraine. There is a lack of empathy. And let's remember that our world is not the real one. It is, in fact, the unreal one.

'Shukran my friends' is currently only available to buy in Spain.